Black Hollywood’s Fete for United China Relief

that time Hattie McDaniel, Clarence Muse, Billie Holiday & the Nicholas Brothers hosted a fundraiser with Anna May Wong

Last summer while I was preparing for an event at the Los Angeles Breakfast Club (LACB)—a fun and kooky group that has been meeting weekly at the crack of dawn for nearly 100 years—I received a request from the group’s archivist. Did I know whether Anna May Wong had ever attended an event at the club?

This question sent me down a research rabbit hole, as most innocent questions about Anna May Wong do. I immediately ran a search on newspapers.com. One result in particular caught my attention: a United China Relief benefit hosted by the NAACP in May 1942.

I’d never come across this entry before in AMW’s frenzied schedule of United China Relief fundraisers in the late 1930s and early 1940s. As I write in my book, AMW threw herself into the war efforts in the years leading up to and during WWII, hosting countless Bowl of Rice fundraiser galas, signing autographs in exchange for donations, auctioning off her personal wardrobe, and making propaganda films from which she donated all the proceeds. She was even sworn in as an air raid warden in Santa Monica.

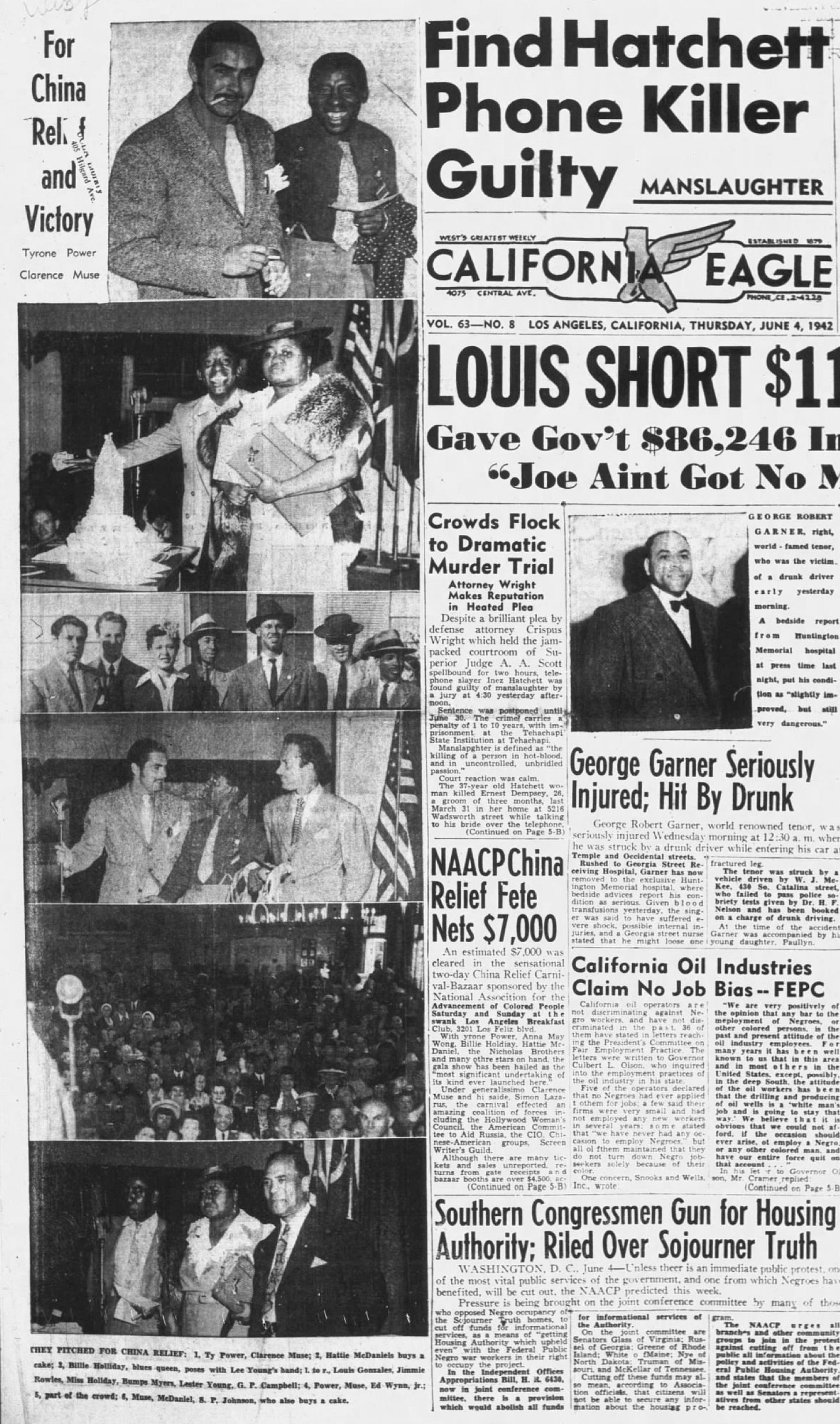

The exclusion of the NAACP benefit seems partly due to the fact that the two-day event was only mentioned in a cursory way in mainstream publications like the Los Angeles Times and other local papers. This clipping, however, was from the front page of the California Eagle, a historic African American newspaper first founded in Los Angeles as The Owl in 1879. It’s the only paper I’ve found that recapped the event in detail:

An estimated $7,000 was cleared in the sensational two-day China Relief Carnival-Bazaar sponsored by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Saturday and Sunday at the swank Los Angeles Breakfast Club, 3201 Los Feliz Blvd.

With Tyrone Power, Anna May Wong, Billie Holiday, Hattie McDaniel, the Nicholas Brothers and many other stars on hand, the gala show has been hailed as the “most significant undertaking of its kind ever launched here.”

I’d struck research gold. I had always sensed that AMW harbored a feeling of solidarity with Black artists. She was good friends with Paul Robeson and showed up, quite visibly, to support his opening night in Othello at London’s Savoy Theatre. Her decision to leave Hollywood in the late 1920s and try her luck in Europe can also be understood as an effort to follow in Robeson and Josephine Baker’s footsteps. Just one year before the NAACP fundraiser, she spoke at a special United China Relief performance at the LA Philharmonic of Cabin in the Sky, an all-Black Broadway musical featuring Ethel Waters that was later adapted into a groundbreaking Hollywood film.

Here, finally, was evidence that placed Anna May Wong in the same room with Hollywood’s Black luminaries, joining forces to support a political and humanitarian cause, mainly the welfare of Chinese citizens displaced and harmed by Japan’s conquest of Asia during WWII. The event highlights a sincere moment of Black-Asian solidarity. One promotional article in the California Eagle explained that, “Main theme of many of the leaders who are supporting the affair is the responsibility that The American Negro, as an oppressed people, owes to the oppressed people of the world.”

The man in charge of the festivities was Clarence Muse, an actor distinguished for being the first African American to play a leading role in a Hollywood film who was also a representative for the NAACP. Under his direction, 12 local organizations came together to host the fundraiser, including the Hollywood Woman’s Council, the American Committee to Aid Russia, the Screen Writers Guild, and various Chinese American groups, among others. The California Eagle noted that these groups “offered their services to work hand in hand with the NAACP in a true spirit of interracial unity.”

The first day of the two-day program consisted of an “all-Negro artist program” as well as the display of “art and other objects of workmanship” by Black Americans; the second day, called “International Day,” presented entertainment from artists of all nations. Several Hollywood stars—Hedy Lamarr, Joan Fontaine, Merle Oberon, Olivia de Havilland, Deanna Durbin, and Martha Raye—donated gowns from their wardrobes to be exhibited and auctioned off.

The names slated to perform were Black Hollywood’s biggest and brightest stars. (Yet somehow the mainstream newspapers didn’t think that was newsworthy enough to warrant a write-up.)

Hattie McDaniel, fresh off her Oscar win in 1940 for her role as Mammy in Gone with the Wind, was mobbed by fans as her “bodyguard struggled to get her through the crowd.” Despite her success, some in the Black community criticized McDaniel for playing maids and other demeaning on-screen roles. To which she responded, “I'd rather play a maid than be one.” McDaniel, much like AMW, had little control over the roles she played and often had to make the choice between taking a less than ideal role or not working in Hollywood at all. The two women are both buried in Angelus Rosedale Cemetery, one of the first cemeteries in Los Angeles to accept people of all colors and creeds. (People were segregated by race in death, too.)

Other stars included singer and actress Ethel Waters, famous for songs like “Stormy Weather”; actor and comedian Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, best known for his role as Rochester van Jones on the radio show The Jack Benny Program; the incomparable Billie Holiday, the jazz singer beloved for her renditions of “All of Me” and “The Very Thought of You”; and the dancing duo Nicholas Brothers, who some consider the greatest tap dancers of all time. Watching their stair dance in Stormy Weather (1943) takes my breath away every single time.

Under a column headlined “Personalities Seen While Strolling Through the Bazaar-Carnival,” California Eagle reporter Harry Levette opened his recap with: “Anna May Wong, still beautiful Chinese star, who sprung to fame in Doug Fairbanks sr.’s historic silent, ‘The Thief of Bagdad,’ now working hard on relief drives for her native land.” The event was dubbed a huge success, bringing in $7,000 in receipts and an estimated 10,000 visitors.

All of these details were tantalizing. I could almost feel the electricity in the air that day with so many brilliant performers in the room. But still, I wanted more. I hadn’t come across any photos of AMW. Can you imagine her standing next to Hattie McDaniel or Billie Holiday or the Nicholas Brothers? If only someone had captured the moment on film, it would have been a piece of history immortalized.

I shared my findings with the LABC archivist, hoping she might be able to locate a photo of AMW at the event since none were included in the California Eagle. It turned out the NAACP had rented LABC’s space for the fundraiser, and because the event wasn’t hosted by LABC itself, it wasn’t documented in their archive.

I wasn’t ready to give up, so I followed a few other loose threads. I reached out to the librarians at the Southern California Library, which houses a collection of photographs from the California Eagle. They told me neither Anna May Wong nor this specific event came up in any of the metadata tags for the collection, but I decided I might as well take a look anyway the next time I was in town. That’s the thing about archival research, things sometimes fall through the cracks, wind up in unmarked files, or get left out of finding aids. In this case, things were as they seemed. No pictures of AMW miraculously turned up. Though I did come across some other nifty images: one of Paul Robeson with Charlotta Bass, publisher of the California Eagle, and the other of Hattie McDaniel being interviewed at the 1947 Academy Awards.

I also reached out to the NAACP’s Los Angeles branch office to see if they maintain any archival files. Of course, it was a long shot, and I wasn’t surprised when I didn’t hear back. So that’s where things currently stand. This might be a stumper for all you online sleuths: to locate a photo of Anna May Wong at the NAACP’s United China Relief fundraiser held at the Los Angeles Breakfast Club on May 30, 1942. Unless you can make her face out in this crowd!

Even without a photo placing AMW amidst the action, this idea of “interracial unity” and the ethos of mutual aid, of Black Power supporting Yellow Peril, if you will, stuck with me. The most remarkable part of the California Eagle’s coverage was an editorial published several days later. There is no byline attached to it, but it appears in the newspaper’s editorials section, which makes me think Charlotta Bass herself might have penned it. She was, after all, one of the benefit organizers and attended the festivities.

The editorial begins by stating, “the carnival was altogether an eloquent demonstration of the democratic theory put to practice. Some of the racial elements on hand were Chinese, Negro, Jewish, and a variety of nationalities which defies itemizing.” Remember, this was 1942, before the civil rights movement, when segregation ruled most interracial interactions. The fact of different minority groups working together to support a foreign nation, no less, was quietly revolutionary.

Then the editorial moves on to describing the soul-piercing performance given by Billie Holiday:

Sign of the times was Billie Holiday’s triumphant rendition of “Strange Fruit,” the somber, blues chronicle of a lynching. Its heartbreaking truth, its simple, poetic statement and the singer’s inspired interpretation created a moment Sunday that did more for the welding of the unity of our American people than a hundred speeches or a thousand editorials like this. The song’s last line hung like a pall over its audience, “Southern trees bear a strange and bitter fruit.” When the spell was finally broken, there tore loose a burst of applause that echoed for long minutes. Few in that auditorium will ever again regard the anti-lynching bill as “nuisance legislation.”

This moving passage sets up the next, which raises an urgent question:

Why should Negro people, in the midst of segregated military service, discriminatory war industries and a profound ostracism from the general flow of American life, worry over the plight of Chinese soldiers thousands of miles away, in another world? The answer is fraught with significance.

The rest of the essay is devoted to answering this question. I can’t help but reproduce it here in full because it is sadly relevant to what’s going on in America today, 80 years later, with the return of full-scale fascism and sieg heil salutes openly demonstrated by a small group of white men now running the US government.

Negro people, along with millions of liberal whites, Jews, Chinese, loyal Japanese-Americans, and Filipinos, are beginning to think in the terms of global war . . . not only in the military sense, but politically, too.

How is this? What change from a former outlook has occurred?

Well, world events in the past have been important to American Negroes only insofar as they have affected the immediate status of American Negroes. Throughout the entire twenty-year decline of democratic government in Europe, capital continent of the whole submerged colonial world, colored people here have never raised their voice in any vocal apprehension. When the Hitler brutalities were first launched against Jewish Germany, the Negro newspapers were frankly critical of the white press’ concern over these events. How come, our journals inquired, persecution of Jews three thousand miles across the briny deep could bring forth crocodile tears in the dailies when disfranchisement, exploitation, terror and lynching directed against Southern Negroes drew only a thunderous silence. Which was, and is, a good question.

Yet it demonstrated a viewpoint thoroughly isolated from the broad sweep of human events. We saw little kinship in the Chinese’ ten-year old battle against Fascism and our own struggle against its American counterpart. We saw little kinship in the rise to power of the world’s worst race-baiter, busily getting himself heiled all over distant Germany, and the operation of our own appeasers, our jim crow laws, our anti-vote statutes. Hitler we dragged into our arguments when we wanted to call somebody a bad name, but there was no real foresight as to the world-wide outburst of reaction the Nazi creed would call forth.

. . . What must happen to the thinking of millions of American Negroes,—and is happening, if the Relief Bazaar is any indication,—is a thorough-going recast of our approach to the problems we encounter as a minority group. We must view these problems in their proper connection with the history of our times. Concern with international affairs, with the machinations of high finance, with “global” outlooks, must no longer appear to us as off the subject, for the simple reason that nothing could be further from the truth. We have been and are directly influenced by what happens today in Berlin, Germany; Moscow, Russia; New Delhi, India. Our destiny is one and the same with that of all the Axis-hating people of the world. American Fascism today is weaker than it has been in a long time; it is in the curious position of fighting a war against itself. This is no war to settle competition in raw materials and markets. Strive as they might, the gods of the mill and the factory cannot make it one.

Why? Because the people are awakening. Because they are not so stupid that they will die this time to end a foreign Fascism and preserve one at home. THe conscience of the people is disturbed. Complacence is gone. An NAACP supported China Relief Bazaar two years ago would never have happened . . . certainly not with the spontaneous support of such widely divergent groups as made this week-end at the Los Angeles Breakfast Club an historic occasion.

And awaken they did. The post-war years brought enormous and necessary change to America. Historic court cases like Brown v. Board of Education helped bring an end to legal segregation, Jim Crow laws were dismantled, and Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. And yet, many of these gains in the arc of the moral universal have been chipped away at over the last ten years by Trump and his cronies. Which brings us to the current moment, where we stand at a crossroads in American democracy.

As I was reading through the newspaper articles for this piece, I kept circling back to a recent pop culture event that got everyone talking: Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl LIX Halftime Show. Like Billie Holiday’s performance of “Strange Fruit,” Kendrick’s show was a sign of the times. Many noted that it was the Blackest Super Bowl of all time: Jon Batiste sang the national anthem to kick off the game; Kendrik showed up with Black icons Samuel L. Jackson, playing Uncle Sam, and Serena Williams, crip-walking; the Philadelphia Eagles, a football team from a historically Black city, won the game handily against the favored Kansas City Chiefs; and Trump skulked away on Air Force One before the game was even over.

It was a small victory in the ongoing culture war. The performance, though understated, was about more than just celebrating a diss track aimed at Drake, persona non grata. The signs were there if you knew how to read them. Kendrick Lamar won a Pulitzer Prize for a reason. His backup dancers, Black men and women, were decked out in baggy jumpsuits, reminiscent of prison uniforms, only in the colors red, white, and blue. When the dancers converged on the steps around Kendrick, their bodies morphed into the American flag. Uncle Sam was, well, Black, a subversive twist on a classic American symbol. And in an unplanned act of symbolism, one of the dancers waved Sudanese and Palestinian flags while standing on top of a car (he was apparently tackled and arrested after the show, but charges were later dropped).

Before Kendrick launched into his mega-hit “Not Like Us,” he busted out a few new verses: “It’s a cultural divide, I’ma get it on the floor. 40 acres and a mule, this is bigger than the music. They tried to rig the game, but you can’t fake influence.” 40 acres and a mule references the Special Field Orders issued by General William T. Sherman during the Civil War, which were supposed to give every freed Black family 40 acres and a mule so that they could begin to build their new lives. Unfortunately, it never came to fruition. The order was repealed by President Lincoln’s successor and many of the families that did receive land had it taken away. “They tried to rig the game”—the game of life, the game of survival as a Black American. Kendrick is pointing to the fact that “the Great American Game” has never been fair.

The Super Bowl LIX Halftime Show was a showdown between the hard power of a government set on disenfranchising Black people and anyone who would disagree with them VERSUS the soft power of a world-renowned artist, perhaps the greatest rapper of all time—“you can’t fake influence”—who wants us to wake up and stand up to the bullshit.

In politically fraught times like these, I have often found myself looking to Black artists, whether it’s Beyoncé or Donald Glover or Kendrick, as a north star, for their ability to speak truth to power, for that kick in the pants that tells us to dig in and keep fighting. It’s not a fair burden to bear—that they should always have to be the ones to wake us from our complacent slumber—but I’m grateful for their art. “Not Like Us” has transcended its original foe; it’s now a rallying cry in the political arena pushing back against the wannabe-fascists in power.

Similarly, when Black Hollywood got together in 1942 to support Chinese refugees and the fight against fascism, they were sending a message not only to the Chinese American community at home and our allies in China abroad, but to the entire country at large. And I’m sure that message was not lost on Anna May Wong.

Updates in Brief

Want to learn more about Black cinema? Check out Maya Cade’s Black Film Archive. You can find some of the films mentioned in this post here, along with Maya’s descriptions and links to stream them. She also writes this Substack newsletter.

Last month I got to interview playwright Philip Chung about his work for The Amp. He’s written two plays about Asian Americans in early Hollywood: Unbroken Blossoms and My Man Kono. I had the chance to attend a performance of the latter here in NYC. The play follows the story of Toraichi Kono, a Japanese American man who served as Charlie Chaplin’s valet and was later targeted by the US government as a potential spy during WWI. He was never convicted but the accusations destroyed his life. It’s an important piece of Asian American history and a deeply moving story. After the performance, I joined a panel with Philip and Chaplin expert Michael Cartellone where I spoke about AMW and other Asian Americans in early Hollywood.

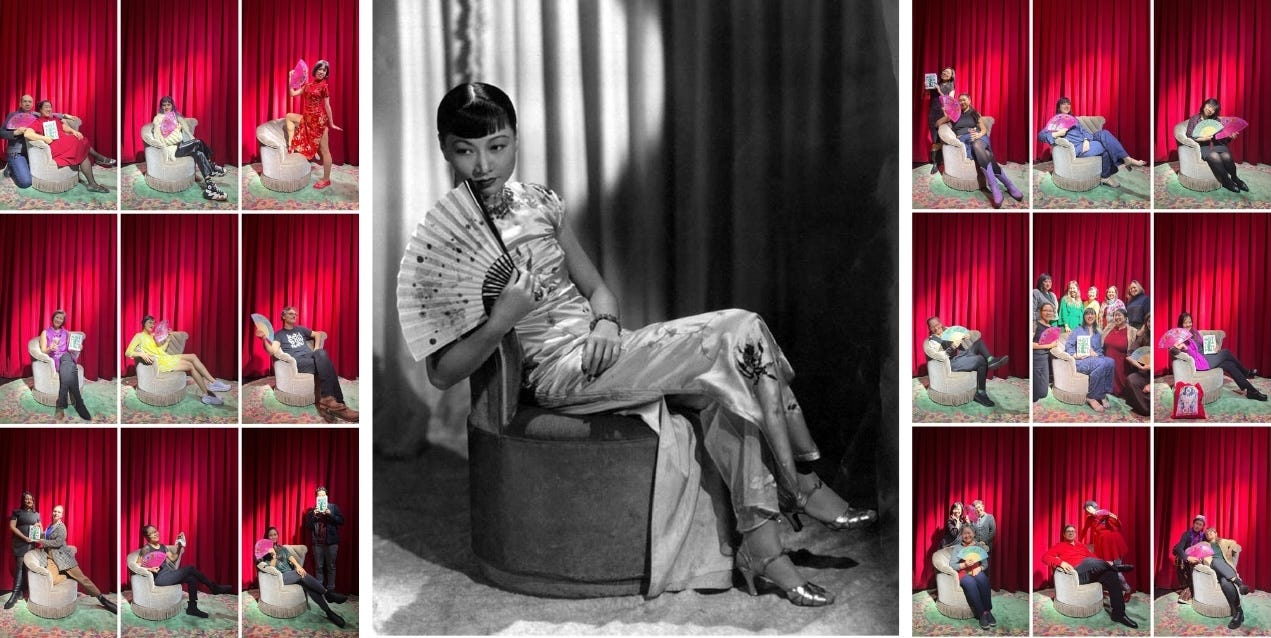

This past week marked the one-year anniversary of Not Your China Doll! To celebrate, I looked back on the dreamy party I threw at Red Pavilion in Bushwick, where the art deco design made it feel like we’d been transported back to Shanghai 1936. One of the highlights of the evening was the photo moment my friend Charlene Wang de Chen, a professional set decorator, created based on a classic image of Anna May Wong—where she’s holding a fan just so and wearing one of her gorgeous, custom-made cheongsams. For the curious, Charlene wrote about how she brought this picture to life on her website. Thank you, Charlene, for making this night so special.

Guests took a turn at recreating AMW’s pose (which gives you a new appreciation for just how hard it is to look that good even when you’re naturally endowed with movie star looks). IMHO, the results were pretty spectacular. I’m still impressed with how everyone brought their A game. They knew the assignment!

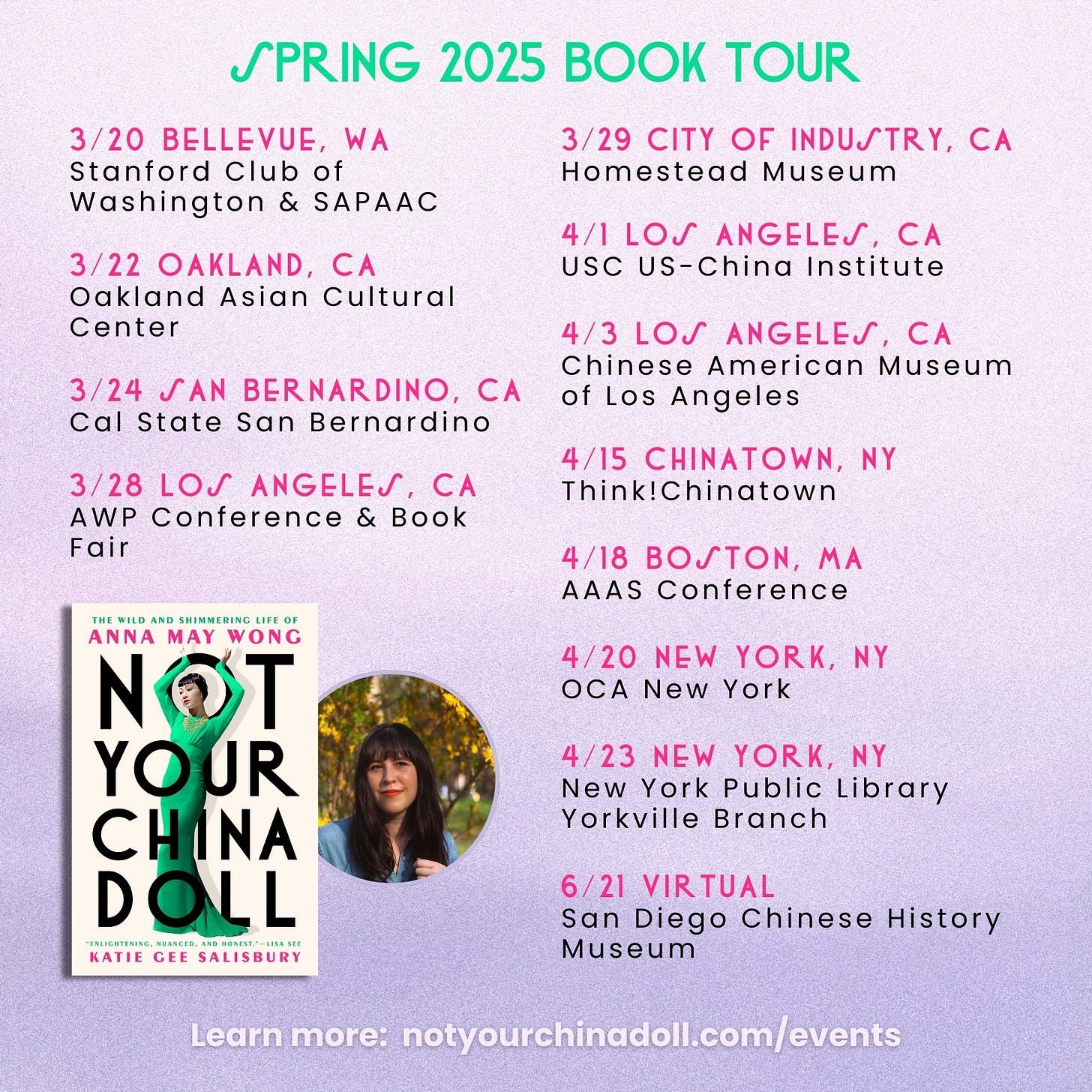

Upcoming Events

March 20, 6:30 pm - Stanford Club of Washington & SAPAAC

Bellevue, WA

Register

March 22, 1 pm - Oakland Asian Cultural Center

Oakland, CA

Register

March 24, 1 pm - Cal State San Bernardino

San Bernardino, CA

Learn more

March 28, 1:45 pm - AWP Conference

Los Angeles Convention Center, Los Angeles, CA

Learn more

March 29, 2 pm - Homestead Museum

City of Industry, CA

Register

April 1, 4 pm - USC US-China Institute

Los Angeles, CA

Register

April 3, 6:30 pm - Screening of The Toll of the Sea at the Chinese American Museum

Los Angeles, CA

Register

I love your writing and also they way you show up with receipts! KGS plays no games. Loved your book!

A beautiful and powerful read.