When reporters asked Anna May Wong about her family and whether she had any brothers and sisters, she answered cheerfully that there were, in fact, seven Wong children. “We’re not a family—we’re a dynasty,” she’d add with a twinkle in her eye.

As modern and outré as AMW was for a Chinese American woman in the 1920s, eschewing marriage for a career in the movies against the wishes of her parents, there were some traditional values that she held quite dear. Family was deeply important to her, and her loyalty and dedication to her brothers and sisters was unwavering.

Perhaps it had something to do with her parents. Wong Sam Sing and Lee Gon Toy were both born in California in the late 1800s, the children of immigrants who had been lured from Southern China to seek their fortunes on Gold Mountain. Both were only children. Wong Sam Sing lost his mother at the age of five and was raised by relatives for a time while his father continued running his general store business in the mining town of Michigan Bluff. Lee Gon Toy’s father ran a cigar factory in San Francisco. At the tender age of 15 she married Wong; the couple was match-made through a marriage broker, as was the custom of the times. Wong was 41. Lee lost touch with her parents when she moved down to Los Angeles with her new husband. After some years her parents returned to China and she never saw them again.

It makes sense in a way that together, Wong Sam Sing and Lee Gon Toy would produce a large family, a kind of substitute for the one they lacked growing up in the wilds of the Western frontier. Lulu was the first of the clan and born in 1902.

“Her arrival was not the signal for any rejoicing in the family,” AMW recalled in her memoirs for Pictures magazine in 1926. “In fact, when father found out that his first child was a girl he was so disgusted that he didn’t come home for days.”

Little Anna came next in 1905. While Wong Sam Sing bemoaned the delivery of yet another daughter, two girls in a row was a blessing in disguise. Lulu and Anna protected and helped one another. Together they survived the racist taunts of the kids at the California Street School, endured the tedium of after-school Chinese classes, and made trips up and down the hills of downtown Los Angeles delivering laundry packets to their dad’s customers.

When AMW embarked on a months-long tour across the country with the Cosmics, a band of young, unknown actors, in 1925, Lulu went along with her. Lulu was there, too, when AMW sailed to Europe for the first time. For a few months in 1928, Lulu got to live vicariously through AMW’s celebrity. Watching strangers mob her younger sister in the streets of Berlin, Paris, and London must have been something else.

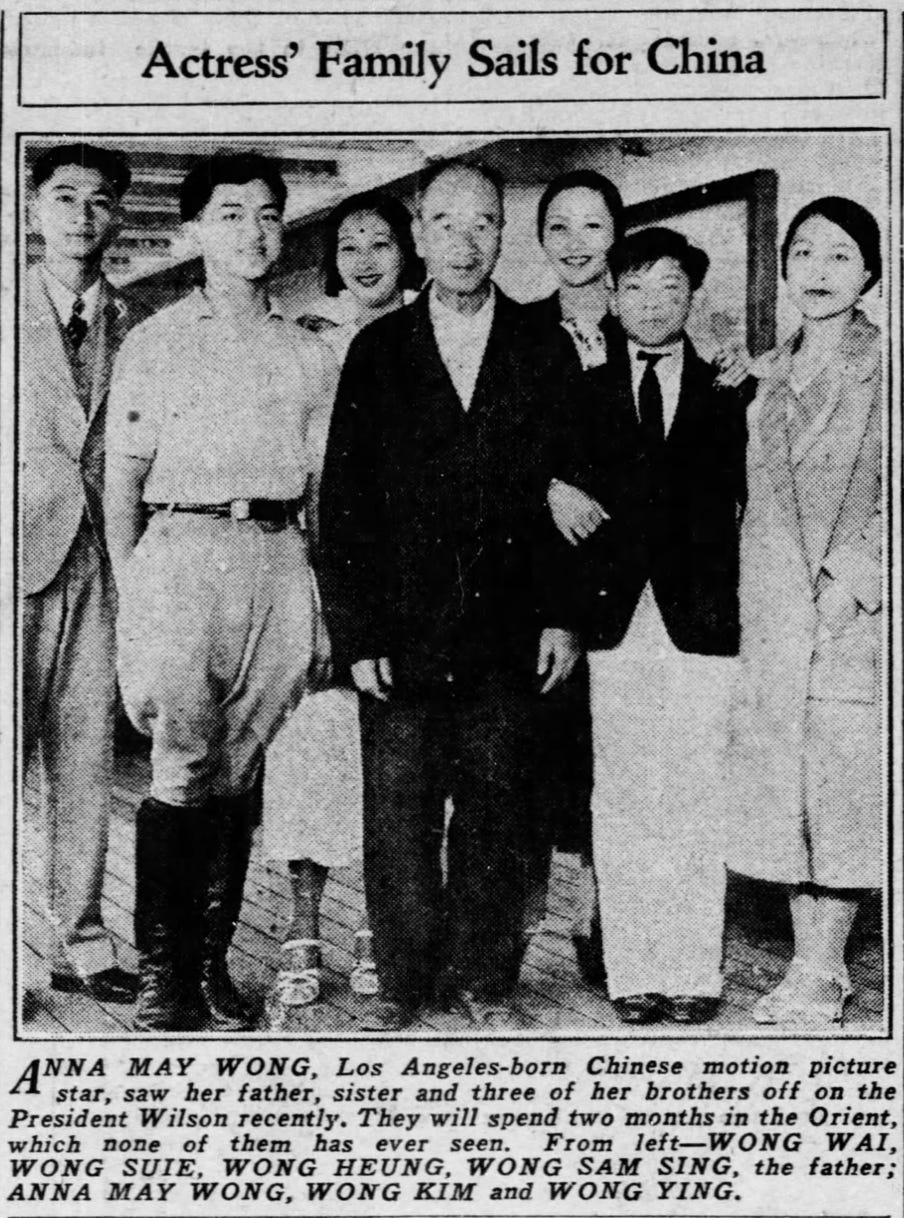

Wong Sam Sing, however, needn’t have worried that he wouldn’t have any sons to carry on his name (actually, he already had a son, Huang Dounan, back in China by his first wife—but that’s a story for another newsletter). James was born next, followed by Mary, Frank, and Roger. A girl named Marietta was born in 1919, but unfortunately did not survive past infancy. The dynasty ends with Richard, the baby of the family, born in 1922—the same year a 17-year-old AMW was busy playing her first leading part in The Toll of the Sea.

“He got his boys all right,” AMW remarked of her father. “The last one is only four months old. I hope one day he’ll be satisfied.”

The newly minted movie star, though, did not forget her younger siblings, who were still in school and working at the laundry. Instead, she showered them with gifts and helped them in whatever ways she could. On her first trip to Canada to film The Alaskan in 1924, she returned to L.A. with three suits made of “the finest English material” for her brothers. She paid for her siblings’ educations and got them parts in her movies. She even appeared in court on behalf of her brother James when he was given a bum ticket for possession of fireworks on the 4th of July.

By the time AMW was 20, she was making enough money as an actress to get her own place, but she flip-flopped, moving in and out of the family laundry to Hollywood and back several times. Living alone, it turned out, was excruciatingly lonely compared to the close quarters and family meals she was used to sharing back on Figueroa Street.

“People criticize me because I live with my parents in their laundry, instead of ‘elevating myself,’ whatever the dickens that might be. But I can’t leave my people, can I?” Anna May reasoned.

Eventually she did move out of the old Sam Kee Laundry, spending the better part of the 1930s abroad in Europe or living in apartments at the Park Wilshire in Los Angeles. But the pull and tug of family, the comfort of being surrounded by the people who know and love you best, never left her.

Some time in the 1940s, AMW used her savings to buy a Spanish-style house on San Vicente Blvd. in Santa Monica. She had a round Chinese gate added to the property and christened it Moongate. Her youngest brother, Richard, moved in while he was finishing up his college studies. Though they were 17 years apart, the two grew close. They were both garrulous, fun-loving people with the same streak of iron-willed stubbornness that seemed to run through certain members of the Wong family.

In the same way that AMW had supported her younger siblings through their schooling and early careers out of a sense of duty and familial love, Richard was there for his big sister when she needed him most. These were the years when AMW’s health was in decline. She had been diagnosed with cirrhosis (whether this was caused by alcoholism is still disputed) and her looks were also fading, a side effect of the disease that aged her skin and caused her to look much older than she was. Winning roles in major Hollywood productions was increasingly difficult since she no longer looked the part of the exotic Asian temptress. Her time in the limelight, like many of classic Hollywood’s aging actresses, was coming to a close.

On the night of February 3, 1961, Anna May Wong died in her sleep of a heart attack, likely complications related to cirrhosis. She never married or had children of her own, but she did not die alone. Richard was there and the first to know that she had finally left this world.

Life, of course, goes on, as it must. Within a few years of his sister’s passing, Richard got married. Soon he and his wife were expecting their first child together. It was a girl, only this time, rather than being disappointed, the father was overjoyed. He knew exactly what a precious gift a baby girl can be. He would name her Anna May—so that the memory of his sister would live on, so that the Wong dynasty would continue.

My mother was teaching school in Nome, Alaska in 1933 when she became friends with Lulu Wong Ying, who was acting in the MGM film “Eskimo” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eskimo_(1933_film)), which was being filmed in the Nome area. I have several photos taken at the time that include Lulu. Also, letters Mom wrote to her mother that include references to Lulu. Sample:

“Feb. 26, 1933

“This morning we went out on the ice to watch them taking pictures, but didn't see much. They've finally given up getting any snow, so they're starting home this week, i.e. the first load of them will start to Fairbanks Tuesday. Some of the party are going north again to get some pictures of polar bears, & the rest will go back to Hollywood where they will have to manufacture the snow scenes. Lulu, the Chinese girl will be among the first to leave, & I've told her to look you folks up if it is convenient to do so when they go thru Ketchikan. Her full name is Lulu Wong Ying & she's a sister of Anna Mae Wong. You'll probably hear from her about the 15th or 16th of March, as they are supposed to leave Seward on the 12th. She's a very friendly girl & is one of the party who seems to be sorry to have to leave. I think the fact of the matter is, that she's welcomed here as a movie star, & is much more important than she is in Hollywood. It was her parka that I wore in the snapshot I sent you.”

charlieburrow@gmail.com

Good detective work!