I’ve Got Beef with Yunte Huang. This Is My Diss Track.

setting the record straight on one scholar’s reckless claims

Summer 2024 was the summer of the diss track. Now, summer may be over, but I’ve got a diss track of my own to drop. I’ve been biting my tongue for more than a year and keeping my thoughts to myself about another biographer’s treatment of Anna May Wong. It’s time I finally speak my truth. Besides, there’s nothing wrong with a good old fashioned literary feud. (I’ll let you decide who’s Kendrick and who’s BBL Drizzy.) Stick with me, ‘cause this is going to be a looong one.

I deliberated for months on how to convey what you’re about to read—and whether to say anything at all. I spoke to my husband, close friends, trusted colleagues, and even my therapist at length. I spent many nights in bed, mind racing, wondering what I should do. I asked myself, what would Anna May Wong do? Would she keep quiet or speak out about something she knew was wrong? In the end, I realized that I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t find the courage to speak up.

Some of you may already be familiar with the name Yunte Huang. He’s the author of Daughter of the Dragon, a biography of Anna May Wong that came out in August 2023. I won’t pretend that the scholarly world of AMW is without its own internal drama. Believe me, it’s got plenty of that! But in general, I try to be cordial and open with my scholarly peers because I think there is more to gain from our collective knowledge when we can work collaboratively and celebrate each other’s discoveries. One would think we’re all after the same thing, i.e. uncovering the truth and expanding what is known about AMW.

Here’s where things get sticky and the reason I’ve got beef with Yunte Huang: He purports to be a scholar of Anna May Wong (he is a Distinguished Professor of English at University of California, Santa Barbara and a Guggenheim Fellow), except that his book is filled with outlandish, unfounded claims. The kind that would never make it into a newspaper of record like the New York Times because if his claims were fact checked, there would be nothing to substantiate them. There’s no there there.

Hidden in the pages of Daughter of the Dragon are several consequential allegations that deal with Anna May Wong’s sexuality and love life, including whether she might have been sexually abused as a teenager.

When Huang’s book came out last year, I skimmed through it. I was curious to see how he treated various moments throughout AMW’s career and whether we agreed or differed. I saw right away that there were some questionable statements and errors in his book. For example, Huang writes that Wong Sam Sing’s laundry was bulldozed in 1933 with the rest of L.A.’s Chinatown to make way for Union Station, but the laundry wasn’t located in Chinatown. Wong Sam Sing simply retired from the business (he was in his 70s). He declares that AMW’s favorite catchphrase was “and Confucius didn’t say this,” but the phrase wasn’t mentioned in any of the interviews, letters, or documents I reviewed and Huang doesn’t cite a source for this detail. These are relatively minor points, unintended mistakes perhaps. As I admitted in a recent post, biographers are fallible. We all get a few things wrong despite our best intentions.

But the closer I looked at Huang’s book, the more alarmed I became. Hidden in the pages of Daughter of the Dragon are several consequential allegations that deal with Anna May Wong’s sexuality and love life, including whether she might have been sexually abused as a teenager. And yet, Huang treats these admissions like juicy pieces of gossip, like lurid secrets he delights in revealing.

Daughter of the Dragon has some curious omissions, too. For example, Huang fails to mention AMW’s first brush with the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1924 when she was cast in The Alaskan; the cast and crew traveled to Canada for filming, but at the border it was discovered AMW didn’t have the appropriate identity papers or permission to leave the country as a Chinese American. This was a consequential episode in her personal history, which I document in Not Your China Doll.

Similarly, Huang mentions Paul Robeson only once in the book and says nothing of AMW’s friendship with him. He also leaves out known love interests like cinematographer Charles Rosher and composer Constant Lambert. Nor does he touch upon her friendships with Ramon Novarro, Harry Carr, Grace Wilcox, Emil Jannings, and many others—or the much buzzed about dinner parties she often hosted in Chinatown for her Hollywood circle. However, these are merely my complaints as a fellow biographer who sees the important beats of AMW’s life differently. They’re not ethical quandaries that rise to the same level of seriousness as the aforementioned claims about AMW’s sexuality.

For what it’s worth, Huang’s book does offer a few interesting insights. The parts I appreciated most were his references to Chinese-language source material—sources that a non-native, non-fluent researcher like me would have a difficult time tracking down on their own. (I have a working knowledge of Chinese but I’m hardly literate.) For example, he references Moon Kwan’s autobiography. Kwan was a friend of AMW’s who had worked in Hollywood as a consultant of films like Broken Blossoms before returning to China to become a director. Huang explains that Kwan taught AMW how to play the yueqin or Chinese banjo, as well as several classical Chinese poems so she could incorporate them into one of her early vaudeville acts (Daughter of the Dragon, p. 86 - all references refer to the hardcover edition). Huang also cites an account by Gongzhe Ge, a Chinese journalist traveling through Europe, who ran into Anna May and her sister Lulu at a Tientsin Restaurant, a Chinese restaurant they frequented in Berlin (Daughter of the Dragon, pp. 106-107). These interesting details enrich our knowledge of AMW.

It wasn’t until I participated in an event at the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) in New York this past spring with Yunte Huang and Graham Russell Gao Hodges, however, that I realized the gravity of Huang’s false claims. (A video replay of the event is available on YouTube in two parts: Part 1 & Part 2.)

At the end of our panel, a question was raised from one of the audience members. They asked why we thought Anna May Wong was a gay icon. This, naturally, led Hodges and Huang to a discussion of their theories that AMW was bisexual. I strongly disagree with them on this point, which I have written about in LitHub and elsewhere. No evidence beyond mere rumor and the subjective interpretation of photographs supports their claims.

Nested in his comments that evening, Huang said something that woke me up and nearly knocked me out of my chair. “In fact, [Anna May Wong] was initiated to Alla Nazimova’s 8080 Club . . . [Nazimova] was openly lesbian, the one who coined the term sewing circle . . . She was really grooming young girls, initiating them into both heterosexual relationships but also homoerotic relationships as well.” (my emphasis)

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. An alleged relationship between a teenage Anna May and the early Hollywood star Alla Nazimova was the wildest, most outrageous claim yet. Even more alarming was the fact that Huang used the word “grooming.” That’s not a word to throw around lightly. It conveys a serious allegation—that Nazimova was a pedofile who sexually abused an underage AMW. What’s more, “grooming” is often used by the alt-right as a dog whistle against the LGBTQ+ community to suggest that the mere presence of gay people in public life will have the effect of “grooming” young children to become gay. As if a person could be influenced into becoming gay, rather than being born that way.

I did my best to counter Hodges and Huang’s comments as diplomatically as possible in front of the audience at MOCA that night. But I went home feeling deeply disturbed by the things that had been said, at a recorded event no less. In August, I sent an email privately to Hodges and Huang expressing my concerns with their irresponsible claims. I have yet to receive a response from either.

As a result of that event, I realized that I needed to look at Huang’s book more closely. This time around, I read it cover to cover and fact-checked his claims with a fine-tooth comb. What I found in the pages of Daughter of the Dragon enraged me. And I’m going to lay it bare here for all to see so that you, dear reader, can make up your own mind about the evidence (or lack thereof).

False Claim #1: Alla Nazimova engaged the teenage Anna May Wong in a “homoerotic relationship”

The Alla Nazimova allegation appears early on in Huang’s book. Before I get into what he writes about it, let me give you a little context. By the age of 13, Anna May started making efforts to get herself into the movies. In the fall of 1918, the flu pandemic hit Los Angeles and schools closed, which became the perfect opportunity. James Wang, a Hollywood-Chinatown go-between, was recruiting extras for Alla Nazimova’s film The Red Lantern, a tale of dueling half-sisters set against the Boxer Rebellion in China. Wang couldn’t get enough background people because many had decided to stay home because of the pandemic, so he agreed to take the young Anna May on as one of the extras. Long story short: AMW was elevated to one of three lantern bearers in a scene with Nazimova and this became her first uncredited role. AMW retold this story many times over the years when she was asked to recount how she broke into the movies.

Here’s what Huang writes about this early episode in AMW’s career:

Nazimova was a renowned personage with a storied past and a colorful presence in Hollywood. . . . By the time The Red Lantern was in production in 1918, Nazimova had become so rich and successful that she was able to buy a sprawling Spanish-style home on three and a half acres at 8080 Sunset Boulevard . . . Dubbed the “Garden of Alla,” her stylish residence was a classic movie star’s showplace . . . The place became a popular spot for Hollywood soirees, attracting a largely lesbian following. . . . Young Anna, as we shall see, would also fall under the spell of the prima donna credited with the coinage of the term sewing circle, a discreet code for a gathering of lesbian and bisexual thespians. (Daughter of the Dragon, p. 53) (my emphasis)

Though he doesn’t come out and say it, Huang’s insinuations are clear. He suggests that through AMW’s connection to Alla Nazimova, she was inducted into lesbian social circles as a young girl. But how do we know that AMW and Nazimova ever interacted directly? AMW was one of several hundred Chinese extras on the set of The Red Lantern. It’s plausible that they might have shared a word or two, but the idea that they maintained a friendship off the set begins to stretch credulity.

A few pages later, Huang shores up his proof:

An extant photo shows fourteen-year-old Anna sitting by the pool in the Garden of Alla. . . . Even though she was one of the six hundred Chinese extras on the set of The Red Lantern, Anna’s youthful charm must have caught the eye of Nazimova, who invited the adolescent to the Garden of Alla, also known as the 8080 Club. At the movie colony’s first salon, the guests would drink, gossip, and listen to Nazimova rattling off in her linguistic trifecta of English, Russian, and French about memories of Yalta and Moscow, and her coach Stanislavsky. Maintaining the facade of marriage to a man while romantically involved with various men and women, Nazimova was openly bisexual. . . . It would be foolish, or perhaps distasteful, to speculate on the nature of young Anna’s relationship to Nazimova as anything other than that of a protégé to a mentor. . . . One day, as we shall see, Anna would enter the intimate circle of Marlene Dietrich, perhaps in the same ingenue way she neutered the 8080 Club. (Daughter of the Dragon, pp. 56-57) (my emphasis)

Huang’s proof is a photograph. But, as I’ve said before, photographs can lie. Or rather, they can be interpreted to say the thing the beholder wants them to say. So let’s take a closer look at the photograph he’s offered as evidence.

The photo does indeed look as though it was taken at the Garden of Allah; the pool was the property’s most famous feature and was often photographed. The problem is that Huang dates the photo to 1919, right around the time Nazimova would have bought the property, when AMW was just 14 years old. Nazimova later converted her home into a hotel in 1926, then sold it in 1930 and the Garden of Allah Hotel reopened under new management.

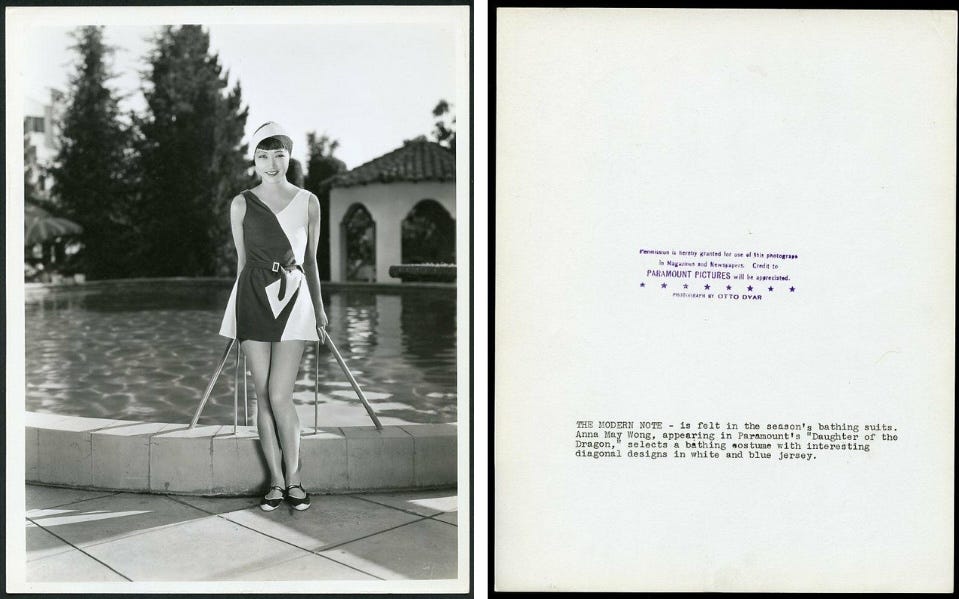

Anyone familiar with early Hollywood history and AMW’s career could tell you that this photograph was not taken in 1919. Even Getty Images, where Huang licensed the image for his book, dates the image to 1931. That’s a 12-year difference, not a small discrepancy. And though it’s marked as part of the John Springer Collection, the photo was taken by Paramount studio photographer Otto Dyar as it matches a series of photos he made of AMW from that time.

Another photo from this session was sold on WorthPoint and includes Dyar’s name, Paramount’s permission line, and the following caption:

THE MODERN NOTE - is felt in the season’s bathing suits. Anna May Wong, appearing in Paramount’s “Daughter of the Dragon,” selects a bathing costume with interesting diagonal designs in white and blue jersey.

WorthPoint also dates the photo to 1931. In fact, I included a similar portrait by Otto Dyar, one I previously cited as my favorite picture of AMW, in the front matter of my book, dated circa 1931. It’s likely from the same session since AMW is posed by the same pool in a different bathing suit.

There are a few other reasons why Huang’s selected photo couldn’t have been taken in 1919. First of all, Anna May didn’t look like that at 14, which is easy enough to tell from her appearance in Dinty, a film that came out in 1920 when she was 15. Secondly, the picture of AMW at the Garden of Allah pool is clearly a publicity still, i.e. a portrait typically made by studio photographers to promote actors and upcoming films. No studio would have been taking publicity photos of an unknown 14-year-old actress who had yet to sign her first contract.

Now, let’s just say for argument’s sake that the photo truly was taken in 1919 (and me and Getty/WorthPoint and all the other Hollywood experts are wrong about the date). The photo itself still doesn’t tie AMW to Nazimova in a “homoerotic” liaison. Nazimova isn’t in the picture and there isn’t a rager of a party going on in the background. It doesn’t look like anything more than what it is: Anna May Wong sitting by a pool so she can take a photo in a cute bathing suit.

The peculiarity of Huang’s claim really gets under my skin because it’s so far from anything that makes logical sense. How do you go from a picture of an innocent bathing beauty to Huang’s innuendo-laden line: “It would be foolish, or perhaps distasteful, to speculate on the nature of young Anna’s relationship to Nazimova as anything other than that of a protégé to a mentor.”

I had to know how he jumped to this veiled conclusion. So I did a reverse image search and this is what came up: an Alla Nazimova fan blog that dates the photo with little evidence to 1919 (and also spells AMW’s name wrong). Conveniently, Huang does not cite the blog as one of his sources.

Huang’s suggestion of an illicit sexual relationship between AMW and Nazimova or the women in her so-called sewing circle is nothing more than a sloppy game of smoke and mirrors.

False Claim #2: Anna May Wong and Marlene Dietrich were lovers

The next major issue with Huang’s book is that he repeats the myth touted by Hodges and others about a romantic or sexual relationship between AMW and Marlene Dietrich. He already hints at this in the quote about Nazimova from page 57: “One day, as we shall see, Anna would enter the intimate circle of Marlene Dietrich, perhaps in the same ingenue way she neutered the 8080 Club.”

Huang, like Hodges, cites Donald Spoto’s biography of Marlene Dietrich, Blue Angel, in which Spoto writes: “Dietrich openly discussed her casual amours, which included men from film studios with whom she spent an occasional night, actors from the theater who she thought required a little attention, and those like Anna May Wong and Tilly Losch, who were clever, amusing and exotic companions.” Spoto does not provide a citation or any proof for this statement. So Huang is just parroting rumors that have no substance.

In my own research, I came across several details that dissuaded me from these rumors. AMW had an active social life. If you were friends with her, your name was bound to turn up in Hollywood social columns alongside hers. This was the case for friends and colleagues like Ramon Novarro, Una Merkel, E. A. Dupont, James Wong Howe, and even former lovers like Charles Rosher and Marshall Neilan, who she remained friends with. Marlene and AMW’s names never come up together at social functions outside of the studio. Even in my limited research in German-language publications, their names are never connected socially. Add to that the fact that Marlene doesn’t mention Anna May in her autobiography and the strange omission of Shanghai Express from its pages, one of her best films.

Commentary from Maria Riva, Marlene’s daughter who accompanied her mother to the set of Shanghai Express at age 7, is often held up as further evidence of some sort of liaison. Riva wrote a tell-all memoir about her mother’s life that details her many love affairs with men and women. But Riva’s descriptions only discuss the two women’s professional friendship on set. And, well, if you’ve read her book you know that Marlene was exceedingly busy during the making of Shanghai Express, attending to affairs with both her director, Josef von Sternberg, and French lover Maurice Chevalier. When would she have penciled in AMW?

The final piece of evidence that laid this rumor to rest was this: I decided to ask Maria Riva herself, the one person still alive who would likely know whether Marlene ever slept with AMW. I asked her whether the rumors about her mother and AMW were true. She replied: “Absolute nonsense. Pals, yes. Lovers? No. Intimate friends in the sense they talked as young women do—especially regarding growing fascism and racism? Sure.”

If you don’t want to believe what Maria Riva has to say about her mother’s affairs, then you shouldn’t also cite her book as evidence of a Marlene/AMW hookup.

False Claim #3: Anna May Wong and Dolores del Rio were lovers

A variation on this theme is Huang’s casual mention of Dolores del Rio as another possible lover. Male biographers really do love to sling around sexual rumors, don’t they? Huang writes:

In fact, Dietrich was not alone in counting Anna May as her lesbian lover. Dolores del Rio, the Hispanic actress who would one day be immortalized next to Anna May in a public-square shrine on Hollywood Boulevard, was also said to number Wong, besides Henry Fonda and Orson Welles, among her paramours. (Daughter of the Dragon, p. 164)

This is the kind of hearsay I have often seen bandied about on spammy websites and fan blogs. Huang cites a Boston Globe article from 1990 titled “Hollywood Hotline.” The article is little more than a short promotional blurb for a new book by George Hadley Garcia called Hispanic Hollywood. “Dolores Del Rio numbered among her lovers Henry Fonda, Orson Welles and Anna May Wong,” the article declares.

The curious thing here is why Huang cites a newspaper article and not the book itself. Was it just laziness that kept him from going to the original source of this claim or something else?

I bought a used copy of Hispanic Hollywood to see for myself. There are only two mentions of Anna May Wong in the book, none of which involve her being Dolores del Rio’s lover.

Btw, Dolores del Rio also wrote the foreword to the book! So if she had something to say about AMW, she had her chance.

False Claim #4: Anna May Wong was a lesbian

Huang mentions several other points in passing to shore up his theory that Anna May Wong was a lesbian.

Following her life-changing trip to China in 1936, AMW returned to Hollywood with a new perspective on her career. She persuaded Paramount to let her play a crime-busting heroine in the vein of the successful Charlie Chan detective series and began producing a set of groundbreaking films. The first of these was Daughter of Shanghai (1937), in which she and childhood friend Philip Ahn play the heroes out to stop a human trafficking ring that tricks hopeful immigrants into indentured servitude. The film made AMW and Philip Ahn the first Asian American actors to play a leading romantic couple in the sound era.

During production on the film, Paramount and Hollywood gossip columnists tried to make hay out of AMW and Philip’s long standing friendship and planted various rumors that the two were carrying on an off-screen romance, planned to elope soon, etc. None of the rumors were true and Anna May and Philip remained friends.

Huang, however, saw this as an opportunity to elaborate on his theories:

The combined factors that Wong and Ahn were chums from high school and that Kim Lee proposes marriage to Lan Ying at the end of the film spurred the Hollywood rumor mill into wild speculations that the two Asian American actors were romantically involved, unaware that Ahn was, quite possibly, gay. . . . Being ambivalent and elusive might have been a good publicity tactic, for, in typical Hollywood fashion, unfounded gossip always creates buzz, keeping curiosity alive. But it is also possible that these two Asian American actors, living in an era when homoeroticism was taboo, were using each other as a proverbial “beard.” Especially in an industry where being “outed” as a homosexual could easily doom one’s career, there were countless examples of “lavender marriages” or “tandem couples”—Judy Garland and Vincente Minnelli, Charles Laughton and Elsa Lanchester, Laurence Olivier and Jill Esmond, Barbara Stanwyck and Robert Taylor, to name just a few. (Daughter of the Dragon, p. 258) (my emphasis)

This is an interesting idea, but again, there’s no evidence to support it. (I’m not even going to get into the validity of the so-called lavender marriages Huang lists.) It’s true that neither AMW nor Philip Ahn ever married and remained single their entire lives. Many have speculated that Ahn was gay but none have connected him to any potential male partners. Ahn’s biographer Hye Seung Chung offers a more nuanced reasoning in his book Hollywood Asian:

The polarization of Ahn’s sexuality in publicity and critical discourses attests to the complexities and contradictions surrounding Asian American masculinity and star image. Ahn often shuttled between two extreme stereotypes of Asian male sexuality (the beastly yellow rapist and the Oriental eunuch) throughout his screen career. His brief usurpation of normative heterosexual manhood in the late 1930s Paramount films assuaged white America’s racial anxieties and provided a short-lived possibility of the “Oriental Clark Gable” persona. Eventually, as this idealized romantic union was discontinued onscreen and unconsummated offscreen, American commentators and critics conveniently attributed his bachelorhood to homosexuality without considering the particularity of ethnic tradition and familial situations emphasized by the Korean press. Their Korean counterparts, on the other hand, automatically ruled out the queer potentiality of Ahn’s celibacy to keep their hetero-normative nationalistic imagination intact.

Moreover, AMW wasn’t really in need of a beard. She was preoccupied by her affair with Eric Maschwitz, the love of her life, who was doing a six-month stint in Hollywood as a writer at MGM. AMW was good at keeping her private life private. Plus, interracial marriage was still illegal, so Paramount certainly didn’t want to publicize their Chinese American star’s dalliance with a married British man. If anything, the rumors about Philip Ahn gave AMW cover for her ongoing heterosexual romance with Maschwitz.

Huang also asserts that around this time, “Anna May resumed her cozy relationship with Marlene Dietrich, who was shooting Angel on the same Paramount lot” (Daughter of the Dragon, p. 259). He cites Maria Riva again, mentioning that the two women would sometimes share cups of green tea in the afternoon. But we already know what Riva thinks about her mother and AMW having an affair—it never happened.

Huang finally admits the fact that he’s got nothing in the way of real evidence:

Unfortunately, except for these sketchy allusions that occasionally appear in the biographies of other stars, we know very little about how Anna May navigated the sub rosa lesbian world of Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s. Anna May’s rumored liaisons with Marlene Dietrich, Leni Riefenstahl, Dolores del Rio, and others were not the kind of sapphic love affairs openly discussed or graphically described as those in, say, de Acosta’s Here Lies the Heart (1960)—a controversial memoir that serves as an indispensable chronicle of “the sewing circle.” (Daughter of the Dragon, pp. 259)

But then, as if to distract us from this reality, he points to something else:

Instead, Anna May’s fluid sexuality manifested itself mostly in her myriad images, thus giving credence to contemporary feminist views that gender or sexual identity is socially performative rather than biologically determined. In her screen roles, vaudeville skits, and publicity photos, Anna May used costumes, coiffures, and gestures to curate an image of Oriental femininity, while also projecting a style of what would be called, in today’s lingo, “lesbian chic.” (Daughter of the Dragon, pp. 259)

So, AMW’s sartorial choices are evidence of her sexuality? I had to laugh at this. A straight man in his 50s, an ivory tower English professor, is the last person I would trust to identify fashion trends. Maybe he needs a primer on “today’s lingo” since “lesbian chic” dates back to the 1990s.

Huang also attempts to argue that AMW was queer by association, outed by the company she kept. He cites her partiality to Dragon’s Den, a restaurant in Chinatown run by AMW’s long time friend Eddy See:

In her final years, Chinatown remained Anna May’s most frequent destination, as it had been since the day she had learned to walk. Idle evenings often found the former Daughter of the Dragon relaxing, by Eddy and Sissee, both scions of the See family, the Den was a brick building sloping down a hill, with the sign painted in Chinese and English on the outside wall. Sporting dragon murals and funky music inside, the place, according to Lisa See, had become a haven for gays and lesbians. There Anna May, now a lonely celibate who had once liaised with countless men and occasionally women, could meet old friends like Keye Luke, Charlie Chan’s Number One Son; or James Howe and his Caucasian wife.

First off, Huang gets the timing completely wrong here. Dragon’s Den was only open for several years in the mid- to late-1930s. AMW did not spend her final years there. In fact, the building was destroyed sometime during the 1950s.

I agree that Dragon’s Den was an inclusive establishment, open to gays and lesbians, interracial couples, and creative Hollywood types, as Lisa See has documented in On Gold Mountain. But Huang seems to offer this open-mindedness as evidence that AMW herself was gay—which he reiterated in person at the MOCA event. I’ll say here what I said that night: Being an ally to queer folks, as Anna May certainly was, does not necessarily make oneself queer. Yes, she was friends with Ramon Novarro, Carl Van Vechten, Herbert Howe, Judith Anderson, and many other well-known queer figures. But arguing that she herself must have been gay in order to be friends with those people diminishes our understanding of AMW’s strength of character, her ability to accept people for who they were. In this, too, she was ahead of her time.

False Claim #5: Anna May Wong and Frank Dorn were lovers

Despite Huang’s obsession with AMW’s supposed bisexuality, he also slips in allegations of an affair between Anna May and American military attaché Frank Dorn. I’ve written about this theory and why it’s not true in LitHub, so I’ll give you the concentrated version here.

Frank Dorn, a West Point graduate and U.S. military aid, was stationed in Beijing when AMW arrived there in the summer of 1936. As two Americans intensely interested in art and the history of China (though Dorn was essentially an American spy, he was also a painter and writer), they became fast friends. This was an especially idyllic time in AMW’s life and she delighted in wandering the manicured gardens inside the walled homes of her neighbors and acquaintances in Beijing. Dorn, who was known to his friends as Pinkie, took a series of photos of Anna May in his private garden, including a portrait of them sitting together.

I’d seen the photo before on internet fan sites that hinted at a romantic relationship between the two. Huang takes these rumors a step further in his book:

With Pinkie’s help, Anna May found a place to rent on the same alley. . . . Since Pinkie and Anna May were both avid collectors of Chinese objets d’art, the curio shops, jewelers, and department stores lining Morrison Street, within walking distance from their alley, as well as the nearby Tung An Shih Chang, provided plenty for their picking. . . . Pinkie and Anna May probably also enjoyed forays to the Thieves’ Market. . . . When they tired of fooling around, Anna May and Pinkie could simply kick back and relax in their courtyards, enjoying the quiet hu-tong (alley) life. (Daughter of the Dragon, pp. 236-237)

For this information, Huang cites a biography of Frank Dorn by Alfred Emile Cornebise. I got a copy of the book but found no mention of Anna May Wong in it. Yet I could see the parts where Huang had clearly drawn his inspiration—Cornebise described Dorn doing all the same activities in Beijing, only without AMW. Confused and worried I was missing something, I reached out to Cornebise directly. He said he didn’t recall AMW’s name coming up in his research but told me to review Dorn’s 900-page autobiography at the Hoover Institution.

I hired a research assistant and fellow AMW expert, Rebecca Lee, to scan the appropriate pages for me at Hoover. What came back was surprising. Not only did Dorn not mention an affair between himself and AMW, he instead gossiped about her romances with other men!

Attractive and enveloped in the aura of Hollywood, men hovered around her wherever she went. . . . A young Britisher wanted to marry her, but she turned him down because she did not want to bring ‘half-breed’ children into the world. . . . But that busted romance in no way stopped her from a sizzling fling with Robert Faure, a French Embassy attaché. . . . Its searing heat singed the beach tents at Peitaho resort, at Tientsin and way points. But by the end of the summer, l’affaire Faure had petered out to cold ashes.

Either Huang decided to ignore Dorn’s autobiography, or he never bothered to look at it in the first place. Now, one could argue that even in light of Dorn’s admissions about AMW’s active love life, the two friends still could have had a sexual/romantic relationship. Well, sure, it’s technically possible. But given the circumstances, not likely.

The aforementioned claims and the evidence I have laid out debunking them reveals how Huang cut corners in his research process. (Btw, there are more issues with his work than I have cataloged here. I have only documented the most egregious ones.) He cherry-picked facts to support his theories, following his own confirmation bias, rather than developing theories supported by the facts. In many cases, he fabricated details to make his theories work and presented stories cut out of whole cloth. He frequently cited secondary sources without consulting primary sources that ultimately refute his theories. Is this the type of work expected from a tenured professor?

A clear theme emerges from the unsubstantiated allegations thrown around in Huang’s book. They are all related to Anna May Wong’s personal love life and sexuality. Biographies regularly tackle these aspects of a subject’s life, but one would expect an experienced biographer like Huang to take extra care in untangling such sensitive issues.

Instead, Huang treats her like a disposable China doll. He puts forth falsehoods about Anna May Wong that merely sensationalize and re-sexualize her, just as she was sexualized in life by the media and the Hollywood studios that relegated her to skimpy costumes in stereotypical roles. According to this logic, AMW is only of value if she can fulfill our prurient interests.

These rumors didn’t start with Huang. Previous male biographers like Hodges and Anthony B. Chan—who as far as I can tell are straight men—were some of the first to project this fantasy onto Anna May. But Huang took things several steps further, making leaps of conjecture based on flimsy or nonexistent evidence.

Huang’s reckless insinuations are damaging not only to AMW’s legacy, but also to biographical scholarship at large. For better or worse, once something is printed in a book, people believe it to be true even when it’s not. This is how misinformation gets repeated ad infinitum. Just look at Hollywood Pride, a TCM book published earlier this year that enshrines AMW on the cover as a gay Hollywood icon. (She can still be a gay icon without being gay, but this book seems to suggest the former.)

To be clear, I have no personal stakes in whether AMW was bisexual or queer. I simply care about telling the truth. While the possibility that AMW was queer has not been completely ruled out, evidence to support that conjecture has yet to emerge. I have frequently found myself in the awkward position of explaining to crestfallen fans that what they’ve heard about AMW’s bisexuality is nothing more than the fantasies of straight men.

What’s more, the false claims about her sexuality detract from the racist laws that restricted her love life. Even if she had wanted to marry, interracial marriage was illegal in California until 1947 and the rest of the country until 1967 (after she passed). Huang’s insistence on an explanation for her single status, like other male biographers before him, upholds our society’s tendency to characterize unmarried women (childless cat ladies) as spinsters, sad sacks, or in this case, lesbians. The most obvious explanation seems to slip past him: AMW received numerous marriage proposals over her lifetime; she simply preferred not to marry. With a love life like hers, why would she settle?

Books, however, are not held up to the same standards of newspaper or magazine journalism. They’re not fact checked unless the author takes on this cost themselves (publishers don’t usually pay for it). In my case, I paid a fact checker several thousand dollars to review my final manuscript; she caught a number of important mistakes and inconsistencies, which I corrected for publication. Even then, I have continued to catch small mistakes here and there—and one relatively big one.

Striving to tell the truth is no easy endeavor. But going out of your way to make up lies is another beast completely. So I’m left wondering, why would Yunte Huang make up these claims about AMW if there’s no evidence to support them?

The only thing that makes sense is this: He wanted to capitalize on a made-up story about a woman who is dead and can’t refute him. To make his research seem more sensational, more original than it is. To garner attention from the New York Times, the New Yorker, the National Book Critics Circle. To sell more books.

The urge to profit off of Anna May Wong with a bad faith interpretation of her story, to exploit her identity for personal gain, disgusts me. And I cannot abide by that type of behavior without calling it out. I care too much about her legacy to let one man’s sloppy, unethical claims stand unchallenged. Consider this my mic drop.

I admire all the work you've put into this piece, and into scrupulous AMW scholarship more generally. I'm intrigued that you spoke to Maria Riva in person. I read recently that she's still with us, nearly a centenarian. I envy you for being just that one single degree removed from not only your subject, but also so much other Hollywood history!

This such great scholarship! I'm going to share this with students in a queer history class I'm teaching at the moment, we've talked a lot about the challenges and ethics of recovering queer history. Also, from the point of view of a fashion historian, no way is that a bathing suit from 1919 and also lesbian fashions in the 1930s are simply not that different from the fashion straight women wore. Wearing masculine clothes was fashionable for women, in the context of a lesbian space it might have had a particular meaning, but it certainly isn't enough to suggest making a claim about someone's sexuality.