Despite the recent assault on diversity, equity, and inclusion—and MAGA’s co-optation of DEI into a racist dog whistle—the last two decades have witnessed countless groundbreaking milestones for people of color in this country. We have always been a part of the fabric of this nation, but history books, pop culture, C-suite boardrooms, and other public arenas like the halls of government have often told a different story. One that sanitizes our collective memory of nonwhite contributions. Celebrating the historic firsts for people of color and other marginalized folks has become a way to counteract this trend. Here are just a few significant firsts that come to mind from the last two decades:

Barack Obama, first Black president

Michelle Yeoh, first Asian woman to win an Academy Award for Best Actress

Sonia Sotomayor, first Latina to serve as a Supreme Court Justice

Colman Domingo, first openly queer Afro-Latino to receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor

Kamala Harris, first Black and Asian woman elected as vice president

Misty Copeland, first Black female principal dancer at the American Ballet Theatre

BTS, first Korean group to be nominated for a major Grammy category

Naomi Osaka, first Japanese player to win a Grand Slam singles title in the U.S. Open

In my day job as an editor, I’ve also worked with the first Latina in NPR's newsroom (and many subsequent newsrooms) and the first Asian Canadian woman in the hip hop industry who brought Wu-Tang Clan to China. The list of firsts is infinite. But as more and more are achieved each year, the categories in which historic firsts have yet to be accomplished become a little narrower, a little more obscure.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying we shouldn’t celebrate these wins. We absolutely should. Most of these accomplishments have only become possible in the last several decades through the sustained efforts of activists and artists who continued pushing for equality in the face of a real, entrenched resistance.

But I’ve noticed that in our rush to claim someone as “the first” to achieve a historic designation, we sometimes erase the important work of earlier figures whom public memory has long since forgotten (which, ironically, is partly due to the fact that earlier generations did not celebrate these hard-won firsts).

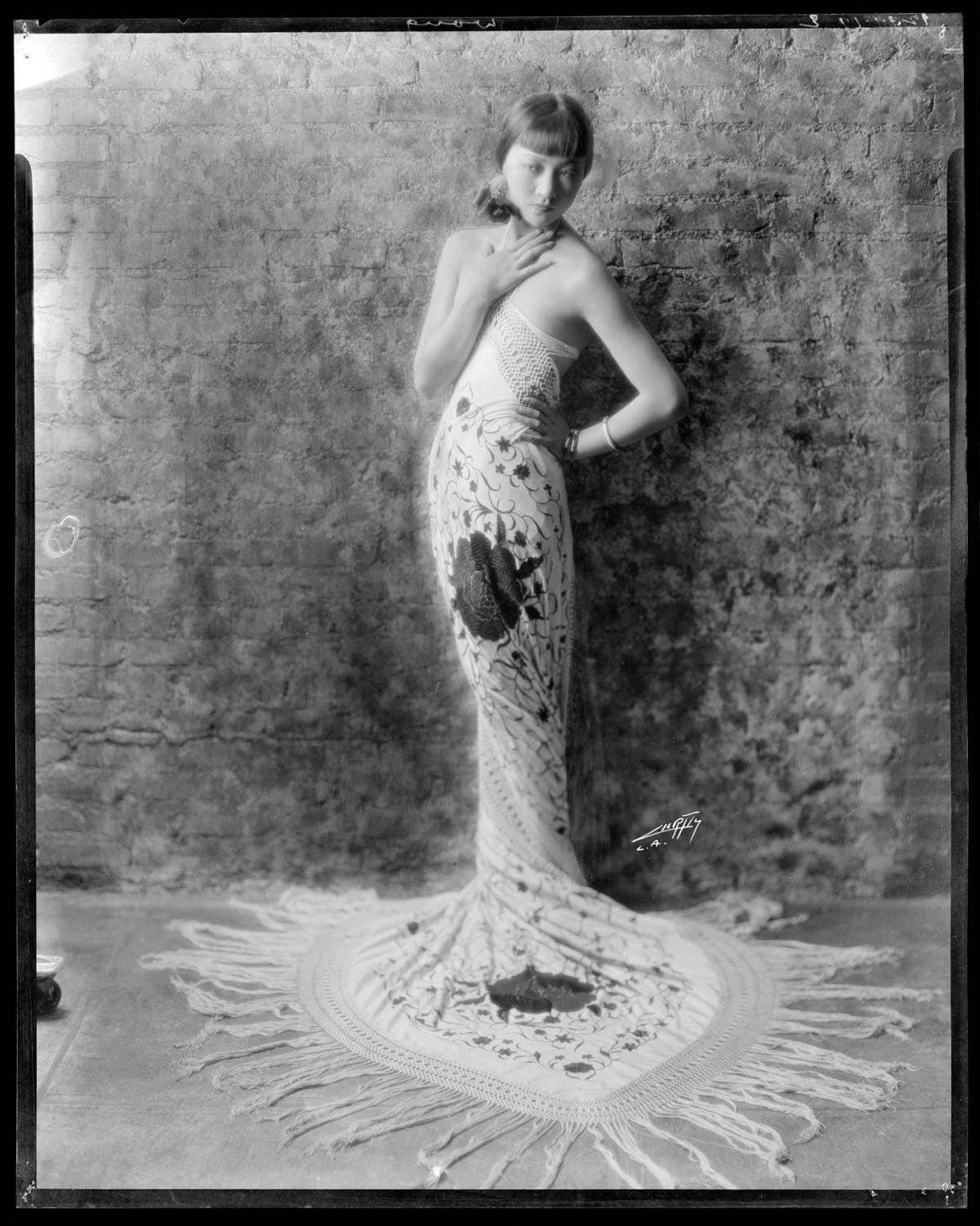

I have long considered Anna May Wong to be Hollywood’s first Asian American movie star. To be precise, she was the first major Hollywood actress who was both American-born and of Asian ancestry. But that hasn’t stopped Asian American actors in subsequent eras from claiming the status for themselves.

In a 1969 letter that outlined his chief goals, Bruce Lee wrote: “I, Bruce Lee, will be the first highest paid Oriental super star in the United States.” Last time I checked, Anna May Wong beat him to the punch by about 50 years! But I’ll give Bruce the point about being the “highest paid.” AMW certainly never received the kind of pay her white colleagues did for playing Asian parts in yellowface, even when she got top billing. (When Paramount produced Daughter of the Dragon (1931) as a starring vehicle for Anna May, her salary was $6,000, while her co-stars Sessue Hayakawa and Warner Oland received $10,000 and $12,500 respectively.)

Nancy Kwan, the 1960s It girl who starred in The World of Suzie Wong and Flower Drum Song, recently published a memoir aptly titled The World of Nancy Kwan. An early version of the subtitle, however, called it “A Memoir by Hollywood’s First Asian Leading Lady and Global Star.” In reality, there were a number of Asian leading ladies in Hollywood before Kwan, including AMW. The subtitle was corrected for publication to “A Memoir by Hollywood’s Asian Superstar.” And though I doubt this flub originated with Kwan herself—it was more likely a mistake made by her ghostwriter or publisher, overeager to headline some notable status that could fit in a sound bite—it’s another example of the irresistible urge to name someone “first” whether or not we know who became before them.

In February, when writer and actress Mindy Kaling received her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, she noted in an Instagram post: “I was told after receiving my star that I was the first South Asian woman to have a star on the Walk of Fame. I’m humbled by that. I am so proud to be South Asian and I want to make my community proud of everything I do but more importantly I want to help usher in the next generation of South Asian stars - who are already making a huge impact across the world.” I’m a fan of Kaling’s work and applaud her induction to the Walk of Fame. But there’s one thing we have to clear up: As friend and writer Mayukh Sen has pointed out, Merle Oberon was the first South Asian to earn a star in 1960, when the Walk of Fame was originally created. Was it the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce that misinformed Kaling? Could it be that they didn’t know the history of their own institution?

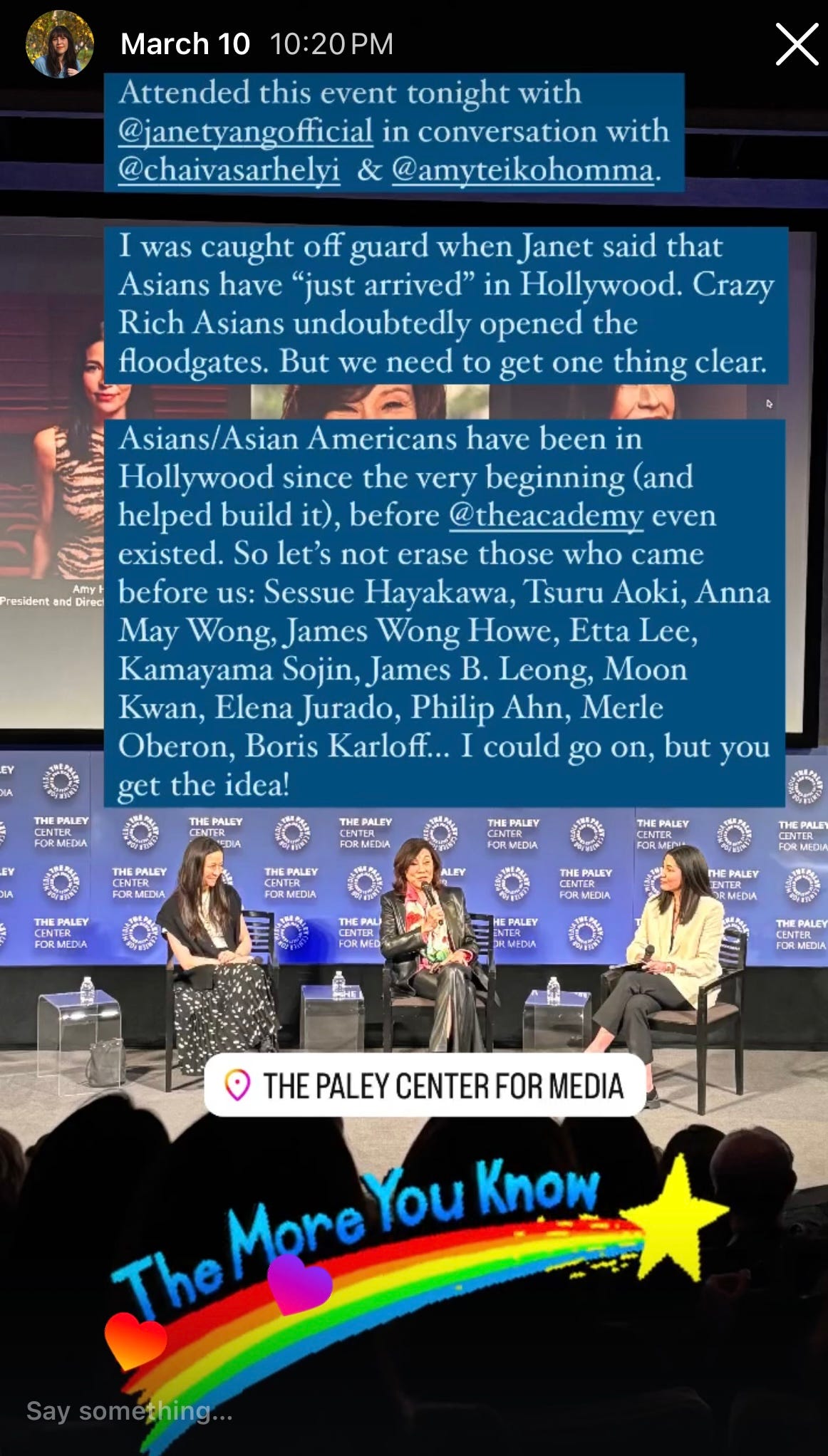

Earlier this spring, I attended an event in New York City hosted by The Serica Initiative with guest speakers Janet Yang, president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Amy Homma, Academy Museum director and president, and Chai Vasarhelyi, Oscar-winning filmmaker. The speakers were all Asian American and the audience was also heavily Asian, so the conversation naturally steered towards Asian Americans in Hollywood. I was caught off guard, though, when Yang casually explained away the lack of progress in Asian representation until Crazy Rich Asians came out in 2018. Asians, she said, have “just arrived” in Hollywood. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Of all people, I would expect Janet Yang, president of the Academy, to know her Hollywood history. Asians have been working in the industry since the very beginning; in fact, they were pioneers in the film business. Ever heard of James Wong Howe or Sessue Hayakawa? When my book on Anna May Wong came out last year, I personally mailed Yang a copy. Perhaps she never got around to reading it.

As much as I rail against erasures like these, which expose our profound ignorance of history, I myself am guilty of doing the same.

While I was researching Anna May Wong’s life and career, one question kept recurring: Was AMW the first woman of color to become a star in Hollywood? And more specifically, was she the first woman of color to play a leading role in a Hollywood production?

Immersed in the details of her meteoric rise, I soon realized her early success in the industry—first as the lead in The Toll of the Sea (1922) and then in a supporting role in The Thief of Bagdad (1924)—predated many of the well-known actresses of color we still hear about today. I began keeping a list:

Dolores Del Rio - appeared in her first film in 1925, first starring role in Pals First (1926)

Lupe Vélez - appeared in her first film and starring role in The Gaucho (1927) opposite Douglas Fairbanks

Josephine Baker - appeared in her first film in 1927 and first starring role in the French film Siren of the Tropics (1927)

Nina Mae McKinney - appeared in her first film and major role in Hallelujah! (1929)

Fredi Washington - appeared in her first film in 1929, first major film role in The Emperor Jones (1933), first major role in a Hollywood production in Imitation of Life (1934)

Merle Oberon - appeared in her first film in 1928, first major role in the British film The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933), first starring role in a Hollywood production in The Dark Angel (1935)

Hattie McDaniel - appeared in her first film in 1932, first major role in Judge Priest (1932)

Ethel Waters - appeared in her first film in 1929, first major role in Rufus Jones for President (1933)

Just looking at the dates collected here, one could easily assume, then, that Anna May Wong was first in this regard. But that’s only if you take this list at face value, which I have to admit is rife with caveats. First off, it’s not exhaustive. There are other women of color who worked in Hollywood during the 1910s and 20s like Etta Lee and Madame Sul-Te-Wan (also known as Nellie Wan) and Elena Jurado, but they rarely, if ever, played leading roles and one could argue they never rose to star stature.

Then there’s the question of whether the films were made in Hollywood or not. Actors of color often had to make films outside the Hollywood system in order to work at all. So it’s no surprise that Josephine Baker, Fredi Washington, and Merle Oberon first played major roles in films made elsewhere.

And with any list, you have to ask yourself, what’s being left off? What is being erased by omission? By designating AMW “first woman of color to become a star in Hollywood,” I knew I’d be excluding some of the pioneering actresses who got their start in race films. These were films shot with all Black casts, made specifically for Black audiences beginning as early as 1915. Oscar Micheaux is a legendary example. He was a Black filmmaker who founded his own film corporation and in 1919 released his first film, The Homesteader, starring Evelyn Preer.

A parallel example from the Chinese American community is Marion E. Wong who founded the Mandarin Film Company in 1916. That same year she wrote, directed, and acted in the film The Curse of Quon Gwon: When the Far East Mingles with West. Another actress who emerged from such films was Lady Tsen Mei, or Josephine Augusta Moy, a mixed race actress who played the leading role in the 1921 film Lotus Blossom, produced by James B. Leong’s company Wah Ming Motion Picture Co.

Finally, you have to address the fact that the absence of Black women in early Hollywood is not for lack of talent or ambition but due to the reality of racial codes in the United States. The country was largely segregated and Hollywood studios wanted to make films they could distribute all over the country. Southern states like Alabama and Mississippi refused to show films that featured Black actors in major roles. As a result, Black people were relegated to subservient bit parts or parodied by white actors in blackface. Thus, Black women were shut out of the industry until the late 1920s and early 30s.

Knowing all this, it isn’t hard to see how an opportunity for someone like Anna May Wong came along. Asian Americans have long been used to triangulate race relations between Black and white Americans. The model minority stereotype from the 1950s is a textbook manifestation of this. Allowing Asian Americans and other minorities to succeed in the face of Black oppression was and continues to be a way for those upholding the racial hierarchy to claim that the system is fair and merit-based even when it’s not.

Claiming Anna May Wong as the first woman of color to become a Hollywood star took me into troubled territory. And yet, for whatever reason, I felt compelled to claim another “first” for her, even though I knew I was going out on a limb. Nervously, I put the claim in print in the preface and epilogue of my book. I had originally wanted to qualify this designation by writing a companion essay, much like the one I’ve just laid out for you, that would explain how an Asian American could break through in Hollywood when Black women were excluded from the industry. I pitched the idea to a few outlets around the publication of Not Your China Doll. Nobody seemed to be interested. (Unfortunately, it’s still quite difficult to get the mainstream media interested in women of color, first of their class or otherwise.) In the end, it’s a good thing I didn’t write that essay—because I was completely, utterly wrong.

Two actresses predate Anna May Wong and all of the other women I’ve already mentioned. The first was sitting right under my nose the whole time: Tsuru Aoki, the Japanese American actress who made her film debut as the female lead in The Wrath of the Gods (1914) opposite Sessue Hayakawa. The two actors were married and often appeared in films together over the course of their careers. Industry lore has it that Tsuru was signed by Thomas Ince first; it was only through her lobbying that Ince was convinced to sign Sessue as well. Of course, I’d done the male chauvinist thing of thinking of Tsuru Aoki merely as Sessue Hayakawa’s wife! How embarrassing. How could I have overlooked her?

Similarly, I neglected to explore the history of Indigenous film stars. Another massive failure. It’s not hard to find Lilian St. Cyr, who was known by the stage name Princess Red Wing, provided you actually look for her. A member of the Winnebago Tribe and of Ho-Chunk ancestry, St. Cyr was the first Native American actress to appear in a silent film. Her first on-screen appearance was likely in The White Squaw in 1908. She and her husband also consulted on films made by D. W. Griffith about Native Americans. Then, in 1914, Cecil B. DeMille cast her in a major role for his film The Squaw Man. She was paid significantly less than her white co-star, who received $1,000 a week. Apparently, after noting the pay disparity, one reporter suggested it was an honor for her to work alongside such a highly paid actor. St. Cyr responded matter-of-factly: “What about him? He’s working with a one hundred percent American.”

CORRECTION: A reader pointed out in the comments that Lilian St. Cyr was not the first Indigenous woman to appear on-screen. I’m not surprised! They note that Esther Eneusteak, an Inuk woman, appeared in three short films made my Edison Studios about the Inuit people in 1901. Minnie Devereaux (sometimes also Minnie Provost), a citizen of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, also appeared in a number of early Hollywood silents beginning in 1913.

By all rights, Lilian St. Cyr would seem to be the first woman of color to play a major role in a Hollywood production. I’m ashamed it took me this long to learn about her. But if this essay has proven anything, it’s that the question of “Who was first?” is the wrong one to be asking.

Our obsession with firsts comes from a good place. It was born out of a desire to recover important overlooked figures, to make sure everyone gets their flowers. That’s a noble intention. But like most things, it has been corrupted by the click machine. I’m as guilty of this as anyone.

In April, I submitted a correction for the next printing of Not Your China Doll:

p. xii, 3rd paragraph, change “She was also, significantly, the first woman of color to become a movie star in the Hollywood system.” to “…one of the first women of color to become a movie star…"

It’s a simple fix for an unforced error. It also subtly shifts the emphasis from the singular to the collective and points the way to something I missed. The question we should be asking is: “Who came before?” Who paved the way so that she could soar, the predecessor who only dreamed of one day flying? All of us are following in the footsteps of others, even when we break new ground. Remembering that keeps us humble—and more importantly, it keeps the memory of those who came before us alive.

Updates in Brief

It’s the last week of AAPI Heritage Month and I thought I would share some of the AAPI-authored books currently on my shelf (see above). If you’re looking for your next read, check out one of these books! This month I also wrote about Tsuru Aoki’s husband (see what I did there?), Sessue Hayakawa, for History.com. Speaking of firsts, Sessue was one of Hollywood’s earliest heartthrobs who made way for later idols like Rudolph Valentino.

If you’re in the Houston area, I’ll be attending the 21st annual HAAPIFest, a film festival showcasing films made by Asian American and Pacific Islander creators. I’ll be speaking about Anna May Wong at the top of the program on Saturday, May 31. Learn more about the festival here.

On June 21, I’ll be speaking about AMW in a virtual event with the San Diego Chinese Historical Museum, which is free and open to the public. The next day I’ll be introducing a screening of The Toll of the Sea at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York along with Anna Wong. I hope to see some of you there!

I stand in awe of your attention to detail and research!

Great essay. The same thing is true in science. We like our history neat and tidy: Person X discovered thing Y. But reality almost always is messy and several others would have bits and pieces of Y if not the whole letter.