The Wrong Wong

did Anna May Wong’s sister appear in The Good Earth?

A quick note before we jump into this month’s essay: I want to give a hearty thanks to everyone who has bought a copy of Not Your China Doll and come to one of my events over the last few months. It has been such a joy getting to meet you in person and share our mutual admiration for Anna May Wong! If you’re looking for more ways to support the book and AMW’s legacy, here are a few other actions you can take:

Write a review on Goodreads or Amazon (or copy/paste to both!)

Recommend the book the next time someone asks you for a reading rec. Word of mouth is still the most powerful tool for selling books.

Take a photo of yourself with the book, post it to Instagram/Facebook/Twitter, and tag me!

Buy a copy for someone you love. A limited number of signed copies are available at Greedy Reads, Larry Edmunds Bookshop, the gift shop at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, and elsewhere.

Thank you again for reading! And now, without further ado…

In this era of constant change where everything seems disposable, books remain one of the few objects of permanence in our society. But what happens when a book is printed with mistakes in it? Unintended errors always get into final pages somehow, from minor typos to larger factual inaccuracies. Such is the imperfect beauty of anything made by human beings. Thankfully, there’s always the next printing. In anticipation of that, I’ve been keeping a short list of errors I’d like to submit corrections for when the next printing of Not Your China Doll goes to press.

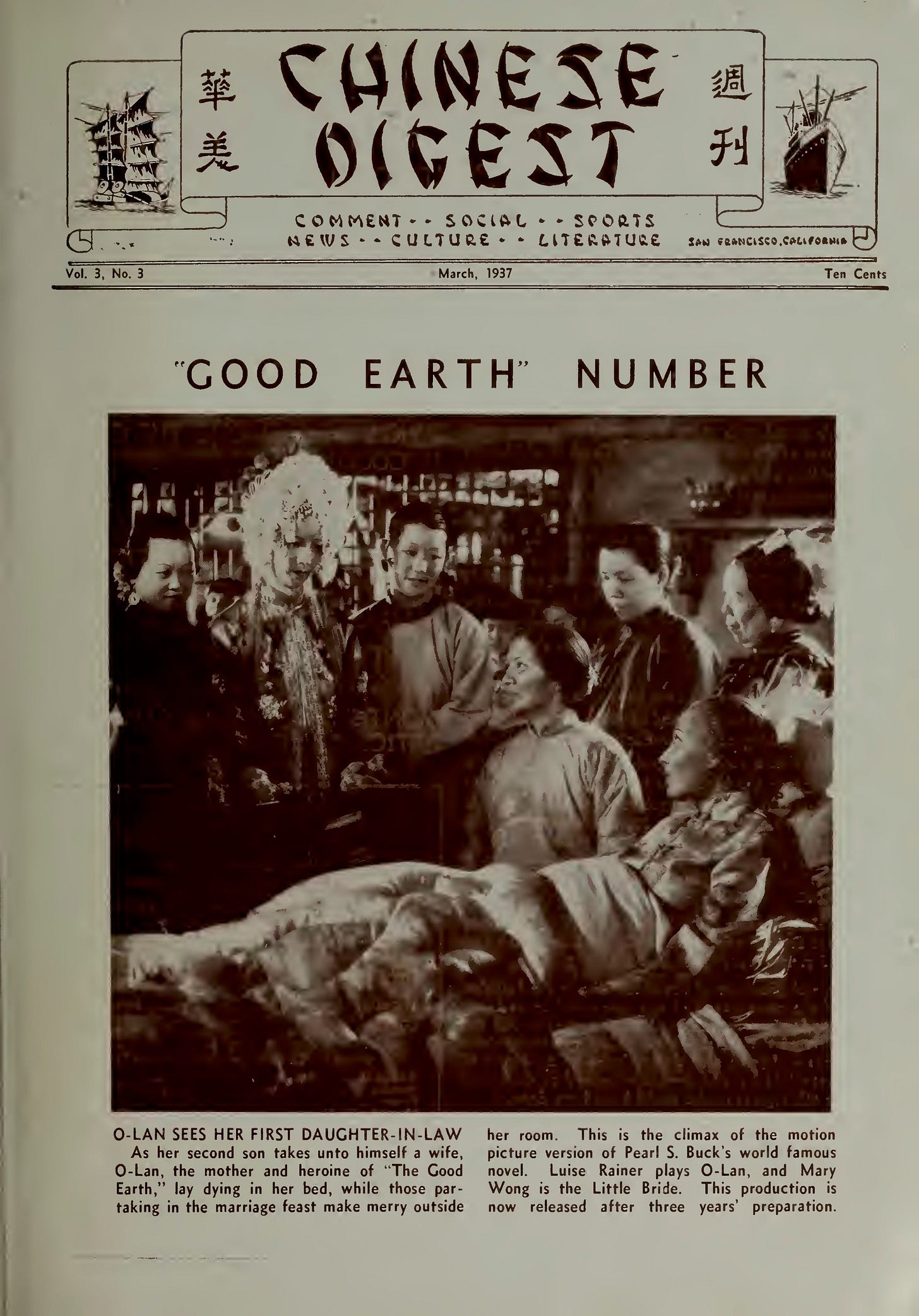

One quandary that I’ve been turning over in the back of my mind is the long-touted claim that Anna May Wong’s younger sister, Mary Wong, appeared in The Good Earth as “the Little Bride.” The film famously passed over Anna May for the female lead and gave it instead to German actress Luise Rainer. The Good Earth was among one of the first Hollywood films to present a sympathetic image of the Chinese. Based on the best-selling book by Pearl S. Buck, the script tells the epic tale of Wang Lung and O-lan, humble peasant farmers who must overcome drought, famine, war, and pest in order to survive. Despite MGM’s efforts to stage an “authentic” portrait of China, the principal roles were all given to white actors who played the Chinese characters in yellowface makeup.

As for AMW, she ultimately rejected the paltry secondary role MGM offered her and decided to take her first trip to China instead. If it was true that Mary played the Little Bride who marries Wang Lung’s first son, it always struck me as odd that Anna May herself never mentioned this detail publicly.

I would think that Anna May—even knowing the rancor she felt toward MGM—would have been happy to support her sister winning a credited role in such a big Hollywood production. AMW was always trying to launch her brothers and sisters into their own film careers. At one time or another, nearly all her siblings had aided her on-screen profession in some capacity. James reviewed the script for Shanghai Express and suggested edits. Frank did a stint as AMW’s chauffeur. Several of the Wongs and even her father were allegedly recruited as extras in films like Mr. Wu and Old San Francisco.

Similarly, her eldest sister Lulu, who early on served as a kind of manager and secretary, later spent 9 months on location in Alaska shooting the film Eskimo. In an interview with Louella Parsons, Anna May seemed to hedge her own interest in winning the lead role of O-lan by suggesting, “[Lulu] is the logical person for the wife in ‘Good Earth.’ She has been a mother to us all, although she isn’t much older than we are.”

By the late 1930s, when AMW was making her series of crime thrillers at Paramount, Mary was employed as her stand-in. Several behind-the-scenes photos of the sisters on set attest to this. So it seems plausible that Mary might have also taken a role in The Good Earth—a film that, according to William Gow, employed about one in three Chinese Americans living in Los Angeles at the time.

Besides, all of AMW’s previous biographers claim this as fact. Anthony B. Chan, Graham Russell Gao Hodges, Shirley J. Lim, and Yunte Huang each assert that it was Mary Wong, Anna May’s sister, who played the Little Bride. And so, I went along with them and made the same claim in my book.

But the question lingered. Was it possible that I had the wrong Mary Wong? Just because something is printed in a book, doesn’t mean it’s true. As I have written in the past here and here, mistaking one Asian person for another Asian, i.e. the “Wrong Asian,” is a pernicious and constant phenomenon. Could I have made the same basic blunder? Was I also guilty of calling out the wrong Asian?

The first crack in the wall appeared when I tried to compare pictures of Mary Wong with publicity stills of the woman who played the Little Bride. The problem is that damn bridal headdress! One newspaper account reported that the headdress “took 30 women three months to fashion it, carefully stitching to it the thousands of pearls and jewels.” With all the silk, lace, beads hanging down from her crown, it’s hard to get a clear look at her face. That and the low-quality photo reproductions make it impossible to distinguish her features.

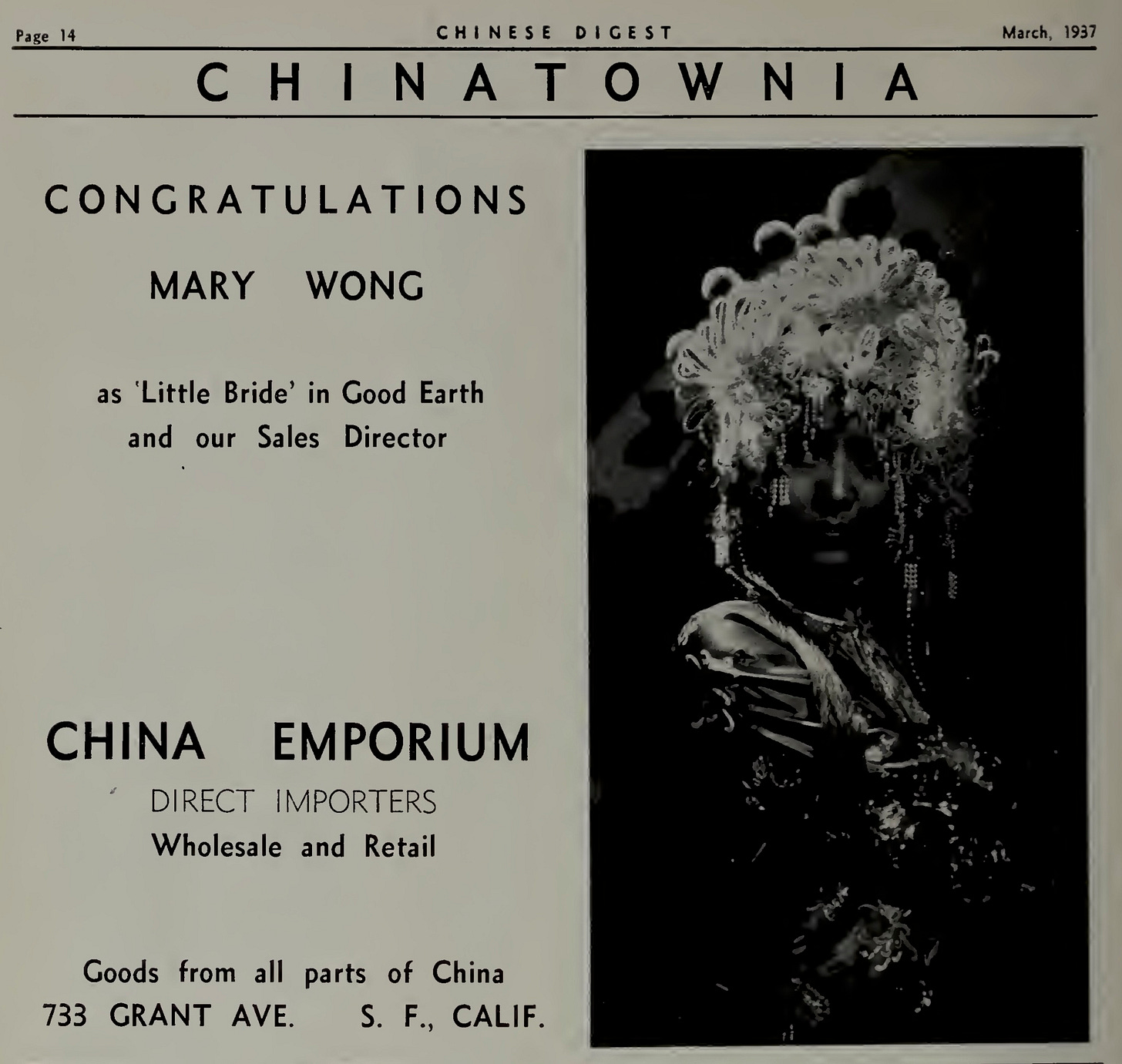

Then there is the ad in the special Good Earth edition of Chinese Digest. In it, Mary’s supposed co-workers at the China Emporium in San Francisco congratulate her on her role in the film. I’d never seen any other evidence that Mary had moved to SF to work at this business, but it was within the realm of plausibility.

The thing I really should have paid more attention to, however, was a different picture in that same March 1937 issue of Chinese Digest. Although most of the principal roles in The Good Earth were filled with white actors, a number of smaller and supporting parts were given to Chinese Americans, many of whom were recruited when MGM staged local auditions up and down the West Coast. The Good Earth was far from being a perfect—or even good—representation of Chinese people, but it at least represented progress from the evil supervillain and dragon lady stereotypes that still colored many imaginations. Thus, the Chinese American community had reason to celebrate the film and the community members who contributed to its production.

Here, the Chinese American cast is gathered in a lineup and highlighted for their achievement. Though I had seen this photo several times (Aimee Liu also refers to it in her Substack; her aunt, Lotus Liu, is one of the cast members), I’d never really reckoned with it.

On first glance, none of the people pictured looks like the Mary Wong related to AMW. Yet, Mary Wong is noted as standing fourth from the left. Again, the photo is washed out and grainy, but the woman doesn’t look like AMW’s sister. She looks older and seems to be wearing heavy eye makeup. The accompanying article provides short bios for each of the players, but Mary’s bio doesn’t point to anything conclusive one way or the other. It simply says:

Mary Wong is the prettiest Chinese girl appearing in “The Good Earth.” In San Francisco she is a buyer and an expert sales manager at the China Emporium, of which she has a partnership. In “The Good Earth” she radiated so much charm as the Little Bride that no cutting of even an inch from her acting was possible without removing something of the uniqueness from the picture. However, they had to make her speechless for the simple reason that Chinese brides are supposed to be seen but not heard. “That’s the most difficult thing for me to do—remaining silent,” said Mary, afterward.

There it is again. The glaring omission of whether Mary Wong is related to Anna May Wong. Was the situation so publicly painful that no one wanted to mention they were sisters and embarrass AMW yet again for her lack of involvement in the film? Or was something else at work here? At the very least, I should have checked into the China Emporium gig, tried to see if I could find any other records to corroborate AMW’s sister moving up to SF. But with a looming deadline and many other essential facts left to fact check, I let this one slide.

Many months later, on the eve of Not Your China Doll’s publication, it finally occurred to me. If I wanted to know whether Mary Wong was indeed the same Mary Wong who played the Little Bride, all I had to do was check her Chinese Exclusion files, which would tell me whether she was even in the country at the time the film was being made.

This was the other piece of the puzzle that had been nagging at me. International travel was slow and planned out far in advance in the 1930s. I knew that Mary had traveled with the rest of the Wong clan (minus AMW) to China in 1934, but I didn’t know when she returned from that trip. I also knew that she had to flee China in late 1937 when war broke out with Japan—this was a source of great anxiety for Anna May. She was tied up in knots until all of her family safely returned from China to the United States.

The Good Earth was shot on the MGM lot and a massive 5-acre farm set in the San Fernando Valley during most of 1936. If Mary was in the film, would she have gone directly back to China at the end of 1936 and then returned to the U.S. within less than a year? The timing didn’t quite make sense. The other possibility was that she had never left China and stayed there continuously from 1934 to 1937.

Well, it turns out the Chinese Exclusion Act was good for something. Because it mandated the government track all Chinese residents, whether resident aliens or citizens, we have a record of when Mary exited and reentered the country. She only applied to leave the country 3 times. The first was in 1925, when she traveled across the border to Mexico with the rest of her siblings to establish their identity papers. The second time was in 1933 when she applied for a trip to China; however, her plans changed and the application was withdrawn. And then finally in August 1934, when she actually sailed for China with her father, Lulu, Frank, and Richard. Her records denote no other exits or reentries until November 1937 when she returned from war-torn China.

Mary Wong, sister of Anna May Wong, couldn’t be the actress in The Good Earth because she was in China the whole time the film was being made. The smoking gun had been staring me in the face all along. If only I had examined Mary’s Chinese Exclusion files sooner!

Of course, now that I saw my error, I had to know—who, then, was the Mary Wong who played the Little Bride?

Mary Wong is a fairly common name, so I thought it might be difficult to pinpoint the right one. (In fact, AMW herself was once mixed up with a Mary Wong from New York.) But all it took was a few targeted searches on Newspapers.com to narrow it down.

The other Mary Wong was from Lodi, a farming town in California’s Central Valley known for its wine production. Although she had relocated to San Francisco after marrying Andrew Sue, the local papers were quick to applaud their hometown girl. “Former Lodi Girl Is Given Job in Films” the Lodi News-Sentinel proclaimed. According to a report in the Los Angeles Times, General Tu (the Chinese Nationalist Government’s consultant on The Good Earth) and Paul Muni (cast in the lead role of Wang Lung) discovered Mary while she was working at the China Emporium. The article goes on to describe her as “a descendant of a pioneer Chinese family of Amador county.”

In the days leading up to The Good Earth’s 1937 premiere, the Lodi News-Sentinel ran a profile of Mary Wong on the front page, singing her praises. “The girl who once played on the streets of Lodi, after six years of playing extra ‘bit’ parts in the movies, enters into her own in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s version of one family’s story in China.” The writer goes on to claim that Mary would have played the lead role of O-lan had it not been for the fact that she was taller than Paul Muni and “she didn’t look Oriental enough!”

Clearly, it meant a lot for the Chinese American community in Lodi to see one of their own ascend to the silver screen in such an important production. Susie Y. Wong, Mary’s sister, was the well-known owner of a Chinese restaurant in town, which served as a de facto shrine to the film and her sister’s contribution to it.

Over at the King Yin Cafe, [Mary’s] friends, relatives and admirers are looking forward to seeing “Good Earth.” Until then they have scores of framed photographs—of Paul Muni, of Louise Rainer, of Walter Connoly—of all who had a part in the creation of the picture and whose words of praise for Mary reflect the esteem in which the Lodian is held.

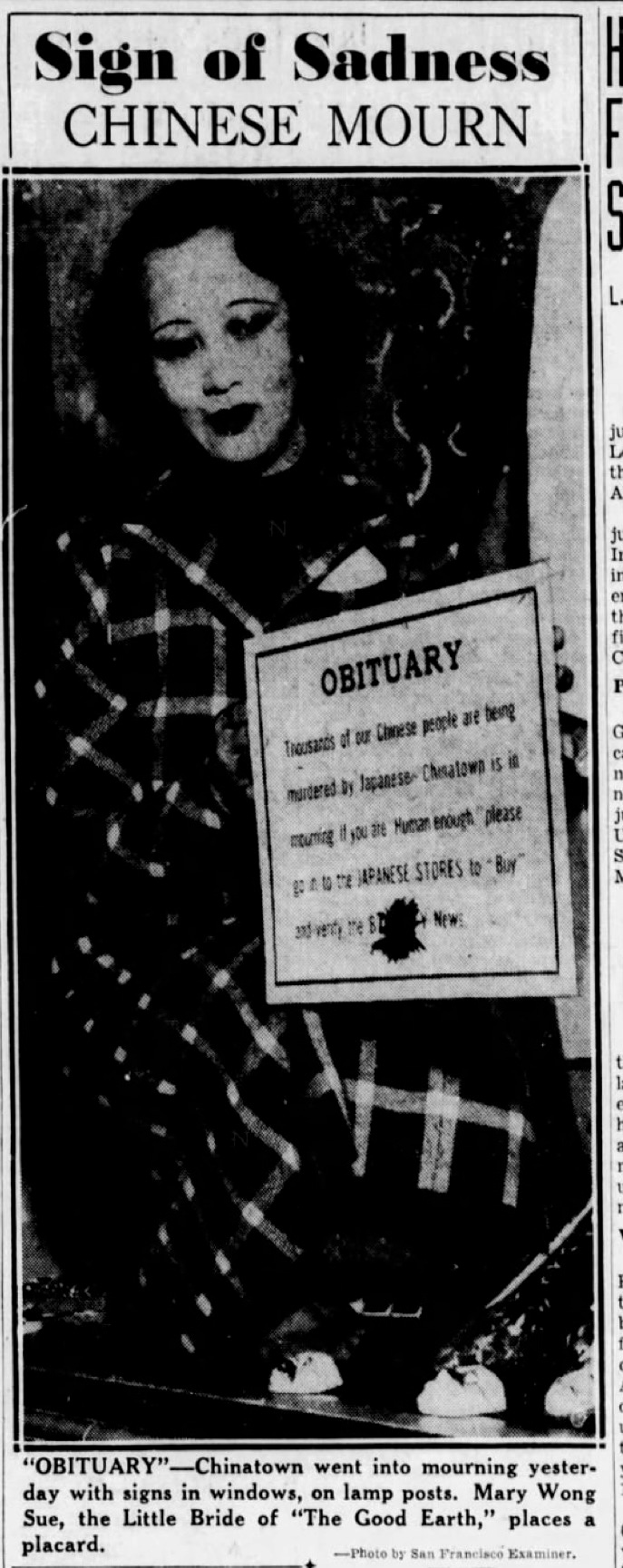

Later that year, Mary Wong from Lodi was invited to preside as queen over the Chinese Association float in the Lodi Grape and Wine Festival parade. But as far as I can tell, she didn’t continue with her acting career and returned to her job at the China Emporium in SF. This clipping shows her putting up an anti-Japanese poster in one of the store’s windows in support of China during wartime. Meanwhile, Mary Wong, sister to Anna May Wong, was caught in the crosshairs of that very war, still two months away from arriving safely back in the U.S.

There is both relief and a kind of euphoria that comes with solving a research mystery like this one. I hate that I got it wrong in the book and am eager to have it corrected for the next printing, but this experience of checking and rechecking my own work (and the work of those who have written about AMW before me) has been a welcome reminder: Question everything.

Amazing detective work!

It might seem, initially, that the issue of whether Mary Wong actually performed in "The Good Earth" is tangential-a segue. But, in Wong's life, it appears correcting small mistakes uncovers larger ones, or exposes outright falsehoods.

What I appreciate about this blog is that it establishes that the story is not complete, and I can foresee a second, expanded and revised version of the bio.

The author does not accept her book or Wong's life as something static, a "done deal". There's more to tell.

Good job, Katie.