A Cigarette that Bears a Lipstick’s Traces

the woman who inspired one of the most famous love songs ever written

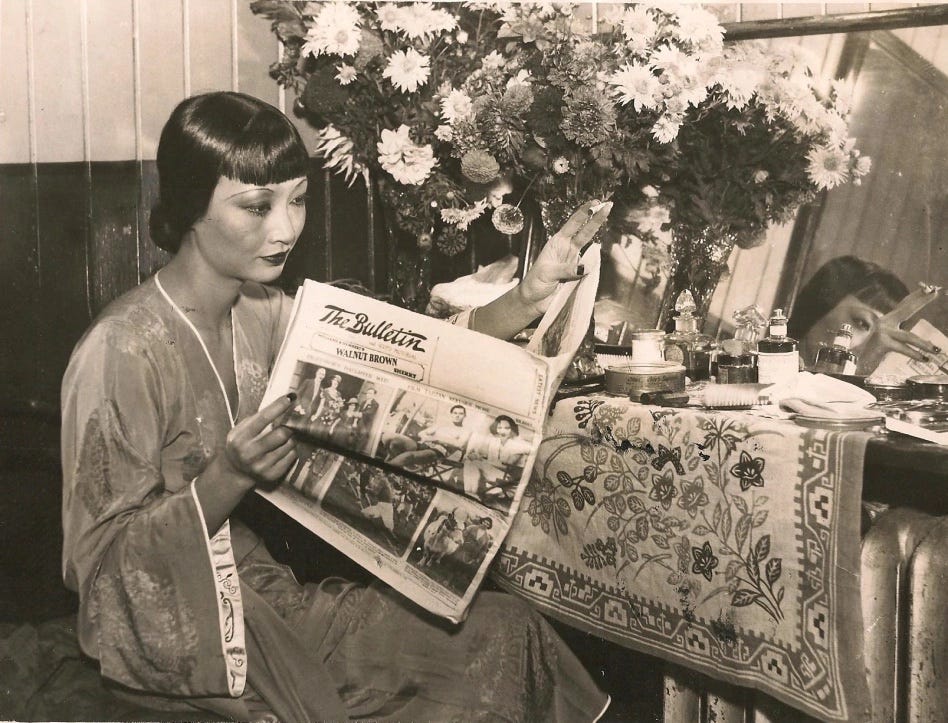

Anna May Wong had many lovers. She was a movie star, after all, and a legendary beauty at that. Her slim-cut figure and graceful gait seduced more than a few in her day, sometimes without her even trying. British composer Constant Lambert, who first set eyes on the actress as the Mongol slave in The Thief of Bagdad (1924), spent many a late night in his Bloomsbury flat toasting his Hollywood muse from across the Atlantic with cups of Chinese rice wine, and that was years before he’d ever met her in the flesh.

While anti-miscegenation laws in America, statutes that criminalized romantic relationships and marriage between whites and people of color, certainly complicated Anna May’s love life, it never stopped her from following her heart. In London, where there were no such legal restrictions, Anna May was quite the regular on the high society social circuit. When she returned stateside, she slyly boasted to a reporter, “Well, for many months I did not buy myself a single meal.”

The men Anna May Wong fell in love with were often brilliant artists in their own right—composers, writers, filmmakers—visionaries who had something to say to the world.*

One of them, perhaps the most memorable of all, was Eric Maschwitz, a multi-talented literary man who sometimes went by the jazzy pen name Holt Marvell. He was an editor and later variety director at the then fledgling British Broadcasting Company (BBC). In his spare time, he wrote novels and the West End hit musical Balalaika (1936). In Hollywood, where he was lured by the slick execs at MGM who promised him a massive payday, he co-wrote the screenplay for Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939), for which he received an Oscar nomination. But his most famous work, the thing that outlived him and was reborn a hundred times over, was the standard “These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You).”

Whether you can recall the tune, you’ve surely heard it before. Leslie Hutchinson’s rendition was the first to make the song famous, but every major artist you can think of in the standard music genre has covered it: Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra, Thelonious Monk, Etta James, Chet Baker, Nat King Cole, Tony Bennett, Aaron Neville, Rod Stewart, Michael Bublé, Seth MacFarlane, Emmy Rossum, and even Bob Dylan (if you can imagine that).

The lingering question in everyone’s mind has always been: Who was the song written about? Eric never said one way or the other. In truth, his account of how the song came together, which he included in his 1957 memoir No Chip on My Shoulder, was much more matter-of-fact than the rumor mill would have you believe.

As the new director of the BBC’s variety programming, Eric began commissioning radio musicals and inviting an assortment of musicians, singers, actors, and other entertainment acts onto their weekly revue. He and Jack Strachey, his music writing partner, started penning songs for the show themselves. So when one of their actresses needed an original tune to sing on the air, he and Jack decided to take a crack at it.

One Sunday morning in my flat in Adam Street, only half-recovered from six eighteen-hour days in the studios, I sat in pyjamas, unshaven, considering the problem of a song for pretty Miss Carr. Cole Porter in the musical play Anything Goes had recently broken new ground with a cynical rhythmic ditty entitled “You’re the Top”; his formula (which has since become known as the “catalogue song”) might, it seemed to me, be applied in a more romantic vein; every one of us must have small, fleeting memories of Young Love. By some accident I hit upon the title “These Foolish Things” and, then and there, between sips of coffee and vodka, I drafted out the verse and three choruses of a song.

Many, including Hermione Gingold, Eric’s wife at the time he wrote the lyrics, assumed the song was an homage to Anna May. (Of course, that was after Hermione realized the song wasn’t about her, as Eric originally told her it was.) But others, like British journalist Peter Frost and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, assert that Eric Maschwitz must have been thinking of Jean Ross—an actress, journalist, activist, and the woman who inspired novelist Christopher Isherwood’s character Sally Bowles, later immortalized by Liza Minnelli in Cabaret (1972). Jean, apparently, had an affair with Eric in the early 1930s, and for whatever reason, some believe that Eric’s reference to “fleeting memories of Young Love” must refer to Jean.

But this rather thin stack of evidence has never sat right with me.

Despite Eric Maschwitz’s unassuming appearance—tall, lanky, pale—he was an inveterate playboy. He shacked up with his first wife, Hermione, while she was still married . . . to his boss. Hermione promptly divorced her husband and married Eric so that they could uphold the veneer of respectability. The honeymoon didn’t last long. Hermione soon discovered Eric was sleeping with her cousin and one of her friends. They remained married for nearly 20 years but in name only, while both pursued various paramours.

I don’t doubt that Jean and Eric might have had their own dalliance, but knowing what a cad Eric was, always falling in love with a new bird, who’s to say the song couldn’t have been about any number of ladies he had flings with? The song could just as likely be a composite of several women or all of them.

Still, it’s worth mentioning that Anna May figures prominently in Eric’s memoir, perhaps more than any other woman. It was her lasting influence on him that roused him to profess, “The Chinese are a remarkable people; everyone should know and love at least one educated Chinese person in their lives.” These words were written almost 20 years after his affair with AMW ended, while he was “happily” married to his second wife, Phyllis Gordon.

I think you see where I’m headed? I’d like to put this guessing game to rest. Because if you read the lyrics closely, there is only one woman who evokes the trifling, foolish flights of fancy that we call love. Hear me out.

Eric Maschwitz’s catalogue song begins like this:

A cigarette that bears a lipstick's traces

An airline ticket to romantic places

And still my heart has wings

These foolish things remind me of you

The first line is the one Jean Ross insisted belonged to her. Yet Anna May wore plenty of lipstick, and she smoked enough cigarettes, like every chic woman of her era, to occasionally leave behind “a lipstick’s traces.”

As for airline tickets, Eric and Anna May were involved in an international romance that spanned the 1930s, with rendezvous in New York, London, Hollywood, and very likely the South of France. When Eric flew from New York to Los Angeles in 1937 to commence his screenwriting contract with MGM, Anna May was at the airport to greet him and dash him away from the pressmen lying in wait for the latest Hollywood newbie. During his six-month stint in L.A., Anna May showed Eric the sights: “the beach at Santa Monica, the unreally beautiful racecourse of Santa Anita, the desert oasis of Palm Springs.” All romantic places, no?

A tinkling piano in the next apartment

Those stumbling words that told you what my heart meant

A fair ground's painted swings

These foolish things remind me of you

Eric first met Anna May in New York in the spring of 1932 through mutual friend Cedric Belfrage, an entertainment reporter for London’s Sunday Express. As he recalled in his memoir, Eric was so nervous in Anna May’s presence that he barely spoke at all that first meeting. Yet somehow his “stumbling words” managed to convey his instant infatuation. Could this be the moment their affair began?

First daffodils and long excited cables

And candle lights on little corner tables

And still my heart has wings

These foolish things remind me of you

So it was spring when their love first blossomed. But soon, Eric and Anna May would have been separated by oceans and continents. How else could they have communicated except through letters and “long excited cables”?

The park at evening when the bell has sounded

The "Ile de France" with all the gulls around it

The beauty that is Spring's

These foolish things remind me of you

We don’t know whether the pair ever went for twilight strolls through Central Park before they parted, but it sure is pretty to think so. One thing is certain. When Eric sailed back to England, he watched the New York City harbor recede into the distance from the deck of the Ile de France, the luxury liner known to shuttle the young, fashionable set back and forth between Europe and America.

Gardenia perfume ling'ring on a pillow

Wild strawberries only seven francs a kilo

And still my heart has wings

These foolish things remind me of you

Anna May often wore fragrances by Guerlain and she loved flowers, so it’s not a stretch to think she may have spritzed herself on occasion with a gardenia scent. And “wild strawberries only seven francs a kilo” sounds like something you might buy at the local market while on summer holiday in Juan-les-Pins, where Eric once vacationed with an unnamed lover. I speculate in my book that it was Anna May.

The smile of Garbo and the scent of roses

The waiters whistling as the last bar closes

The song that Crosby sings

These foolish things remind me of you

Greta Garbo, the Swedish sphinx, was one of Hollywood’s most talked about stars and also considered its most elusive. Her foreign beauty and enigmatic personality (she never gave interviews) earned her the reputation of an exotic hothouse flower, the frosty temperatures of her native Sweden notwithstanding. Anna May Wong, who many termed “exotic” for different reasons, was often compared to the great Garbo for her subtle yet evocative facial expressions. But the imagined mystery of an Asian actress like Anna May also imparted a similar effect as Garbo, it left the viewer wanting more.

If I haven’t convinced you yet, here’s the last link in the chain. By the end of his MGM contract, Eric had realized he despised screenwriting, which in his experience entailed sitting around most of the time and swinging by the studio on Fridays to pick up his check. What little he did write was reworked and reworked, sometimes by other studio writers, until he no longer recognized the material as coming from his own hand. This listless Hollywood life was not for him. So he packed up his bungalow and made plans to return to England.

This time around, he waved off the airline ticket and decided to take the train back to New York. On the platform, he said his final goodbyes to a group of friends with tears in his eyes, most cherished among them his dearest Anna May. As he recalled this moment of finality in his memoir, Eric added:

In the Age of the Aeroplane it is my advice to all travellers not to lose sight of the Railway Train. . . . I am still under the spell of “the puffers,” the clanking, shunting magic which I tried to capture in a line of a song: The sigh of midnight trains in empty stations . . .

That song, whether Eric Maschwitz intended it or not, forever enshrines his romance with Anna May Wong, an unrequited love story if there ever was one. For what is great art meant to do if not to capture the secret histories of the heart and make them legible for all eternity?

Anna May and Eric didn’t leave a paper trail of their years-long affair. There are no steamy letters, no lovesick cablegrams, no treasured snapshots, no passionate notes scribbled on the back of cocktail napkins for us to examine. But maybe, just maybe, one song is enough.

*Some have speculated that Anna May was queer and had relationships with women, which is entirely possible. Hollywood was the kind of place where one could explore their sexuality, at least behind closed doors. Love affairs with the same sex were both open secrets among members of the film colony and kept strictly under lock and key from the prying eyes of the public. My research, however, has failed to yield evidence that Anna May pursued romantic relationships with women.

March Madness

March 2023 was one of my busiest months yet! ICYMI, I got my first byline in the New York Times writing about Anna May Wong and other early Asians/Asian Americans in Hollywood on the eve of the 95th Academy Awards. Suddenly, I found myself, a little known “Hollywood historian,” thrust into the 24-hour news cycle, talking to Yasmin Vossoughian on live television. I still maintain I did it all for Room Rater. Oh yeah, and the sweet, sweet icing on the cake was getting to watch EEAAO sweep the Oscars.

A warm welcome to those of you who flocked to this newsletter as a result of my NYT guest essay. I’d love to hear what you’re interested in learning about AMW in future installments, so leave your thoughts in the comments.

But that’s not all March had in store for me. I also made a last minute return trip to Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, finalized photo selections for my chapter openers, finished up revisions on the book, and submitted the final final manuscript to my editor. Woohoo! I have been enjoying this feeling of accomplishment, but most of all the sheer relief and the luxury of catching a few extra winks.

Another unexpected bonus was receiving early cover art concepts from my publisher. My jaw dropped when I saw what their brilliant designer came up with. While the concepts were all impressive, there was one clear winner, and I can’t wait to reveal the cover to you all in the coming months.

One more thing I want to mention: This newsletter has always been free and is going to stay free for the foreseeable future. But it has come to my attention that there are a number of readers out there who would like to send a few dollars of appreciation my way every now and then. For those of you who feel so moved, you can find me on PayPal. Please know that however you are able to contribute, whether it’s through likes, comments, or donations, anything and everything is appreciated. As long as I’ve got readers, I’ll be here writing.

I am now convinced the song was written by Maschwitz as an Ode to Anna May Wong and to no-one else.

The time lines don't work to support anyone else. The words of Ms. Gee Salisbury, re-read, convince me.

The assertions by an Oxford "Dictionary" of Biographies that the lyric poem are insufficiently based in fact. The perseverate efforts on-line to assert that the lyrics were written for Jean Ross are not fact-based.

This is based on careful re-reading of Maschwitz's book, "No Chip on My Shoulder" and after reading this blog post again.

This is based also on listening to the first recorded version of the song, by Leslie Hutchinson. Review of Parlophone records indicate the song was recorded in February, 1936. Review of numerous sources indicates that the Parlophone catalogue number was F 373, and the "F" reflects recorded in February. 1936.

Based on review of the original, complete, lyrics, "Hutch", as recounted by more than one source, and balked at singing the words "silk stockings thrown aside" in his, the first recorded version, in February 1936. He was fearful of censorship.

In fact, he substituted the words "two lovers on the street" for "silk stockings...." then followed by "dance invitations" in that February 1936 recording. Consistent with his censorship concerns.

Of great import are other clues. Maschwitz, in his book, indicates that he had originally written the song for a BBC radio revue, apparently only broadcast once, about early 1934. Not in a subsequent _stage_ revue, "Spread It Around". in 1936, as widely reported.

This is supported by Maschwitz's recollection that the song, with Jack Strachey musical score, was found by "Hutch", gathering literal dust, on top of the piano in Maschwitz's BBC offices, approximately two years after written. Consistent with an early 1934 writing.

The song did, in fact, gain almost immediate traction in the States after Hutchinson's February 1936 recording.

On June 15, 1936 it was recorded by Benny Goodman's Orchestra, vocal by Helen Ward, Victor Record 25351-"B", and soon rose high on the weekly US radio show, "Your Hit Parade". The song was, in view of communications at the time, an almost immediate hit.

Ms. Gee Salisbury's recounting of the first meeting of Wong and Maschwitz indicates it to be in spring 1931. Wong returned to LA, with a Paramount contract, not later than the beginning of June, 1931.

The song mentions daffodils blooming; they are an early spring flowers in New York. Mid-April, certainly. Again, consistent with whatever time they may have had together in 1931.

Wong and Maschwitz met again in person not later than fall, 1933. We know that because Wong was doing her cabaret tour of Europe at that time, and specifically the British Isles in October, 1933.

More specifically, she took time off to see a revue in Leeds. Maschwitz participated in the performance. She was an inveterate collector of show programs [see, the massive collection at the Billy Rose Library at Lincoln Center, New York].

She obtained autographs of many of the performers, which are written carefully, or scribbled in the margins.

After consulting with Michelle Yim of Red Dragonfly Productions in Great Britain, who has performed numerous recreations of Wong's cabaret performances, the location of Maschwitz's signature in the very center is indicative that he was first to sign the program.

Furthermore, he used his pseudonym, "Holt Marvell" for his autograph; it was an inside joke, showing familiarity. When the song was recorded, she would immediately know the lyricist. When almost all others would not.

Ms. Gee Salisbury also recounts how, in Maschwitz's book, he pairs his last farewell to Wong in California at a train station in conjunction with and proximity to the lyrics of the song.

Further careful review of his words about that departure may be warranted.

A second or third review of Ms. Gee Salisbury's words, my own research, and the research and insights of Michelle Yim leads me to agree there is no reasonable possibility that Maschwitz wrote the lyrics as an Ode to anyone but Wong.

It is further buttressed by my review of Wong's personal collection of musical scores at the Houghton Library at Harvard and the Wong Theater Collection at the Billy Rose.

I was assisted in review of the documentary evidence by Michelle Yim, who may or may not agree with all of my conclusions.

The conclusions of the Oxford "Dictionary" of Biography about Maschwitz's lyrics is, at best, fundamental error.

The perseverate rewriting of the story of the song in a major on-line encyclopedia indicates, to me, a rigid adherence to a narrative that careful review and consideration of newly presented facts shows to be untrue.

The song is not to "nobody in particular", it is not "for" Jean Ross [aka "Sally Bowles" of "Cabaret"]. Did Maschwitz tell others it was for them, not Anna May Wong? Certainly. Truth will out. He knew when he wrote his book that Wong would know it was a lyrical poem to her.

The predictions of a journalist in a San Francisco in 1921 would, with this song, become a fundament truth of her life.

She would learn the "mysteries of traveling by night". And in the lyrics, immortalized.

Interesting article and enjoyed it. Thank you.