Trigger Warning: This issue discusses the practice of yellowface and contains images of white actors impersonating Asian characters.

When the topic of yellowface is broached, most Asian Americans can readily call up the insulting images of Mickey Rooney as Mr. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) or David Carradine as Kwai Chang Caine (a role that was originally pitched by and for Bruce Lee) in the TV series Kung Fu (1972). But this demeaning practice has been around for much longer than the 1960s.

Just as blackface was established in the 1830s as America’s first national entertainment, yellowface has been part and parcel of the film industry for more than a century. In the early days of the cinema, playing a “screen Oriental” was practically a rite of passage for most Hollywood starlets. Mary Pickford, Norma Talmadge, Alla Nazimova, Pola Negri, Bessie Love, and Laska Winter (who I once mistakenly thought was Asian) all had stints putting on the yellow mask.

Myrna Loy got her start in Hollywood by playing “exotica.” Leading ladies were narrowly defined as blonde and blue-eyed beauties back then. Loy was a freckled redhead from Montana and producers didn’t quite know what to do with her, as she later explained in an interview for the Columbia University Oral History Project. Then she got a part in a Natacha Rambova vehicle called What Price Beauty? (1925) as a bewitching, ethnicized vamp and the type seemed to stick.

“With the structure around my eyes, it turned out, makeup could make me look Oriental,” Loy wrote in her autobiography. “They just whitened my upper lids, accented the natural line, and I got away with it. So what do they do back at Warners? They cast me as a Chinese in The Crimson City, with Anna May Wong. Up against her, of course, I looked about as Chinese as Raggedy Ann.”

Even Loy’s stage name—her real name being Myrna Williams—was crafted in a way to insinuate that she could be more than just white. “Some felt for a time that possibly I had some Oriental blood,” Loy confessed. “How nice that would be, but however, it doesn’t happen to be true. I’m Welsh, Scotch and Swedish.”

For years, Loy was typecast in “Oriental villainess” roles like the one she played in The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932) as the super villain’s daughter. “Interviewers often assume that I had a miserable time playing all those evil creatures, all those women with knives in their teeth,” Loy recalled. “Not at all. I can’t say that things came easily—it took a long, long time to find my real niche—but those roles were fun to play, despite their unreality. The characters were always so nefarious that they had to die at the end.”

It was easy for Loy to dismiss the “unreality” of the parts she played in yellowface because she got to take off her mask at the end of the day. Eventually she shed these exoticized roles entirely and found success in film noir scenarios like The Thin Man (1934). Meanwhile, Anna May Wong continued being typecast as the Asian vamp; the idea that she could play a character who was not defined by her race never seemed to occur to the studios. AMW got so fed up with it, she left Hollywood in 1928 to make films in Europe.

What makes yellowface so insidious—beyond the mere disrespect of caricaturing people who are perceived as different—is that it props up white supremacy. As Columbia professor Sharon Marcus explains in her book The Drama of Celebrity, “dominant groups deny subordinated groups agency by depicting them as mere mimics.” In other words, in a society where whites are assumed to be superior to nonwhites, the former have the right to imitate and mock others as a way of maintaining their superiority. Racial parody, then, is inherently racist because the power to imitate others only flows in one direction, from the top of the white racial hierarchy to the bottom. Which is how you get bizarre arrangements of white actors playing Asians and Blacks, Latino actors playing Arabs, Chinese actors like AMW playing Native Americans. But nonwhites imitating whites? Strictly off-limits.

This was made patently clear to me when I stumbled upon an article in Screenland about Mexican actress Dolores Del Río’s starring role in Evangeline (1929), a love story between French settlers in Nova Scotia. “A good many people have been antagonistic toward the thought of Dolores Del Rio, a Mexican girl, playing Evangeline,” reporter Helen Ludlam noted. “To some extent I shared this feeling, until I saw Dolores do a scene or two and talked with her and her co-workers. After all, they selected Renee Adoree, a French girl, to play a Chinese heroine when Anna May Wong, as fine an actress as there is on the screen, was unavailable.”

The reporter continues, as if reflecting on Hollywood’s hypocrisy for the first time: “And we have had American girls playing Orientals and Latin types, so it does seem a little inconsistent to turn squeamish at the thought of a Mexican girl playing a French Canadian. According to Longfellow, Evangeline’s hair and eyes were dark, and I don’t think her skin could have been much fairer than that of Dolores. And after all, it is the understanding of the part that matters most and the player’s ability and training as an actress. And Dolores Del Rio is a real artist.” The role of Evangeline was not a caricature or meant to be demeaning in any way, but Del Río’s Mexican background was still enough to turn a few “squeamish” at the thought of her romancing a white man.

Also, Anna May was available for the film the reporter referenced, Mr. Wu (1927). Renée Adorée was cast as Mr. Wu’s daughter, while AMW merely played a supporting role.

Any number of reasons have been cited for the pervasive use of yellowface in Hollywood. There’s the old line about not being able to find Asian actors who are up to snuff (as you’ve read in the pages of Half-Caste Woman, there were plenty of Asians in the industry but producers weren’t willing to give them a chance the way they did white actors). Or there’s the idea that Asian actors don’t sell at the box office, that American moviegoers don’t want to see Asians in lead roles—even when the character is supposed to be Asian!

Perhaps the most persistent excuse used to reject actors of color from leading roles is the fear of racial mixing, that ugly, 13-letter word miscegenation. Studios claimed it would be improper to depict people of different races in romantic relationships since interracial marriage was then illegal in America. Even so, stories about breaking this unspoken taboo were popular and made for juicy melodrama, which meant Hollywood sometimes broke its own rules (see Dolores Del Río above).

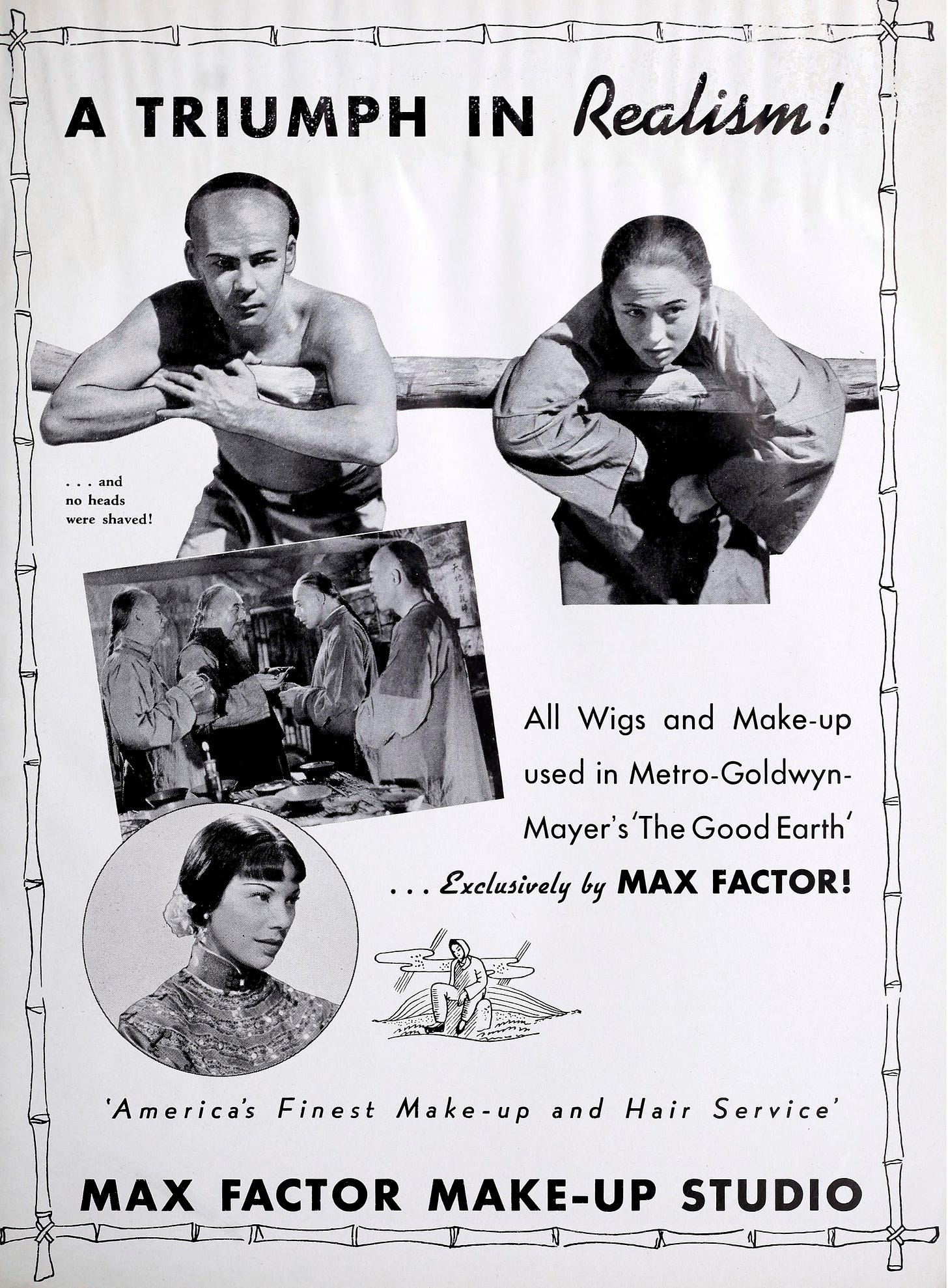

Eventually, a list of “do’s and don’ts” were codified into the Motion Picture Production Code, more commonly referred to as the Hays Code, and strictly enforced from 1934 onwards. MGM happily hid behind the Hays Code, saying it prohibited them from casting AMW as the female lead in The Good Earth (1937), a film about Chinese peasant farmers, because white actor Paul Muni was already set to play the Chinese husband. The studio failed to mention that producer Irving Thalberg just didn’t see AMW as a fit for the role, which would have been harder to explain away in the press—she was the only major Chinese American actress and O-lan was a part that called for exactly that.

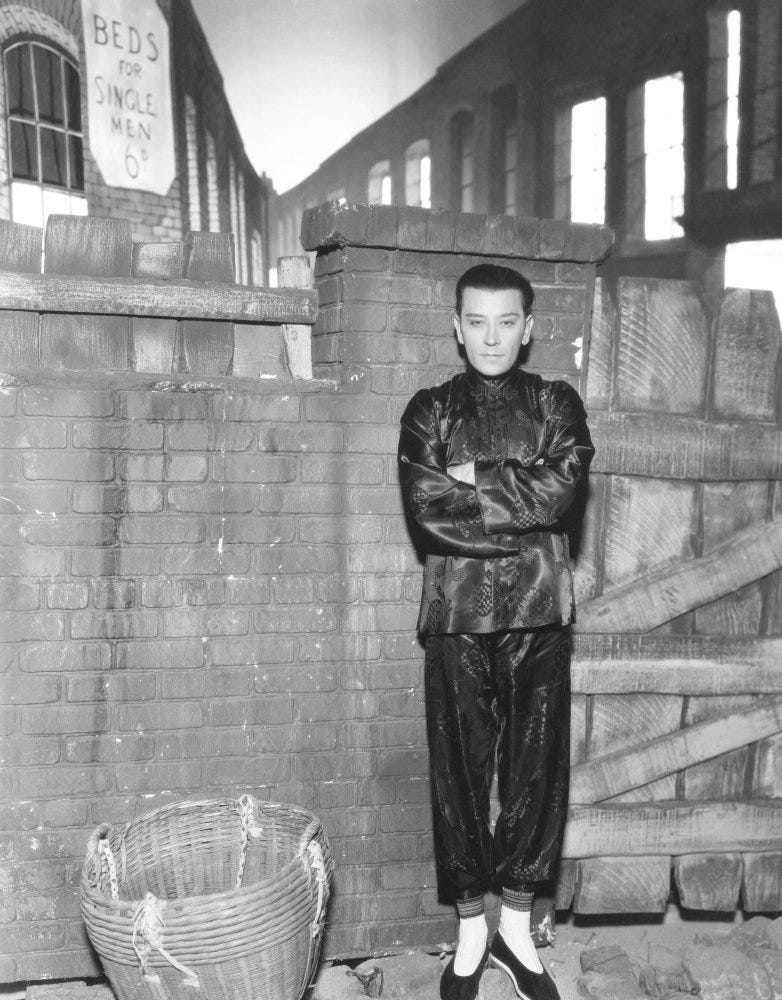

As if this illogical line of reasoning weren’t bad enough, the actual application of yellowface in the makeup room was highly impractical and ineffective. Actors had to spend hours in the makeup chair every day to don the yellowface. After all that, most barely looked the part. When I read about the lengths Swedish actor Nils Asther went to in order to impersonate the Chinese warlord in Frank Capra’s The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1932), I couldn’t help but laugh at the absurdity, the endemic racism of barring actors of color from playing themselves.

Making Up Is Task For Nils Asther

The transformation of an amiable young Swede into a suave and rather sinister Chinese gentleman is a process requiring three hours of the time and art of Norbert Myles and as much of patient discomfort on the part of Nils Asther.

Myles is Columbia’s make-up artist, and Asther is the romantically restrained her of “The Bitter Tea of General Yen”—a job of acting which, considering the July and August weather in which it will be done, and the quantity of make-up, is not one to be envied. Especially not since movies never allow orientals to get the girl, in this case Barbara Stanwyck.

Besides having his lashes trimmed and his eyebrows plucked, his eyes slanted with tape (try that some time) and his face covered with special make-up paste, he loses most of his hair to have it replaced by straight locks becoming of a Chinese.

Hard Work for Him

The picture will be five weeks in production, with Nils working practically every day. That means little sleep—he’ll have to report at 6 a.m. to be ready for the set at nine.

Asther, joining that other Swede, Warner Oland, as portrayer of oriental roles, is the first in a long time to play a romantic easterner. Most of the actors who are painted as Chinese are character players, like Edward G. Robinson. Richard Barthelmess twice has enacted Chinese roles—first in “Broken Blossoms” and then in “Son of the Gods.” In the latter he turns out to be really caucasian, and wins the girl. Asther wins only—death. But he’ll get new fans too.

(La Crosse Tribune, Aug. 1, 1932)

I guess that’s the price you have to pay to be yellow, or at least to pretend to be, anyway.

Not surprisingly, George Raft, who played a half Chinese, half white nightclub owner in Limehouse Blues (1934) alongside AMW, did not relish his yellowface experience either. “Never again will I ask to be a Chinaman,” he later told a Hollywood reporter.

To think of the abundance of resources that went into the charade of yellowface, the wax and greasepaint, the false teeth and prosthetic eyelids, and all the while studios could have simply hired Asian actors to play Asian roles. It makes me angry, but it also makes me scoff at the sheer stupidity of it all. Hollywood wasn’t fooling anyone.

There are many things wrong with yellowface. For one thing, it kept Asian American actors like Anna May out of work. As I write in my book, 1932 was one of the worst years of AMW’s career. Although she was coming off the success of the Oscar-nominated Shanghai Express (1932), and there was a glut of China-themed movies in production (studios were eager to profit off the real-life conflict between Japan and China), AMW just couldn’t seem to land a gig. Producers preferred to cast their blonde leading ladies instead. They made the implicitly biased calculation that a Helen Hayes or a Loretta Young was a sure bet even with taped eyes and a jet-black wig.

What’s more, white actors in yellowface depicted Asians in a limited number of stereotypes: the evil dragon lady or the helpless China doll; the cruel mastermind or the stoic good samaritan; the depraved opium smoker/gambler/smuggler or the bumbling, pidgin-speaking domestic servant. At least the Asian American actors who were also cast in such roles had the opportunity to bring some dignity to their parts. Most Americans at that time had little to no exposure to Asian Americans or Asian immigrants. Exaggerated, inauthentic depictions in yellowface did much to damage the image of Asians in America and further dehumanized them as a “heathen race.”

Worst of all, few seemed to stop and consider the effect of these stereotypes on Asian Americans themselves, the people being impersonated. I’ve been obsessed with a passage in Elaine Hsieh Chou’s novel Disorientation ever since I read it months ago because it addresses this aspect of yellowface so precisely. (Btw, the novel is a hilarious sendup of academia and the ways in which yellowface is still very much in practice today.) Near the end of the book, Chou’s protagonist, Ingrid Yang, recalls how a white colleague once told her, “I know what it’s like to be you.” This sends her spiraling.

Give me a fucking break. Paint washes off. But her face wasn’t painted on. She was born with it and she would die with it.

Already she suffered from existing in a world where she was infantilized even at age thirty. Where every representation of her was one she had had no say in. She had to put up with the five-dolla-sucky-suckys and the me-love-you-long-times not through any choice of her own. She had to live with the consequences of a dead white man’s whims when he ended the story with Cio-Cio San choosing the love of a white man over her child’s life, over her own life. That burden, the consequences of these popular narratives, was hers to carry. Never to those who created them. After churning out a day’s worth of harm, they got to go home and live untouched by it. They got to be free.

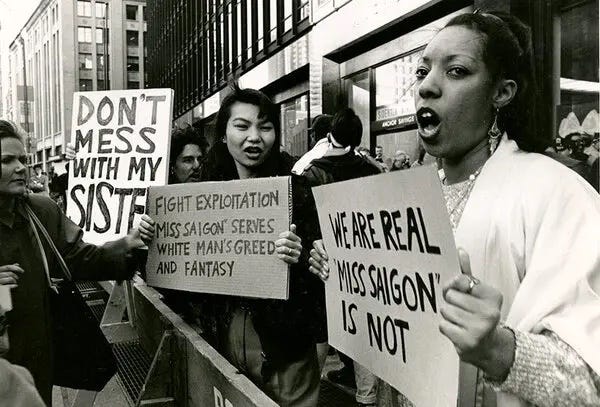

The “cancel culture” debate of our era is not really about canceling people and institutions for being “insensitive.” (And let’s be honest, those with real power are beyond cancellation.) The so-called culture war is about something much deeper and intrinsically American. It’s about who gets to be free—free to be themselves, free to exist as individuals and not as the offensive stereotypes projected onto them by others.

Yellowface, like blackface, has gone out of style, but it’s not extinct. It merely shapeshifted into “whitewashing,” a workaround whereby Hollywood studios rewrite roles originally scripted as Asian and cast white actors in them instead. There are also some who continue to defend yellowface; they claim it’s not racist, it’s just acting.

Excavating this history can be painful. But as disturbing as these images are, they serve a purpose. No good will come of relegating yellowface to the dustbins of history when we’re still living with its consequences today. If you ask me, staring down the ugly, ivory-toned ghosts of Hollywood’s racist past (and present) is the only way to build a different future.

The Newest Barbie on the Block

If you were that little girl who longed for an Asian American Barbie doll, your wish has finally been granted! Anna May Wong is the latest woman to be inducted into Barbie’s Inspiring Women series. The doll was announced on May 1 to celebrate AAPI Heritage Month and within a matter of days preorders sold out at Mattel, Walmart, and Target.

As NBC News writes, the doll “features her iconic blunt bangs, a red-and-gold dress adorned with a dragon, a sheer red cape and gold heels.” The dress is a clear homage to the one AMW wore in Limehouse Blues, which was later displayed in the Met’s China: Through the Looking Glass exhibition in 2015 and then emulated by Gemma Chan for her 2021 Met Gala look by Prabal Gurung.

With her face on the quarter and her likeness now enshrined as a Barbie, it’s safe to say that a lot more children are going to grow up looking up to Anna May Wong. And I’m here for it!

You nailed it with this article.