The Chinatown-Hollywood Connection

community histories, Chinese American extras & pushing back against stereotypes with William Gow

William Gow is a fellow traveler in the world of Asian American Hollywood history who I was lucky enough to cross paths with while I was in the midst of writing Not Your China Doll. Will is a Sacramento-based community historian, educator, and documentary filmmaker, as well as a fourth-generation Chinese American. His time serving as a volunteer historian with the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California (CHSSC) proved to be a formative moment in his career (just as my college internship at the Chinese American Museum planted the seed for my book on Anna May Wong). Will has now been volunteering with CHSSC for more than 20 years, where he co-directs the Five Chinatowns project, documenting the history of the various Chinatowns that existed in Los Angeles between 1875 and 1965. He currently works at CSU Sacramento where he is an Assistant Professor of Asian American Studies in the Ethnic Studies Department.

In addition to all that, Will is the author of a new book called Performing Chinatown: Hollywood, Tourism, and the Making of a Chinese American Community, just out from Stanford University Press. His research on the Chinese American extras who helped make The Good Earth was incredibly helpful to me when I was writing about that moment in AMW’s career. And because the themes of our books dovetail so nicely, we’ve had the pleasure of doing several virtual and in-person events together. Now that the hullabaloo from AAPI Heritage Month 2024 has settled, we finally had a chance to catch up and talk about his work at length.

Tell us a little about your background and how you came to research and write about the Chinatown-Hollywood connection?

First, thanks so much, Katie, for giving me this opportunity to share a little about myself and my work with your readers! I am a fourth-generation Chinese American on my father’s side, and given this have always known that the history of Chinese America was much more complex than the very limited stories of gold miners and railroad workers that you learn about in school growing up. Yet, it wasn’t until after I began volunteering with the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California (CHSSC) that I really began to delve into the historical connection between Chinese Americans and Hollywood performance.

In 2004, I had completed my MA in Asian American Studies from UCLA and was beginning my work as a public high school teacher in Southern California. Around this time I began volunteering with the CHSSC as a community historian. One of the projects I ran was called the Chinatown Remembered Project, where I trained high school and college-age youth, to interview community elders about their experiences growing up in Los Angeles in the 1930s and 1940s. It was from this project that I really began to realize the complexity and importance that Hollywood played in the lives of everyday Chinese Americans in L.A. Nearly every Chinese American who lived in Los Angeles during this period either worked in Hollywood as a background extra or else knew someone who did. Despite its importance to the local community, almost no one outside of the community understood the extent of this history. I even realized that some of my own Chinese American relatives from this period had worked as extras. Something I had never heard about despite knowing them quite well.

When I decided to return to school and get my Ph.D. I knew this had to be the topic of my dissertation.

That’s so fascinating. The railroad, laundries, and restaurants loom large in Chinese American history since so many immigrants found work in those industries. But as you rightly point out, by the 1930s many in the community were also picking up background work in Hollywood films. I’ve met a number of people now, like Aimee Liu and Bo-Gay Tong Salvador, whose relatives had small speaking roles or worked as extras. I even have a great uncle who was an extra in M*A*S*H* apparently, which I’m still trying to learn more about since he wasn’t a credited actor and doesn’t turn up in IMDb.com.

Now, your book sets out to retell “the long-overlooked history of the ways that Los Angeles Chinatown shaped Hollywood and how Hollywood, in turn, shaped perceptions of Asian American identity.” Could you give readers one example of the representations of Chinatown that Hollywood projected and a strategy or aesthetic that Chinatown merchants adopted to challenge Hollywood stereotypes?

One of the most interesting aspects of this research has been seeing the myriad ways that the various members of the Chinese American community found agency during a moment when American racism marginalized members of the community socially, politically, and culturally in so many aspects of their everyday lives. Since before the arrival of the film industry in Southern California, the medium shaped popular opinions of Chinese Americans and Chinatowns. Most of their early film representations sought to portray Chinatowns as dens of inequity, where Chinese men smoked opium and kidnapped and abused white women. At the center of these stereotypes were representations of “underground Chinatown,” an imagined network of underground passages lurking below the streets of the Chinese American neighborhood. While some buildings in Chinatown certainly had basements, this underground Chinatown never existed to the extent that Hollywood or the popular press portrayed. Rather, I argue, underground Chinatown was more of an extension of the fears of the white imagination—primarily the fear held by many white leaders that Chinese Americans operated outside of the visual control of white society.

Chinese American merchants in Los Angeles and elsewhere pushed back against these representations of an underground Chinatown with their own representations of China and Chinese people. I dub the assemblage of techniques developed by Chinese American merchants to push back against long standing stereotypes of Chinatown while simultaneously seeking to profit from the mainstream white fascination with the imagined Orient—Chinatown Pastiche. Chinatown pastiche included everything from the pagoda-style architecture of Chinatown to the fortune cookies to the Orientalist font used in many Chinese menus of the period. Rather than viewing all these various things as inauthentic rip-offs of actual pieces of Chinese culture, we should regard them as what they were, a concerted effort by members of the Chinese American merchant class to profit off of white fascination with China in ways that empowered Chinese American merchants while pushing back against stereotypes that portrayed Chinese Americans as a “Yellow Peril” to white society.

I love that Sid Grauman, Hollywood’s ultimate showman, turns up in your book. He was the man behind The Egyptian Theatre, where The Thief of Bagdad premiered in 1924 (AMW’s breakout film), and the famed Chinese Theatre. Anna May Wong was invited to drill the first rivet into one of the steel beams used to build the Chinese Theatre and she also attended the groundbreaking ceremony in 1926 along with Charlie Chaplin and Norma Talmadge.

I learned from your book that this wasn’t the first time Grauman used a Chinese backdrop for one of his entertainment ventures. Tell us about his “Underground Chinatown” walkthrough exhibit in San Francisco and how it contrasted to Chinatown Pastiche.

Wow. Interesting. I wasn’t aware that Anna May Wong played that role in the groundbreaking ceremony of the Chinese Theatre. Sid Grauman was indeed quite the showman. Grauman began his career in San Francisco as a vaudeville theater owner and operator in the period before the 1906 earthquake and fire. In San Francisco, Sid and his father D. J. Grauman opened the Unique Theater, one of the nation’s first ten-cent vaudeville houses. Directly after the earthquake, Sid, the consummate showman, reportedly opened a tent theater under a banner that read, “Nothing to Fall on You Except the Canvas!”

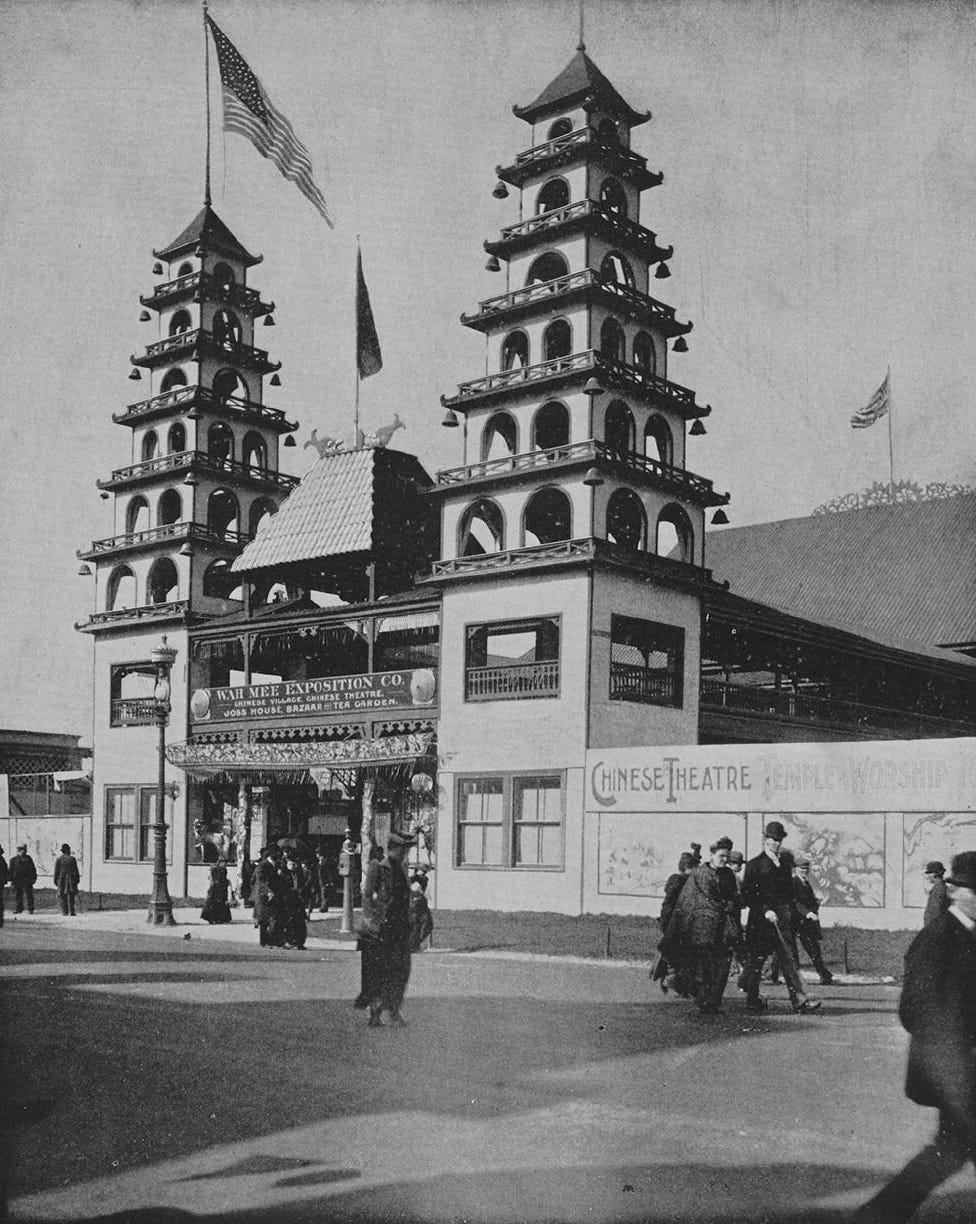

By 1915, Sid Grauman was thirty-six years old and owned multiple theaters in the city. With the city hosting the Panama Pacific Exposition that year, Grauman was not about to pass up the largest potential audience of his life. He decided to produce an exhibit in the Zone, the exposition’s midway. He subleased a space in one of the Zone’s existing attractions, “The Chinese Village and Pagoda Company.” Alongside the attraction’s eight-story pagoda, candy shop, theater, night club, and fruit stand, Grauman invested $12,000 to create his “Underground Chinatown.” Visitors to his exhibit witnessed a series of scenes featuring both wax figures and actors.

His exhibit peddled the worst of anti-Asian stereotypes, depicting Chinese immigrant men as violent drug users who lusted after white women. There was reportedly a scene where Chinese men plotted to kidnap a white woman.

Chinese American merchants in the city were outraged by the depictions of Chinatown. They protested and wrote letters to the president of the exposition. Bowing under pressure, Grauman closed the exhibit briefly, before reopening it under the name “Underground Slumming.”

Grauman wasn’t alone in perpetuating these stereotypes of Chinatown as a “Yellow Peril” to white American society. This was the period of the Chinese Exclusion Act—which barred all Chinese laborers from immigrating into the country. Popular representations of Chinese as violent drug users who threatened the middle class white family played an important role in maintaining support for these types of anti-Chinese laws. Grauman’s representations of underground Chinatown occurred at the very moment that Chinese Americans in San Francisco were developing their Chinatown Pastiche aesthetic to lure tourists to the rebuilt Chinatown in the city’s center.

I stumbled upon your dissertation (which was eventually adapted into your book) while I was researching the making of The Good Earth, the film that Anna May Wong famously did not play a role in. You make use of a number of oral histories from Chinese Americans who worked as extras in the film, which were especially fascinating to me. I cite several of them in my book. Out of all the films made about China during this period that called for Chinese American extras, why did you choose to write specifically about The Good Earth? What made that film such an important cultural moment for Chinese Americans?

Perhaps more than any text produced in the 1930s, The Good Earth shaped the way white Americans understood China and Chinese people. The film was based on Pearl S. Buck’s novel, which was released in 1931. The novel was the bestselling book in the United States in that year and it went on to receive international recognition, including winning the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Because of the book’s influence, MGM’s cinematic adaptation took on political importance on both sides of the Pacific.

As you note, Anna May Wong was passed over for a starring role in the film and nearly every central role in the film went to a white actor in yellowface makeup. Because of these racist hiring practices, most Asian American Studies scholars have dismissed the film as irrelevant. But there is another way to understand the film, which is through the eyes of the film’s extras and bit players. The film reportedly hired over 1,000 extras during a period in which there were only around 3,000 Chinese Americans in Los Angeles, which would be one in every three Chinese Americans living in the city. Even if the reported number is inflated, the film hired a significant portion of the ethnic enclave.

We have to remember that this hiring occurred in the middle of the 1930s, which was as we all know the height of the Great Depression. Racist hiring practices marginalized most Chinese Americans into the segregated labor market within Chinatown and so supplemental extra work on films like The Good Earth played an incredibly important economic role in the lives of many Chinese Americans in the city.

Another project that you’ve also been working on is The Five Chinatowns: A Community History, a collection of essays and stories about the five different incarnations of L.A.’s Chinatown, many of which no longer exist. And to which you kindly invited me to contribute an essay on AMW. What was the impetus behind that project?

This is a volume I am editing with Isa Quintana from UC Irvine and Kelly Fong from UCLA. The book is meant to serve a very different purpose than PerformIng Chinatown. Our Five Chinatown book invites community scholars, writers like yourself, journalists, and academics to retell the history of the Five Chinatowns that existed in Los Angeles before 1965 in a way that is accessible to a broad community audience. Alongside the narrative and analytical history pieces, the book will include dozens of longer excerpts of oral histories interviews with community members who lived in Los Angeles’s various Chinatowns during this period. It will also include scores of archival and family photos. As such, Five Chinatowns is very much a community history, produced by a large cross section of the community for a broad public audience.

Chinatown is a real place, but also a place of nostalgia and belonging that often lives in the hearts and minds of Chinese Americans everywhere. It’s a place many of us return to on a regular basis, whether on shopping trips or for meals with friends and family. What keeps you coming back to it in your scholarship?

Really, I keep returning to Chinatown—and L.A. Chinatown in particular—because of the friendships and community that I have developed over the years as a volunteer with the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California. As a fourth-generation, mixed race Chinese American, I never felt at home or even welcomed in most Chinese American organizations in college or in the community. Many Chinese American organizations cater toward Chinese immigrants. But when I joined the CHSSC in 2004, it felt like home. The membership of our organization very much reminds me of my own Chinese American family. Most of the members of the CHSSC are third- or fourth-generation Chinese Americans. And like me, they all share a passion for documenting and sharing Chinese American history with others.

Will’s book, Performing Chinatown: Hollywood, Tourism, and the Making of a Chinese American Community, was published last month by Stanford University Press and is available for purchase here. Use discount code GOW20 to receive 20% off when purchasing directly from the publisher. The book is also available at Bookshop.org and most other online book retailers.

As a bonus, you can check out a recording of me, Will, and Karen Fang (Tyrus Wong’s biographer) in conversation with Jeff Yang (author of The Golden Screen), discussing Chinese Americans in classic Hollywood on YouTube.

once I started reading, I couldn't stop!!

This is good stuff.