Three Women Walk into a Berlin Ball

the shutter click that immortalized Anna, Marlene & Leni

Berlin in the late 1920s was a surreal place. For the Weimar Republic’s greatest artists and bohemian visionaries, the city offered safe harbor and a space in which to experiment freely. At the same time, Berlin symbolized all the stuff that hedonistic dreams are made of, or depending on how you look at it, the death spiral of a decadent, self-destructive society.

After years of penury, of scraping by to do one’s part to support the German struggle in World War I, then grappling with the shameful fallout of Germany’s defeat in 1918 and the financial burden of owing millions of dollars in war reparations, Berliners simply longed to forget, to keep moving, to live for today only (and for the long night to follow). By 1927, Germany’s economy had picked up and Berlin, like many cosmopolitan cities around the world, had embraced the freewheeling ethos of the American Jazz Age with feverish abandon.

Every night was a cabaret, an avant-garde play, a supper club soirée. All the men were pretty and the women were strong, and if it mattered to you whether the sexy young thing who just joined your table was a man or a woman or something else on a gender fluid spectrum that didn’t yet exist, well, then you’d come to the wrong place. “The only rule was that if a man beckoned a pretty girl, she must prove when she came to his table that she really had breasts,” Hollywood biographer Charles Higham wrote of this period in Berlin. “Often, the unwary male could find himself caressing the leg of a well-known athlete dressed in convincing drag.”

Anna May Wong arrived in Berlin amidst this backdrop in April 1928. Frustrated with Hollywood’s typecasting, she had sailed for Europe with her older sister Lulu in tow to make a film for UFA, Germany’s premiere motion-picture company. Anna May’s presence in Berlin caused an immediate stir. Society hostesses and public intellectuals alike, Walter Benjamin among them, were dazzled by her beauty and wry repartee. Aspiring actresses jockeyed to brush arms with AMW at parties on the odd chance that some of her superlative Americanness might rub off on them.

The most famous of these instances has been enshrined forever in a series of pictures made by a young, relatively unknown photographer. His name was Alfred Eisenstaedt. Within a few years, he would be on his way to the U.S. to become one of LIFE magazine’s original staff photographers. Even if you haven’t seen the picture I’m referring to, you’ve undoubtedly seen many of Eisenstaedt’s iconic images (they may be unwittingly seared into your brain thanks to pop culture). For example, he took that famous picture that came to symbolize the end of World War II for Americans: a sailor exuberantly kissing a woman in Times Square during victory celebrations.

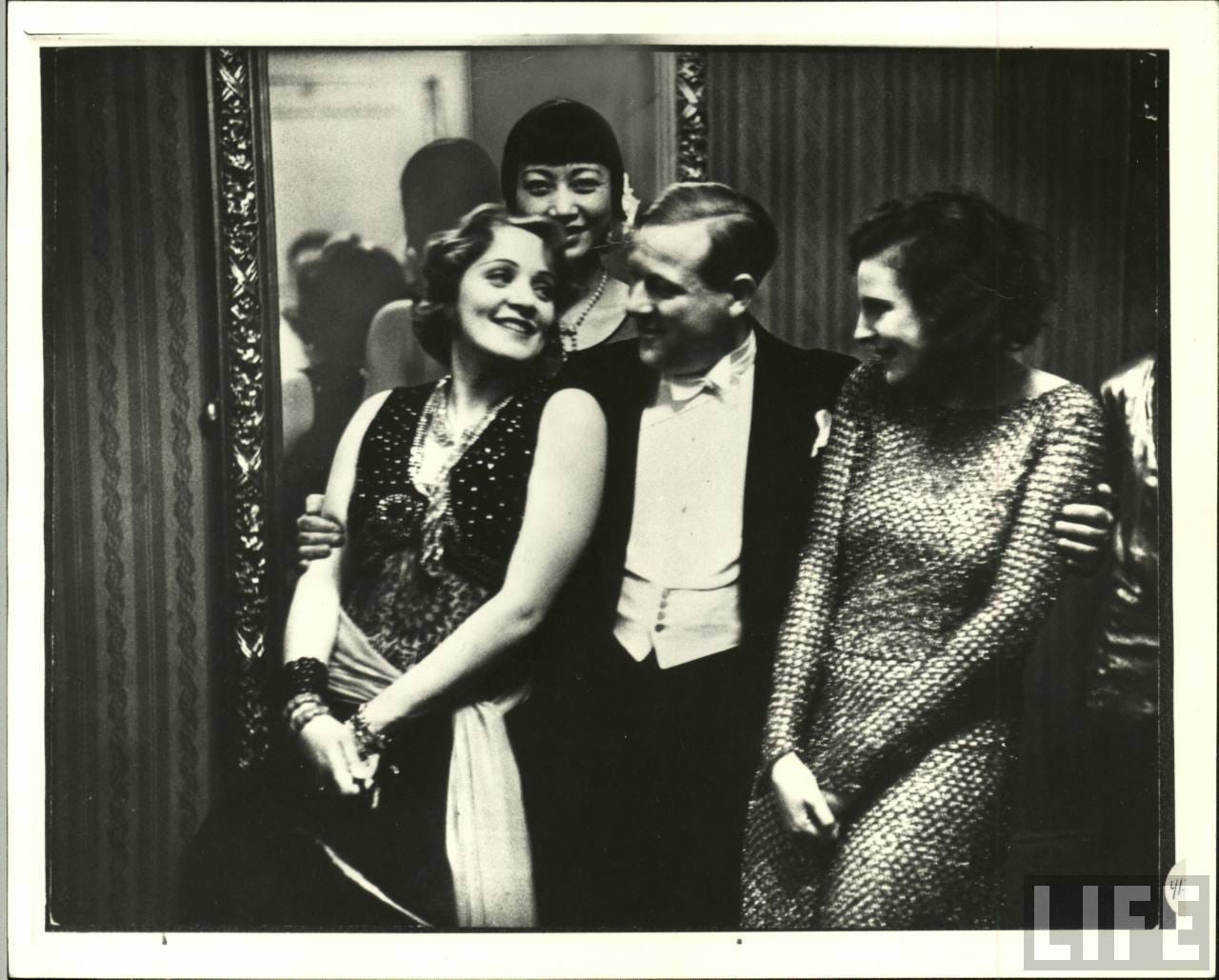

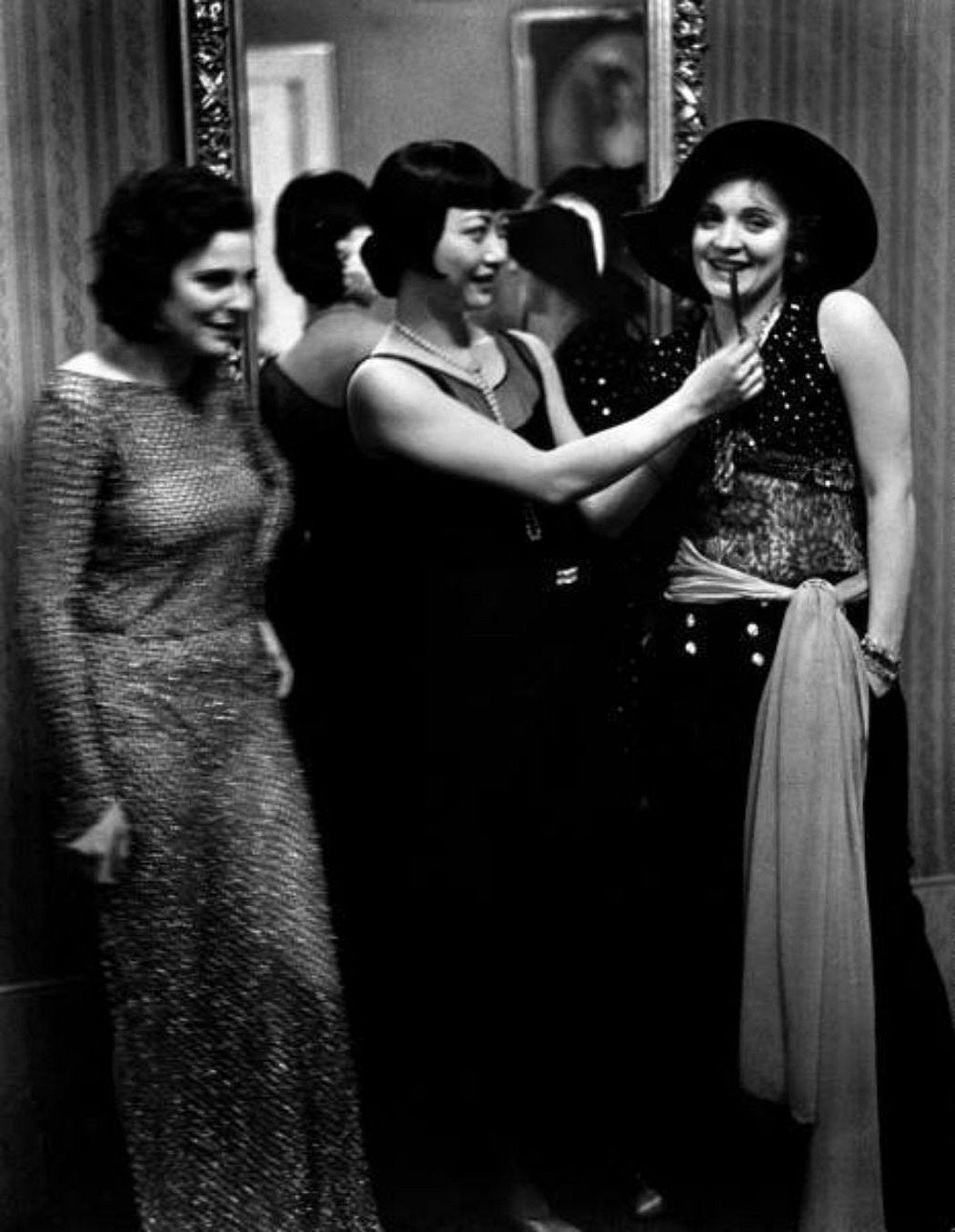

But back to the photo in question. Three beautiful, ambitious women, their arms clasping one another, stand in front of a gilded mirror, posing for our photographer. At the time the picture was made, only one of these women was famous. The other two were still nobodies merely playing at being somebodies, posturing for the fame they hoped was lurking just around the corner. Maybe this photo is a lesson in wish fulfillment.

Anna May Wong, the American movie star, is at the center of the clique, the atomic nucleus of this threesome. She is flanked by Marlene Dietrich on the left, then an actress of middling success in the Berlin theater scene who’d recently gained notoriety among Berliners for singing “My Best Girlfriend” with Margo Lion, a nascent Lesbian anthem. And on the right Leni Riefenstahl, an aspiring actress with even fewer credits to her name.

A simple, and rather popular, reading of this photograph suggests that these women are partaking in the debaucherous Berlin nightlife—together. AMW biographer Graham Russell Gao Hodges writes in his 2004 book: “Gay women were everywhere in Berlin, and arriving at a party with someone of the same sex simply proved one was modern. The clear intimacy found in Eisenstaedt’s photos strongly suggest that Anna May had a fling with Dietrich and possibly Riefenstahl . . .”

It’s no secret that Marlene Dietrich was a libertine who followed her pleasure wherever it might lead. She seduced men and women alike. As Donald Spoto, one of her many biographers put it, “Dietrich openly discussed her casual amours, which included men from film studios with whom she spent an occasional night, actors from the theater who she thought required a little attention, and those like Anna May Wong and Tilly Losch, who were clever, amusing and exotic companions. She did not proffer sex as barter, to win a role or a favor; it was simply an acceptable form of flattery and a way of being appreciated.”

Clearly, there is some chemistry between Marlene and Anna May, which we can see as the latter playfully positions the pipe in her saucy new acquaintance’s mouth. They’re having a fine time. But as titillating as it might be to fantasize about Anna, Marlene, and Leni enmeshed in a ménage à trois of sorts (in fact, novelist Amanda Lee Koe dedicated an entire book to dramatizing the personalities caught in the image), that version of events feels a little too pat to me. It’s a bit obvious, no?

I’ve spent many hours pouring over this photograph and others from the same evening. I’ve lost whole afternoons, when I should have been reading or writing, to dead-end Google searches. I’ve clipped articles I can’t read from German newspaper archives and purchased several out-of-print Eisenstaedt photo books on eBay. I’ve trawled Getty Images in an attempt to compare the wallpaper and curtains in the background with those of the Hotel Adlon and other possible venues where this fateful meeting might have taken place.

The only thing I know for sure is that photos can lie, if we let them. And sometimes books do too. That’s not to say I don’t have my own theory about what’s really going on in this photograph, because I do.

The problem is I ask a lot of questions. The two most basic ones—when and where was this photo taken?—have nearly driven me to madness. No one seems to agree. Various sources date the photo to 1928 or 1930 and suggest several different locations in Berlin: the annual Berliner Presseball, the Reimann Art School Ball, the Marmosaal at the Berlin Zoological Garden, or a private soiree given at Karl Vollmoeller’s home. These unverified statements have been repeated and proliferated across the Internet without anyone really knowing if they’re true or not. There’s no there there.

So I went back to the original source, or as close as I could get. In the caption to the photo in his book Eisenstaedt on Eisenstaedt (1985), the photographer writes, “I first photographed [Marlene Dietrich] at the famous Reimann Ball, which everybody went to. She had just finished the movie The Blue Angel.” To cross-check, I also looked at what he said ten years before in another book called People (1973): “Marlene Dietrich in Berlin, 1928, the year her acting in The Blue Angel earned her a Hollywood contract. . . . At an artist’s ball with Anna May Wong.”

I would love to take old Eisie at his word, but his captions are riddled with factual inconsistencies. From what I’ve been able to gather about the Reimann and Press balls, both were annual events that took place around the beginning of the new calendar year in January and February. AMW arrived in Berlin in April 1928. She couldn’t have attended any of Berlin’s balls that year. Another outtake shows a man thrown into the mix. Internet sleuths have guessed at who he might be without much luck, but I recognized him instantly as Richard Eichberg, the man who directed Anna May Wong in the UFA films Song, Pavement Butterfly, and The Flame of Love (she would have been shooting the latter film around this time).

As for The Blue Angel, that was the film that made Marlene Dietrich into the international star that we remember her as today. But she didn’t begin work on the film until November 1929, and she’d only met her muse-lover-director Josef von Sternberg a month or two before that. Eisenstaedt was just starting out in his career as a photojournalist then (he’d recently quit the button-selling business) and it’s quite likely his memory of this early photo is hazy. He himself once said, “From a photographer’s point of view, the most important thing is the picture itself, not the subject matter or the year in which, by chance, it was made.”

Among the series is a photo of Josef von Sternberg and Marlene together. Which says to me there is no way this evening could have taken place before October 1929. Production on The Blue Angel wrapped on January 22, 1930, and Sternberg left for Hollywood shortly thereafter. If the photo’s subjects were cavorting at one of the new year’s balls, and Dietrich and Sternberg had indeed just completed their first film together, January 1930 is the most plausible date.

Once you know the rough timeline surrounding this event, the chips begin to fall into place. The idea that AMW, Marlene, and Leni were all sleeping with one another starts to sound a little preposterous.

From the moment he first saw her on stage in a Berlin theater, Josef von Sternberg was obsessed with Marlene. Their work together on The Blue Angel marked not only the start of their collaborative relationship across six films, but also the beginning of an intense sexual affair (both were married, but Sternberg didn’t remain so for long). While it’s possible AMW and Marlene may have had some kind of intimate episode, Sternberg was the lover that dominated Marlene’s life during this period. John Baxter, Sternberg’s biographer, writes, “Dietrich’s capacity to annihilate him was among her greatest attractions. On the set, he was her master, but in the bedroom, she held him in the palm of her hand.”

Marlene knew what she was doing in front of the camera. Though she tried to play at being coy, she had long ago set her sights on building herself a cult of celebrity. As scholar Patrice Petro notes, in those days she often asked photographers to “take some picture of me that will make me a star.”

And what of Leni Riefenstahl? Well, in Marlene’s eyes, she was the worst kind of social climber—an unsuccessful one. Her attempts to launch herself as a dancer and alternately as an actress were mixed at best, despite the generous funding of her wealthy patron Harry Sokal. Then in 1925 Leni landed her first German film role as the mountaineer in director Arnold Fanck’s The Holy Mountain.

Leni and Marlene ran in the same Berlin theatrical circles. At one point they even lived in the same building. They knew each other in that side-glance, IG stalker kind of way because they were competing for the same roles. In her memoir, Leni would later claim she was one of the front-runners in consideration for the Lola Lola role that Marlene played in The Blue Angel; she bragged that she had dined privately with Josef von Sternberg; etc. Their rivalry ran deep, and though Marlene undeniably surpassed Leni as an actress, she continued to hate the woman who would go on to become Hitler’s director until her dying day.

Eisenstaedt’s photo of Anna, Marlene, and Leni is startling for any number of reasons. Glamorous women from past eras are bewitching in their own way. Who doesn’t love to see AMW in her flapper getup, pearls knotted around her neck, and Marlene Dietrich dressed up as a sexy pirate with a lit pipe dangling between her lips? Who knew there was a softer side to Leni Riefenstahl, the woman behind the greatest propaganda film of all time?

More than anything, looking at this photograph is like reading a novel where everyone knows how the story will end except for the characters themselves. The real drama is watching the inevitable come to fruition.

In a few months time, The Blue Angel would premiere in Berlin and Marlene Dietrich would board a ship headed for America the very same night, to launch her Hollywood career at Paramount Pictures and continue her mind-body-soul meld with Josef von Sternberg. Adolf Hitler would become chancellor of Germany in 1933 and bring a violent end to Berlin’s permissive culture of artistic and sexual experimentation. Leni Riefenstahl would sidle up to Hitler and charm the man who had been spurned by her rival. (The Nazis invited Marlene to return to Germany to take her place as the reigning German film star, but she famously declined. The Third Reich banned The Blue Angel, though it was rumored Hitler had a private copy that he rapturously screened in his private cinema.) Leni would embrace her adventuress persona and throw her hat into the ring as a filmmaker and mythologizer of Aryan origin stories (mountain imagery abounded), directing The Triumph of the Will in 1934.

Then we come to the Chinese American woman in the middle of it all, the person whose name many no longer recall, if they ever knew it to begin with. They know nothing of the incredible life that led her to this precise moment in history, but her presence in the photo signals that she too must be extraordinary in some way.

The first time I saw this photo, I must have been 19 or 20. I remember a pang of nostalgia and longing wash over me. What a life! To have lived during such crazy times! To have partied with Marlene Dietrich and Leni Riefenstahl! The picture validated for me AMW’s stature as an international movie star and personality. But when I look at it now, I see something very different. I think of all the things that AMW could not have known in that moment. How two ruthlessly ambitious women would swiftly surpass her in notoriety and supposed historical value.

AMW and Marlene would meet again in a year’s time in Hollywood. Except the tables had turned. Marlene was now the star of Josef von Sternberg’s Shanghai Express and Anna May was the woman in her shadow (though she managed to shine from underneath it anyhow). The two women were still friendly. “Between takes, they talked, not rehearsing their scenes, just soft conversation, smoked, sipped cool coffee through their straws,” Marlene’s daughter, who accompanied her on all of her films in those days, recalls. “She liked Miss Wong much better than her leading man.”

Strange then, that Marlene fails to mention AMW in her 1989 memoir. In fact, she doesn’t say a single word about Shanghai Express, one of her most successful and lauded films. Perhaps she thought better of referring to the one movie in which she played alongside another actress who dared to hold a candle to her, who almost stole the film, who remembered the unknown German actress she had once been.

Besides, it was 1989. Anna May Wong was dead and buried and her name had long since disappeared from newspaper headlines and society gossip columns. AMW had been written out of the history books. What did Marlene stand to gain by dredging up the past? The picture said exactly what she wanted it to.

Excellent work. I come up with the same conclusion. Blue Angel came out April 1, 1930. Marlene is wearing her "Pirate Jenny" outfit from "Blue Angel". Riefenstahl indicates same about Marlene just done filming. Riefenstahl is like a coconspirator turning state's evidence-all her statements must be backed up with physical evidence to be believed. It's early 1930.

“More than anything, looking at this photograph is like reading a novel where everyone knows how the story will end except for the characters themselves.” YES!