The Warmth of Other Suns

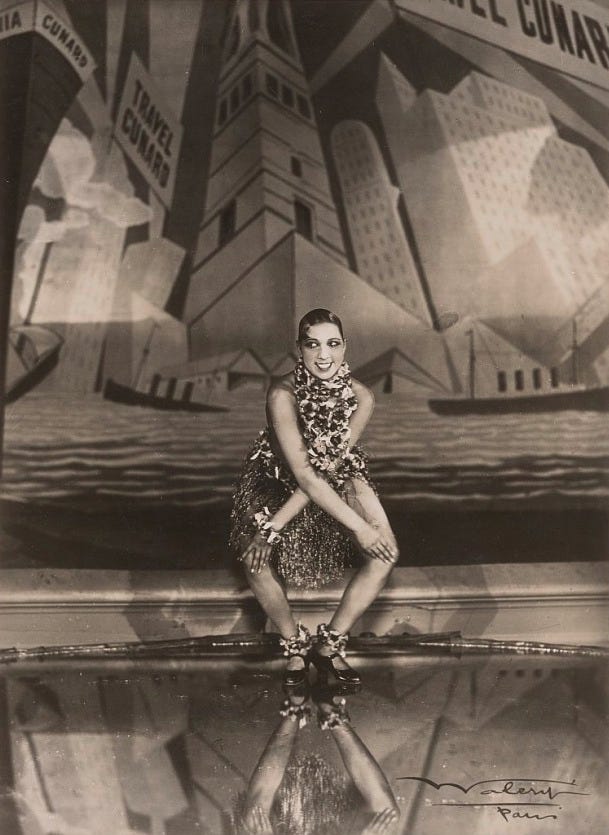

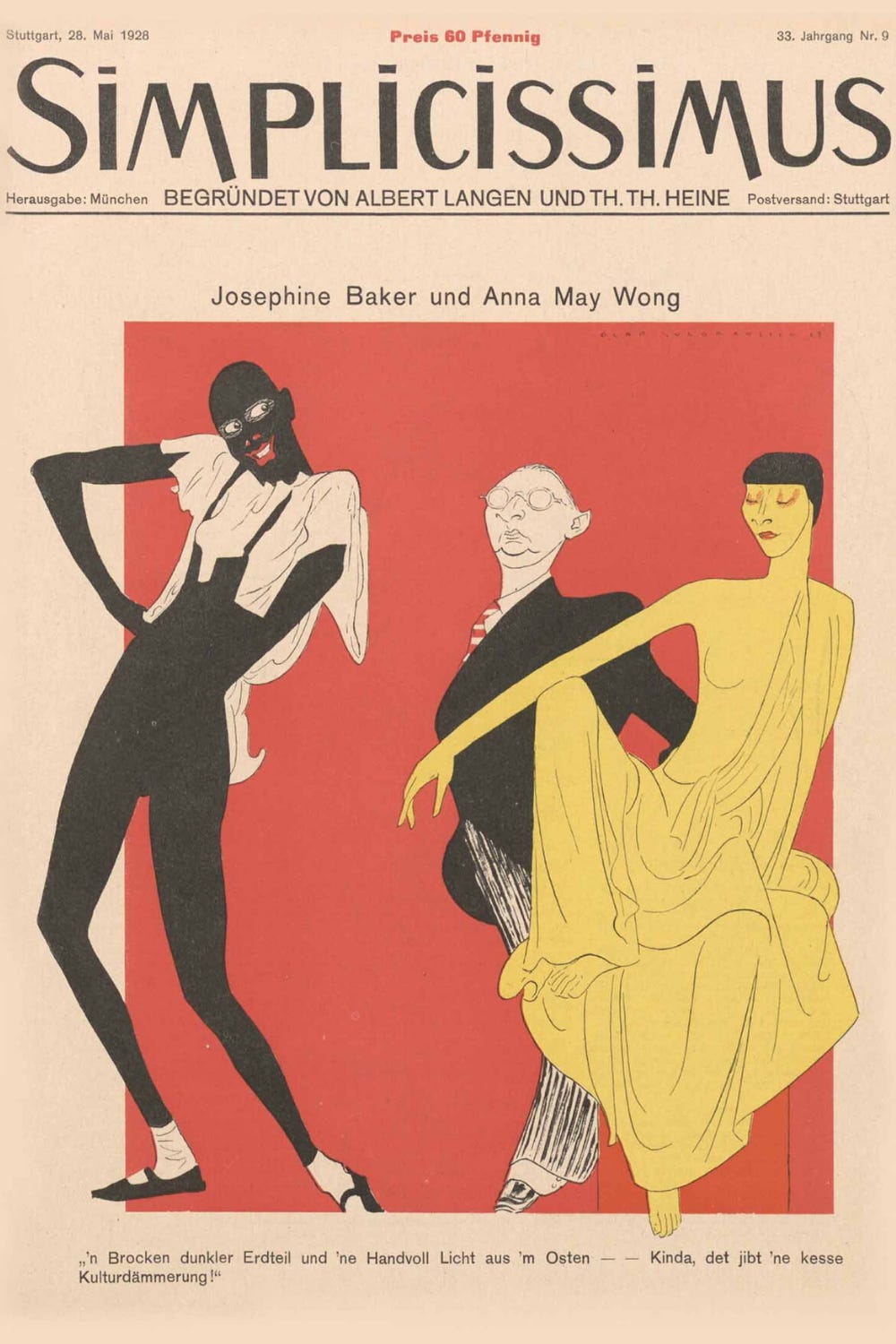

how Paul Robeson & Josephine Baker’s success in Europe paved the way for Anna May Wong

The story of Anna May Wong’s sojourn in Europe has become the stuff of legend. Seeing that there was nothing for her in Hollywood—except the same old exoticized roles where she never got the guy and died in the end (or sometimes died at the very beginning)—she gathered up every ounce of her youthful gumption and set sail for Germany in the spring of 1928. At UFA in Berlin, not only was Anna May cast in the leading role, but the screenplay was crafted specifically for her and the film was retitled in honor of her Chinese name, to boot! (If you ask me, Song is still one of the best films she ever made.)

By the time she returned to the U.S. three years later, she had been hailed as an international sensation. Studio heads suddenly realized they’d better give the Chinese American actress a second look. Los Angeles Times reporter Harry Carr put it this way: Anna May had to leave Hollywood “to glow and dazzle… Now that she has become world famous, Hollywood tries to assure us that they knew her all the time. But this is not true.”

Anna May, of course, was not the first entertainer of color to prove her mettle on the other side of the Atlantic. It’s impossible to talk about this period of her life without recognizing the exodus of Black American performers who first made the leap to Europe. The most famous among them were Paul Robeson and Josephine Baker, whose groundbreaking careers paved the way for someone like Anna May to follow in their footsteps.

The woman who became known as the Black Venus was born Freda Josephine McDonald in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1906. Her mother was a washerwoman who sometimes performed in a local vaudeville act with drummer Eddie Carson. Little is known about her father, who many speculate was white or mixed race. Josephine stuck out as a young girl, even among her half-siblings, on account of her lighter complexion. The kids at school made fun of her and called her father a “buckra,” a derogatory term for a white person that comes from a West African word meaning “European” or “master.”

Racial tensions in the South made an indelible mark on her as a young girl. Her posthumous memoir, Josephine, opens with the most traumatic scene of her childhood: A white lynch mob descends on their village, intent on rooting out the man a white woman has accused of raping her. Though Josephine’s family eludes bodily harm, her 11-year-old eyes still witness the mob scratching a man’s eyes out and ripping out the unborn child from a pregnant woman’s belly. It’s easy to understand why such a horrific scene never slipped from her memory.

Growing up in extreme poverty, Josephine learned early how to survive. Occasionally that meant combing through other people’s garbage to look for scraps to eat. Often, she was sent to live with her aunt or white families whom she also worked for as a maid to earn her keep. Her sole escape from these hardships were the little song and dance shows she put on for her siblings and friends in a neighbor’s basement.

So when a traveling dance troupe came to town, Josephine was immediately in awe. According to her recollections, she found her way to the manager and talked her way into the show. When the troupe left for the next town, Josephine went with them and began her career at age 13. She got her first big break in a traveling version of Shuffle Along, an all-Black musical then a huge hit on Broadway, and eventually made her way to New York City. After dancing in a few revues, New York theater types began to take notice of her, and soon a wealthy patron recruited her for a show in France.

Arriving in Paris in 1925 was a revelation. In Paris, there were none of the usual Jim Crow restrictions that had ruled her life in the South and parts of New York, where getting service at a lunch counter in the white part of town (all of Manhattan save Harlem) was unthinkable. France welcomed her with open arms. She went on to dazzle audiences, first in La Revue Nègre, and later in the Folies Bergère, with her lightning fast dance moves and a splash of her signature slapstick humor. And who could forget her “danse sauvage” in nothing but a string of beads and a skirt made of bananas? Her fame quickly preceded her, and Parisians in the know began referring to her simply as “La Baker.” The one and only.

Before too long, Josephine could hardly fathom the idea of leaving Paris. “I can’t describe what a wrench that was for me. Here, for the first time, I had truly felt alive,” she writes in her memoir. “I had plotted to leave St. Louis, I had longed to leave New York; I yearned to remain in Paris. I loved everything about the city. It moved me as profoundly as a man moves a woman. Why must I take trains and boats that would carry me far from the friendly faces, the misty Seine, the colorful quays, hilly Montmartre, the Eiffel Tower, which seemed constantly ready to kick up a leg?” Staying in Paris was the path of least resistance, and stay she did. In fact, her family didn’t see her again for 14 years, though the checks she sent home kept arriving in bigger and bigger denominations.

When I first read about Josephine Baker’s career, I saw many parallels to Anna May’s (except that the racism Josephine experienced was more menacing and ever-present). Josephine had many European suitors; she married several times; bought a chateau and adopted 12 children of many different racial backgrounds—her “rainbow tribe,” as she called them. Eventually, she brought her family over to France, rather than move back to America.

In some ways, her life reads to me as a “what if” scenario, the road not taken. I occasionally find myself pondering, what if Anna May had followed Josephine’s lead and married one of her many European beaus? What if she had ignored the pull of the Wong clan back in Los Angeles and lived the rest of her life in London, where she was adored by the public and respected by the British film industry?

It’s not known whether Anna May ever met Josephine Baker, though they certainly knew many people in common and must have been aware of each other. Shirley J. Lim has also brought to light the fact that AMW attended one of Josephine’s shows, La Joie de Paris, at the Casino de Paris in 1933. AMW’s playbill from that show is part of a collection held at the New York Public Library; however, unlike many of the other playbills there, which contain autographs from the principal performers—evidence of AMW’s schmoozing backstage with fellow performers—Josephine’s signature is absent.

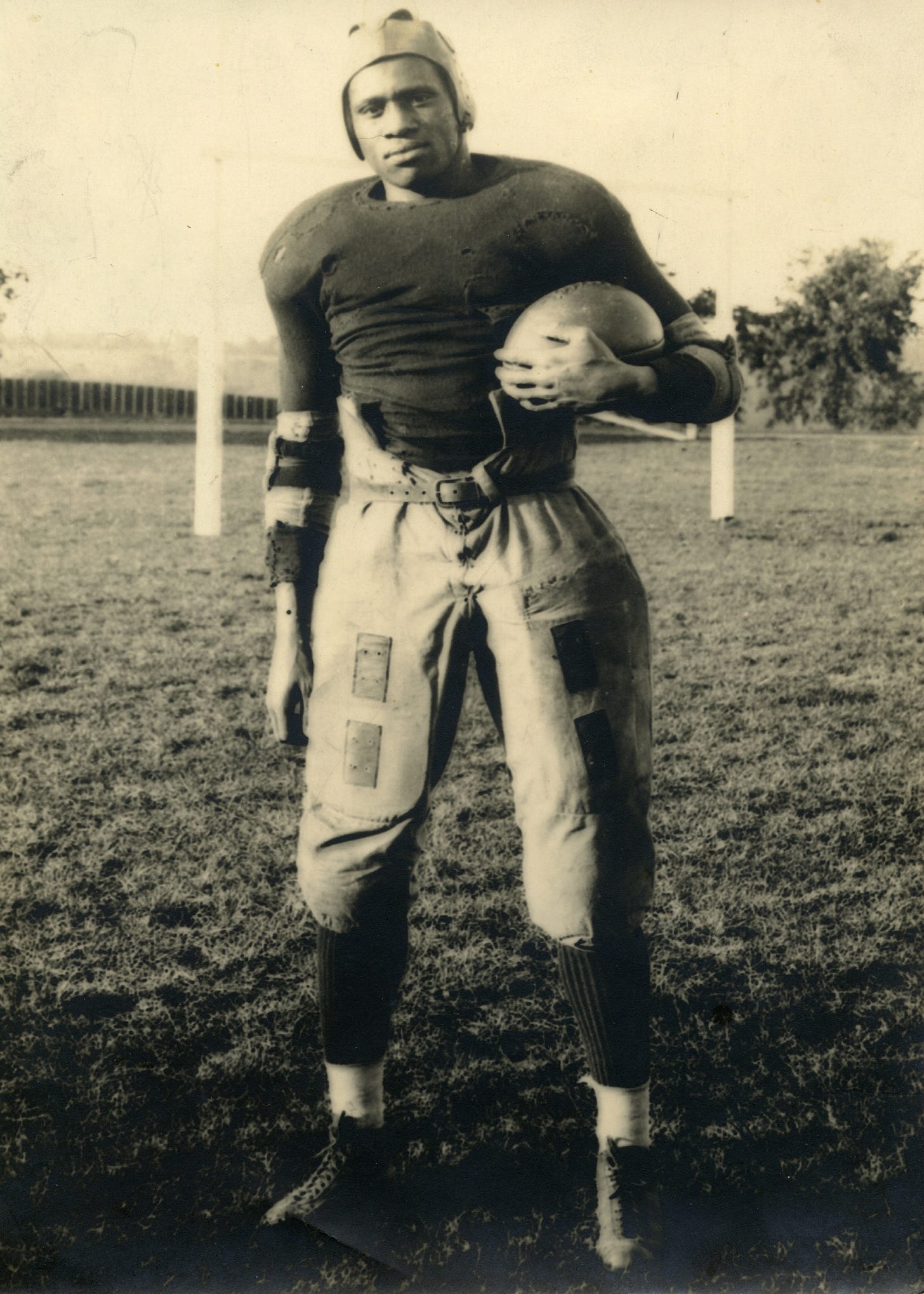

Paul Robeson, like Josephine Baker, started off from humble beginnings. Born in Princeton, New Jersey in 1898, his mother was from a prominent Black Quaker family, while his father was a formerly enslaved man who fled his captors in North Carolina at age 15. Although Princeton was technically in the North, the town was a “strictly Jim Crow place.” A place where Black children were sometimes taunted on their walk home by white kids yelling the n-word at them.

Reverend Robeson, as many called Paul’s father, was a well-known and respected pastor in the community. This direct link to the church grounded Paul’s childhood and his worldview. Indeed, the church was where he first became known for singing Black spirituals in his resonant, bass-baritone. Reverend Robeson held high expectations for all of his children, which meant they were not only expected to be upstanding citizens, but also to excel in everything else they did. Paul met his father’s expectations and then some.

When he landed at Rutgers University in 1915 he was the third Black student to matriculate in the 149-year history of the institution. Though he was well-liked, hailed an All-American athlete and star football player, and elected class valedictorian, Paul still suffered the same racial exclusions and indignities that most Black Americans were subjected to at that time. For example, he was denied from attending social dances with the rest of his class and could not travel with various college groups because hotels refused to accommodate Black travelers.

And yet Paul continued to impress everyone he met, especially white folks. His path to becoming a performer was not direct or preordained. After Rutgers, he moved on to law school at Columbia University, but continued giving private concerts to supplement his income. Eslanda Cardozo Goode, Paul’s fiancé and later wife, encouraged his theatrical career, which led him to take on roles in shows like Shuffle Along and Taboo. It was after graduating law school and starting a job at a local firm that Paul finally realized he’d never be able to achieve the career he envisioned for himself in the legal field. The company stenographer told him flat out that she would never take dictation from a n——.

So, Paul Robeson abandoned law for the theater. His roles in two plays by Eugene O’Neill, All God’s Chillun Got Wings and The Emperor Jones, at the Provincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village set the theater world afire. And just like Josephine Baker, it wasn’t long before London came calling and he signed on to open a new production of The Emperor Jones. As it turned out, the Britons loved him, and he was paid so well, he could afford a comfortable Victorian house in St. John’s Wood, along with servants to polish the silver. Naturally, he spent the next decade and a half in England.

Anna May arrived in London in the summer of 1928, right as Paul was finishing up a triumphant run in the musical Showboat, in which he played a dock worker who sings a soulful rendition of “Ol’ Man River.” As I speculate in my book, the two performers likely met at a cocktail party thrown in honor of Carl Van Vechten and Fania Marinoff, two of Paul’s earliest supporters. A kinship formed between Paul and Anna May. And although we know precious few details about their friendship—Paul Robeson’s papers remain mostly private—it’s clear to me that they held a mutual admiration for one another.

In Paul, Anna May saw a comrade-in-arms, another American who was fighting for recognition as an entertainer of color and as a human being. She understood the importance of Paul’s career and that every boundary he crossed was another step in the march towards racial equality. That’s why Anna May was there in the audience the night he took the stage as Othello at the Savoy Theatre for the very first time in 1930. And why she made a notable appearance at Paul’s 46th birthday celebrations in 1944. I hope that one day their personal correspondence surfaces, so that we can gain access to the private thoughts, fears, and frustrations they likely confided in one another. Perhaps that will be work for a future biographer to tackle one day.

Josephine Baker, Paul Robeson, and Anna May Wong all found refuge in Europe during the 1920s and 30s. Far from the oppressive limitations of America’s racial hierarchy, they discovered a newfound freedom in France and England respectively, where they could perfect their art and finally receive the recognition they deserved. Europe made them international stars and marked them as forces that even America would have to reckon with.

But, as I write in Not Your China Doll, “to say that a person of color was not at all aware of their race in Europe was a stretch. The European public’s positive reception of [these three entertainers] was merely the flip side of the coin. Where Americans saw uppity and inferior social climbers who refused to stay in their places, Europeans saw rare creatures of beauty, like a white tiger admired from behind bars at the Berlin Zoo. They were novelties, too strange—too unfamiliar—to be scorned.”

Baker, Robeson, and Wong left the United States because they had to. It was a matter of survival, really. It was the only way they could become the artists they were meant to be. This reality is underscored by what happened when each of them returned home.

Josephine Baker remained in Europe and Northern Africa throughout WWII; having renounced her American citizenship, she proved her loyalty to her adopted country by spying for the French Resistance. She came back to tour the U.S. in 1951, beginning at the Copa Cabana in Miami. Her one condition was that she would only perform at venues that allowed Black people to attend alongside their white peers, which is how she single-handedly integrated theaters across the country. The NAACP named May 20th “Josephine Baker Day” and organized a parade of 100,000 strong in Harlem to celebrate her activism.

In spite of these hard-won advances, racism persisted. That same year friends invited her to dine with them at Manhattan’s famed Stork Club, but after waiting an hour for her food—she was told they were out of crab and steak—she realized her dinner was never coming. The Stork Club simply refused to serve a Black customer. Across the room, Walter Winchell, the famous radio journalist who publicly supported civil rights, sat at a nearby table, pretending he’d never met Josephine.

Anna May Wong was initially embraced by Hollywood upon her return in 1931 and signed by Paramount to a two-picture deal. Unsurprisingly, the hackneyed melodrama of Daughter of the Dragon, AMW’s first leading role in a Hollywood film since The Toll of the Sea in 1922, didn’t perform quite as well as the studio had hoped and her contract lapsed at the end of the year. She didn’t catch one lousy break in 1932 and watched nearly every Asian role go to other actresses, usually white women who required hours of yellowface makeup.

By 1933, she had ditched Hollywood again and was on her way back to England to tour an original cabaret act of her own devising; she subsequently starred in several British film productions. Anna May eventually won another contract with Paramount in the late 1930s and exerted her influence over these films in ways she never had before, depicting positive Chinese characters on-screen. But the fact that she lost the lead role in The Good Earth (1937) to German actress Luise Rainer continued to overshadow the gains she achieved in her later career.

Paul Robeson returned to the U.S. with his family after the outbreak of WWII in Europe. Over the years he had appeared in a number of films made in Europe and the U.S., but following a part in Tales from Manhattan (1942), Paul said he was done making films because of the demeaning roles he was made to play. He became increasingly political and began to see the ways in which the oppression of Black Americans could be linked with the plight of the working classes around the globe, regardless of race. His visit to the Soviet Union in 1934 was also an important influence on his work, but it branded him a communist sympathizer in the eyes of J. Edgar Hoover, who launched a campaign to tarnish Paul’s reputation in the 1950s.

The straw that broke the camel’s back was a short speech Paul gave at the Paris Peace Congress in 1949. “We are determined to fight for peace. We do not wish to fight the Soviet Union,” he stated, according to speech notes reviewed by his biographer Martin Duberman. However, his words were mistranslated by the Associated Press and transmitted back to the U.S. as “It is unthinkable that American Negros would go to war on behalf of those who have oppressed us for generations against the Soviet Union which in one generation has lifted our people to full human dignity.”

That statement, though entirely reasonable from a 2023 point of view, created a furor back home. The House Un-American Activities Committee subpoenaed baseball player Jackie Robinson into denouncing Paul’s words, saying he did not speak on behalf of all Black people. Paul’s passport was revoked, preventing him from traveling, and all of his U.S. concerts were canceled except for one in Peekskill, New York, where white supremacists turned out and the night ended in violence. His annual income went from more than $150,000 to less than $3,000 almost overnight.

It would be 8 years before the government surrendered his passport, and while Paul did begin touring again, by then his health had greatly declined. His own country’s vendetta against him had broken something inside him. Paul’s legacy, too, has suffered because of this smear campaign. Gilbert King writes in Smithsonian magazine that, “Robeson’s name was stricken from the college All-America football teams. Newsreel footage of him was destroyed, recordings were erased and there was a clear effort in the media to avoid any mention of his name.”

Today, few people of my generation know the name Paul Robeson. The Paul Robeson Theatre at 40 Greene Avenue in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, not far from where I live, sits empty. I pass by it often and wonder whether things could have been different for him. Different for Anna May, too—whose memory has only been revived in recent years thanks to the quarter, the Barbie, and the biopic. Maybe it could have been different, but only if Paul and Anna May had forsworn their homeland in favor of another country or people that truly valued their talents.

Is it any wonder, then, that Josephine Baker’s story ends differently because she decided to live in France till the end of her days? She celebrated her 50 years in show business with an extravaganza at the Bobino in 1975. Following the show, she fell into a coma and passed away in her sleep several days later at the age of 68. That’s what you call going out with a bang. A legendary performance to end a legendary career.

In the years since, her name has never vanished from public memory. (I knew who Josephine Baker was before I’d ever heard of Anna May Wong.) In 2021, France inducted her into the Pantheon, where she is the first Black woman and the first American to be honored alongside French luminaries like Voltaire, Marie Curie, Victor Hugo, and Alexandre Dumas.

“A country is something that happens to you,” Hanif Abdurraqib writes in his chapter on Josephine Baker in A Little Devil in America, an ode to Black entertainers. “History is a series of thefts, or migrations, or escapes, and along the way, new bodies are added to a lineage. Someone finds a place where they think themselves meant to be, and they stop moving.”

And that’s exactly what I’m trying to get at. Abdurraqib says it more poetically:

I maybe find myself envious of Josephine Baker because she was unafraid to leave. She did not need a city, or a country. She made herself bigger and more desirable than anywhere she could have been or been from. It is true that to love a place is as complicated as any other relationship, romantic or platonic. Perhaps even more so. A city’s flaws can be endless, and reflect the endless flaws of the people who populate it. To attach identity to love for a place you didn’t ask to be in, and a place that was not ever and will never be “yours,” is a fool’s errand.

Updates in Brief

This month marks the third anniversary of Half-Caste Woman, a newsletter I started in January 2021, not knowing where it would lead. I’m proud to say the newsletter has grown from my personal mailing list of friends and family to 900 subscribers and counting! Thank you for sticking with me—and if you’ve been enjoying the newsletter, please share it with a friend or two who might enjoy it.

Btw, I’m looking forward to meeting many of you in person when the book and I go on tour in March. (Event details coming soon…) Until then, enjoy this beautifully animated version of the book cover!

p.s. Don’t forget to join me and Rebecca Grace Lee for our livestream next Sunday, January 21 at 12 pm EST.

Excelled, informative essay! Thanks.