When I set out to write a book about Anna May Wong, I had a specific intention in mind. I wanted to reframe the narrative around AMW’s life and career. Rather than characterize her as a tragic victim of racism and sexism—as many articles on the internet tend to do—my aim was to acknowledge her resilience and resourcefulness, and the agency she held over her own destiny in spite of the challenges she faced.

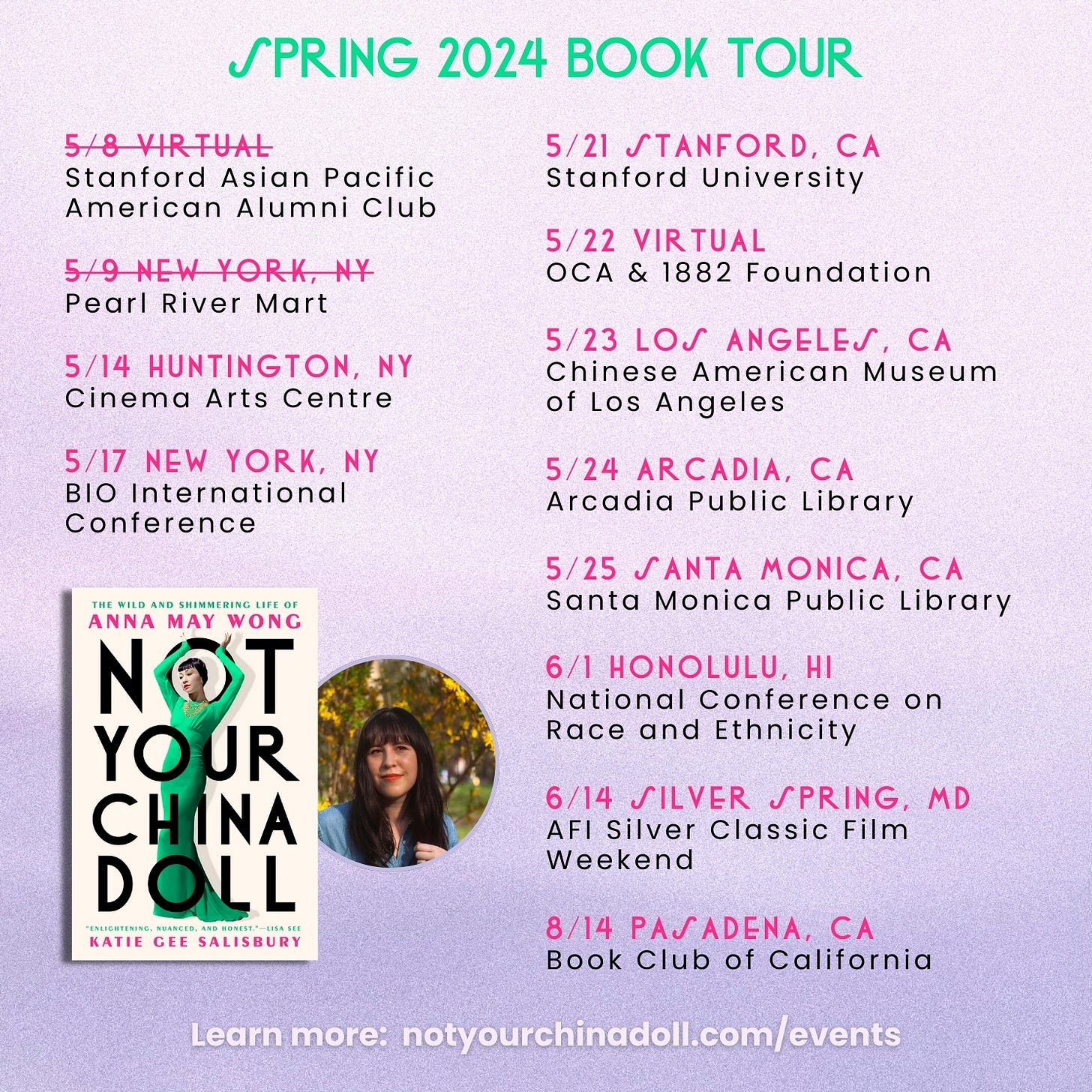

I came up with the title Not Your China Doll before I’d ever written a word of the book itself. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, the title is a riff on I Am Not Your Negro, Raoul Peck’s documentary on James Baldwin—and a reference to something James Baldwin once said. I liked turning the idea of the China doll on its head, a stereotype that Anna May Wong was so often made to play, and remolding it into a statement of defiance. No, I will not play your China doll anymore. Because I have thoughts and dreams and a voice. I will not be bound by the fantasy you project onto me.

My agent sold the book to Dutton at the beginning of March 2020. A week later the world shut down. Racked with anxiety and fear as I scrolled through the daily death counts around the world, I wondered whether anyone would even care about AMW by the time the global pandemic was over—that is, if we made it out alive.

Then, on March 16, 2020, President Trump tweeted about the “Chinese virus” and adopted terms like “Kung flu” when speaking about COVID-19. Hate crimes against Asian Americans spiked accordingly, increasing by 3200% in New York from 2019. Quarantined at home, I watched helplessly as new incidents of verbal and physical assault against Asian Americans surfaced in my social media feeds and were broadcast on television almost daily.

These attacks revealed a chilling trend; they were primarily directed at women. A catalog of the more horrific attacks still lives in my head: Asian woman punched in the face. Asian woman gets acid thrown in her face while taking out the trash. Asian woman assaulted with a hammer on the street. Asian woman followed home and stabbed to death. Asian woman pushed onto the subway tracks in front of an oncoming train. Asian woman set on fire. Six Asian women gunned down while working at Atlanta spas.

In fact, a report from National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum (NAPAWF) and Stop AAPI Hate revealed that AAPI women were twice as likely to report experiencing a targeted hate act than men. Shortly after the Atlanta spa shooting on March 16, 2021 (exactly one year after Trump’s “Chinese virus” tweet), I attended a rally to protest anti-Asian hate in Columbus Park in New York’s Chinatown. In between the speeches that day, I caught a glimpse of a woman’s homemade poster. She’d drawn a dragon and a phoenix, then written four distinct words over the illustration: Not Your China Doll.

This wouldn’t be the last time I saw the phrase on a demonstration poster. It also began popping up on social media posts from Asian American women with messages like, “I will not be fetishized, killed, or silenced.” I realized then that the phrase I’d used to describe my biography on AMW was more than just a book title. Those four words tapped into something much deeper—a common experience among Asian women everywhere. They were tired of being objectified and hypersexualized as the China doll, the plaything of men, just as Anna May Wong grew weary of playing the stereotype on-screen in the 1920s and 30s.

But what is the China doll? And where does that idea come from?

There is the literal meaning: a doll made of porcelain, sometimes called china because porcelain was first made in China. However, the term also has a more abstract, charged meaning.

In Ornamentalism, Anne Anlin Cheng posits that the “yellow woman”—a term she uses to “conjure the queasiness of this inescapably racialized and gendered figure”—is not merely objectified, but she is herself a “kind of object-person” or “a subject who lives as an object.”

“There are few figures who exemplify the beauty of abjectness more than the yellow woman,” Cheng continues, “whose condition of objectification is often the very hope for any claims she might have to value or personhood. We thus cannot talk about yellow female flesh without also engaging a history of material-aesthetic productions. The yellow woman’s history is entwined with the production and fates of silk, ceramics, celluloid, machinery, and other forms of animated objectness.”

What Cheng argues here, is that in Western society the Asian woman is only acknowledged as a person and perceived to be of value when she is beautiful, doll-like, and available to male sexual fantasies. Just as Hollywood would only grant Anna May Wong status as an actor while she was young and attractive through roles that demeaned her, either as the helpless Chinese maiden or the conniving underworld temptress.

The yellow woman, Cheng writes, “goes by many names: Celestial Lady, Lotus Blossom, Dragon Lady, Yellow Fever, Slave Girl, Geisha, Concubine, Butterfly, China Doll, Prostitute. She is carnal and delicate, hot and cold, corporeal and abstract, a full and empty signifier.” It’s not a coincidence that this list of names closely approximates the roles AMW played in her early career. Anna May was Lotus Blossom in The Toll of the Sea, the Mongol Slave in The Thief of Bagdad, Princess Butterfly in Pavement Butterfly, a high-class prostitute in Shanghai Express, and the daughter of Fu Manchu in Daughter of the Dragon, wearing a full-body dragon on her dress.

But to understand what Cheng means by the term “animated objectness,” we have to go back to the beginning, to the first Chinese woman to step foot in the United States. Her name was Afong Moy and she arrived in New York City in 1834. Very little is known about her, except for the details surrounding the circumstances of her arrival. Two traders, brothers Francis and Nathaniel G. Carne, imported Afong Moy like they would a box of tea or a bolt of silk and then set her up as an exhibition called “The Chinese Lady.” She was an attraction, a human zoo of one, advertised to bring customers in to buy the Carne brothers’ other wares, such as 600-year-old mirrors, bells, and Chinese instruments.

A few years ago I attended a performance of Lloyd Suh’s play about Afong Moy, aptly titled The Chinese Lady, at the Public Theater. The audience laughed nervously as the actor playing Afong Moy went through the motions of her one-woman show: She ate rice from a porcelain bowl using chopsticks; she poured tea into a tea cup; she stood up and walked haltingly on her tiny bound feet. Like a doll, the real Afong Moy was made to repeat this performance ad infinitum for the pleasure of her audience. The short film “Astonishing Little Feet” by Maegan Houang imagines her existence in stark relief (h/t Aimee Liu for making me aware of this film).

Thus, Cheng’s thesis is proven correct—Afong Moy, the original “yellow woman,” is only able to secure her survival through “crushing objecthood.” Indeed, like any imported object, she is placed—no, displayed—in a room “surrounded by various articles of Chinese manufacture, worthy the attention of the curious.” There is no question as to her purpose or her lack of agency. How can an object have agency?

In 1929, in a different kind of performance, Anna May Wong made her stage debut in London’s West End in an English adaptation of a Yuan-dynasty play called The Circle of Chalk. Predictably, British critics praised Anna May’s beauty and porcelain-like skin but complained that she didn’t sound Chinese enough because of her terrible American accent. I write in my book: “Maybe the English simply had a bad case of China Doll syndrome. They delighted in gazing upon Anna May Wong’s ‘enigmatic’ veneer, but once the woman inside spoke, her voice rang out like a gong, shattering the illusion that she might really be made of porcelain. The thing is, dolls are never wanted for their voices, much less their souls.”

Asian women in the realm of the real, not the theoretical, are human beings, not dolls. For me, taking back control began by changing the narrative around what someone like Anna May Wong was and should be. There are many who continue to see her as a doll, a “goddess” to worship but also objectify, a fantasy woman to sexualize through unsubstantiated rumors of her sex life.

I never saw her that way. Because she reminded me of my mother, my aunts, my grandmother, my girlfriends and classmates, my teachers and mentors, and finally, myself. And we are none of us dolls.

When I began to share the title of my book with other Asian American women, many responded with an unexpected verve. “I love that title!” they’d say, as if ready to pump their fists in the air. They got it so completely, it took me by surprise. I now realize that writing a biography of Anna May Wong was about so much more than simply telling one woman’s story; it was also a way of telling a collective story about the everyday provocations that come with being an Asian American woman.

This is a wonderful post, Katie! It reminded me to share this gorgeous and mesmerizing short film about Afong Moy: https://www.nowness.asia/series/nowness-shorts/astonishing-little-feet by Director Maegan Houang . Thank you for your dedication to this history and to AMW!

I so agree with your statement. i admire you for presenting this, agree with you and most of all thank you being you!