Young Hollywood Was Asian

the playboys, half-castes, outsiders, and sirens who made motion pictures

Another year, another badass Asian film becomes the unexpected darling of arthouse cinemas across the country and takes the film world by surprise. Since the release of Crazy Rich Asians in 2018, every new release that centers around Asian or Asian American stories has felt like winning another chip at the craps table. Little by little, chip by chip, we are amassing proof not only that there is a place for Asians in Hollywood, but also that movies can be spectacularly successful when Asians act, write, and direct them.

Everything Everywhere All at Once, a low-budget indie production brought to life by the visionary team Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert (aka the Daniels), is the latest of the bunch and it just crossed the $20 million mark in revenue. If one day we decide to cash in our stockpile of chips, will Hollywood stop making Asians jump through endless hoops to make it on screen and into writing rooms?

Of course, we shouldn’t have to prove ourselves, and the fact that we do says a lot about how white supremacy still dominates America in the most unconscious yet persistent ways. Many have doubted, even today, whether Asians/Asian Americans are charismatic enough, creative enough, human enough to be cast in leading roles or to carry a story that does not revolve around a majority white cast. Anna May Wong’s career, which began in 1919 when she was fourteen, proves that this is simply not true.

Interestingly, one of the things I have discovered in the course of researching AMW’s life is that Asians/Asian Americans were an integral part of early Hollywood. Whatever you may have heard, we were there from the very beginning. And the reason that was even possible is because the people who built the film industry in Los Angeles, as I write in my book, were a band of outsiders.

The upright Christians and Midwestern folk who thought they’d discovered their own personal Eden in Southern California in the late 1800s were thrown into a tizzy when studios Back East started sending packs of actors, directors, and cameramen to Los Angeles circa 1910. Residents were disturbed and outraged over those “damn flicker outfits” and wanted nothing to do with the movie-making weirdos who showed up on trolleys and in parks wearing ridiculous costumes with greasepaint smeared on their faces. Many actors and screenwriters who arrived in those days later recalled with a laugh the signs they saw posted at boarding houses: “No Jews, actors, or dogs allowed.”

It’s hard to imagine today, when film, television, YouTube, TikTok, etc. are a ubiquitous presence in the media and entertainment landscape, but motion pictures were very much still a speculative technology and nascent industry at the turn of the 20th century. People questioned whether the “flickers,” as they were dubbed, would ever amount to more than one-reel melodramas and news flashes, a cheap form of entertainment that the uncultured masses paid a nickel to watch in rundown, sometimes seedy theaters. “Legitimate” actors from the New York theater world wouldn’t be caught dead appearing in a movie unless they were down on their luck and desperate for a pay day. The only reason Mary Pickford, who considered herself a Belasco actress, entered the movie business was because she was already a child actor supporting her mother and siblings, and she realized she could make a lot more money working in pictures than on the stage.

Young Hollywood was the Wild West. Nobody with money or prestige was rushing to California to work in motion pictures, at least not yet, which meant the barriers to entry were pretty low to non-existent. California had a sizable Chinese population due to the many immigrants who had come to America during the Gold Rush and worked on the railroad, opened up laundries, taken jobs as domestic servants, or built prosperous small businesses. The West Coast’s proximity to Asia also made it a popular point of entry for those sailing from East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Islands. It’s not a stretch to think that some of these people might get mixed up in the movie business when it sprouted up overnight in their backyard.

In honor of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, I’m sharing a working crib sheet of some of the Asians in early Hollywood that I’ve come across. You’ve likely heard of some of these personalities before or read about them in previous posts. Others will hopefully be as utterly surprising and fascinating to you as they were to me when I first learned of their existence.

There are actually more Asians from Hollywood’s early days than I can list here. Further names that come to mind are Keye Luke, Sojin Kamiyama, Esther Eng, H. S. Newsreel, Toshia Mori, and Elena Jurado, to name a few. Past dispatches of Half-Caste Woman have also highlighted Sadakichi Hartmann and Jue Quon Tai. So consider this an initial attempt at documenting this intriguing and diverse group. And if I’ve missed one of your favorites, tell me about them in the comments!

p.s. Because this edition of the newsletter is so lengthy, it may appear truncated in your email client. Click here to read the full post in your browser.

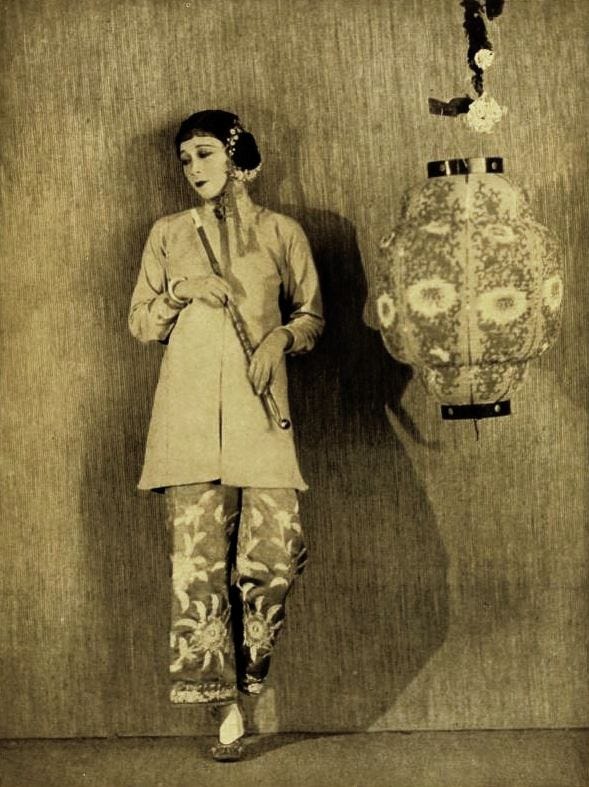

Sessue Hayakawa

In 1915, the same year D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation was released and convinced many that the cinema was a compelling and profitable art form, Sessue Hayakawa, a failed naval recruit from Japan who had wandered about California doing odd jobs, titillated audiences with his breakout role in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Cheat. Hayakawa was the OG Asian in Hollywood, and not only that, his devilish good looks won him a place in film history as the first bonafide heartthrob, predating Rudolph Valentino’s star status by six years.

Women across America fell hard for this new and exotic screen idol. Japanese photographer Miyatake Toyo noted that “White women were willing to give themselves to a Japanese man,” and he recounted a story to illustrate his point: “When Sessue was getting out of his limousine in front of a theater of a premiere showing, he grimaced a little because there was a puddle. Then, dozens of female fans surrounding his car fell over one another to spread their fur coats at his feet.”

Hayakawa lived extravagantly—his Hollywood mansion was often referred to as “the Castle”—and had a reputation for being a playboy. Despite his early success in silent films and launching his own production company, his popularity dried up by the early 1920s as anti-Japanese sentiment increased in the U.S. He left Hollywood to do live theater, make films in Europe, and eventually returned to Japan.

In 1931, he came back to Hollywood after a 10-year absence and accepted a role in Daughter of the Dragon. Though he played the good guy and Anna May Wong’s love interest, the film was his first talkie and his heavy accent was halting at times. Paramount billed him last, after AMW and Warner Oland who played the notorious Dr. Fu Manchu in yellowface. Hayakawa eventually staged his third act as a memorable Japanese military officer in The Bridge on the River Kwai in 1957 and was nominated for an Academy Award.

James Wong Howe

A highly respected cinematographer and the first Asian American to win an Academy Award, James Wong Howe had to overcome numerous challenges to practice his craft. Strangely enough, it was boxing that led him to a career in the pictures. He left Guangzhou, China, at the age of five and immigrated to Pasco, Washington, where his dad had established a general store.

He got picked on a lot as a kid as one of the only Chinese in a majority white town. His first grammar school teacher quit when she realized there was a Chinese boy among her students. It wasn’t long before Jimmie learned how to fight back against his bullies with his fists. By high school, he was winning amateur boxing competitions. At the same time, he got a Kodak Brownie camera by collecting bottles for the owner of the local drugstore. The first photographs he took were of his family, but still unfamiliar with the camera, he accidentally framed the photos so that everyone looked like their heads were cut off. This greatly disturbed his father.

After high school, he traveled down the West Coast, scraping by on various jobs until he landed in Los Angeles. One day he happened to pass by a film crew shooting on the street and someone called out to him. It was an old sparring partner from back in Washington. He told Jimmie about the easy money he was making operating a hand crank camera and soon he was off to the races too.

Alvin Wykoff at Lasky Studios gave Jimmie his first job in the movies, sweeping up the camera room. Little by little he worked his way up to assistant cameraman, then second cameraman, and finally chief cameraman. It wasn’t easy, though. Some crew members refused to work for a Chinese man; others claimed he wouldn’t be able to carry the camera equipment because of his diminutive height; some simply called him “Chinaman.”

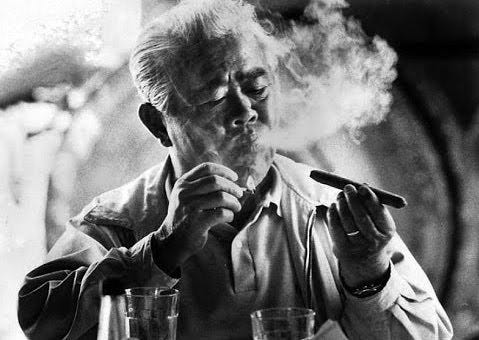

Beyond his natural talent as a cinematographer, two things helped launch his career. The first was Cecil B. DeMille who took a liking to Jimmie while shooting a Gloria Swanson picture. Howe biographer Todd Rainsberger writes that DeMille sat down to watch the dailies and saw footage of Jimmie “wearing a gaudy floral shirt and clenching a big black cigar in his teeth” as he clapped the slate shut for the camera. DeMille laughed and said, “Where’d you get him? I like his face. Keep him with me.”

The second lucky break was when actress Mary Miles Minter asked Jimmie to make some portraits of her, which he often did to earn extra money. Through some ingenious experimentation, he figured out how to photograph Minter without washing out her crystal clear eyes—a recurring problem for most blue-eyed actresses in those days since the film stock that was used regularly failed to pick up the color blue. Suddenly, the Chinese cameraman who knew how to capture blue eyes was in demand.

Jimmie was friends with Anna May and they worked together on the films Peter Pan (1924) and The Alaskan (1924). He married the writer Sanora Babb, a white woman, in France where it was legal to do so, but the couple had to live separately for the first decade of their marriage because of laws criminalizing interracial relationships in the U.S. Despite his stellar reputation throughout Hollywood, Howe couldn’t garner enough support or funding to direct a film adaptation of Lao She’s novel Rickshaw Boy. However, b-roll footage he took on a yearlong trip to China in the late 1920s was eventually used as background in Joseph von Sternberg’s Shanghai Express (1932). In 1953, he directed a feature film about the Harlem Globetrotters and their founder Abe Saperstein called Go, Man, Go. Over the course of his career, he earned 10 Oscar nominations for cinematography and won twice for The Rose Tattoo (1955) and Hud (1963).

Etta Lee

“Half Chinese and Wholly Lovely,” ran the title of a profile of actress Etta Lee in Motion Picture Classic in June 1923. Lee’s father was a Chinese physician and her mother a French woman. She grew up in Honolulu, Hawaii, and earned both a university degree and a teacher’s certificate. She was supposedly teaching at a school for “half caste children” like her when she met a movie director’s wife at a party, and so started her career in the pictures.

In the 1920s, she played a number of supporting roles with big name stars like Douglas Fairbanks and Norma Talmadge, and also appeared in several films with AMW, including The Toll of the Sea (1922), The Thief of Bagdad (1924), and The Chinese Parrot (1927). Writer Victoria Linchong notes that Lee’s biggest role came in 1923’s controversial film The Untameable, in which “she plays the loving and possibly lesbian servant of a woman who develops a split personality after being hypnotized.”

Like AMW, her hybrid identity—Chinese, American, and European all at once—fascinated the press, to the point of distraction. Reporter Barrett Clark spends the first two paragraphs of his profile in Motion Picture Classic bemoaning the fact that Etta Lee lacks an evocative Chinese name and says she ought to be called “The Breath of the Dawn.” During their interview, he challenges her to say something in Chinese, but Lee demurs because she no longer remembers how to speak the language, though she adds: “I am awfully proud of my Chinese blood tho. It gives me a little thrill when I hear some one say: ‘She looks Chinese.’”

Lee lived modestly on the outskirts of Los Angeles and continued substitute teaching in between movie gigs to pay the bills. Despite predictions that she would have a bright career in the pictures, Etta Lee never progressed much past bit parts and exoticized background roles. She married radio news commentator Frank Brown in 1932 and retired from the movie business with 18 credits to her name.

Moon Kwan

Born in Guangzhou, China, and raised in San Francisco, Moon Kwan arrived in Los Angeles in 1915 with aspirations of becoming a filmmaker. There, he attended a film training school and picked up work as a writer, cook, and extra in Hollywood. Many also knew him as a poet. His knowledge of China and Chinese literature got him noticed—the 1910s and 20s produced a surprising number of films with Orientalist themes—and he soon had the chance to make his mark in Hollywood as an advisor on D. W. Griffith’s film Broken Blossoms (1919). The now classic silent film tells the story of forbidden love in London’s Limehouse district between a benevolent Chinese man and a young English girl seeking to escape her abusive father.

Kwan returned to China in 1921, where he set up a film company in Nantong, taught scriptwriting and acting, and also began directing films of his own. Years later back in Hollywood, he consulted on the film Mr. Wu (1927) starring Lon Chaney in yellowface and Anna May Wong in a supporting role. AMW, Moon Kwan, and James Wong Howe were all friends and together hosted a Chinese New Year dinner in 1927 for the Year of the Rabbit.

Kwan’s most important achievement, however, was co-founding Grandview Film Company with partner Joe Chiu in Hong Kong in 1935. According to film historian Law Car, Grandview was “the first big film studio in Hong Kong modeled along Hollywood lines.” The studio produced 65 films over the next decade, producing the first all-Chinese cast, Chinese-language films depicting the everyday lives of Chinese Americans and distributing them throughout Chinatowns across America.

Winnifred Eaton

There is so much I have yet to learn about Winnifred Eaton. A book of her writing, which includes the essay “A Half Caste,” along with a biography written by her granddaughter Diana Birchall are currently sitting on my bookshelf, nearly untouched. (Yet I’m already yearning for a beautifully bound first edition of one of her novels.) She is a fascinating character and deserves a perfunctory mention here.

As the title of her essay suggests, Winnifred Eaton was a woman of mixed Asian descent; her father was an English artist and her mother a Chinese emigrant. She grew up one of fourteen children in Montreal, Canada, but she harbored big ambitions from her earliest days. “Down in my heart there was the deep-rooted conviction, which nothing in the world could shake, that I was one of the exceptional human beings of the world, that I was destined to do things worth while. People were going to hear of me some day,” Eaton later wrote in her autobiographical novel Me.

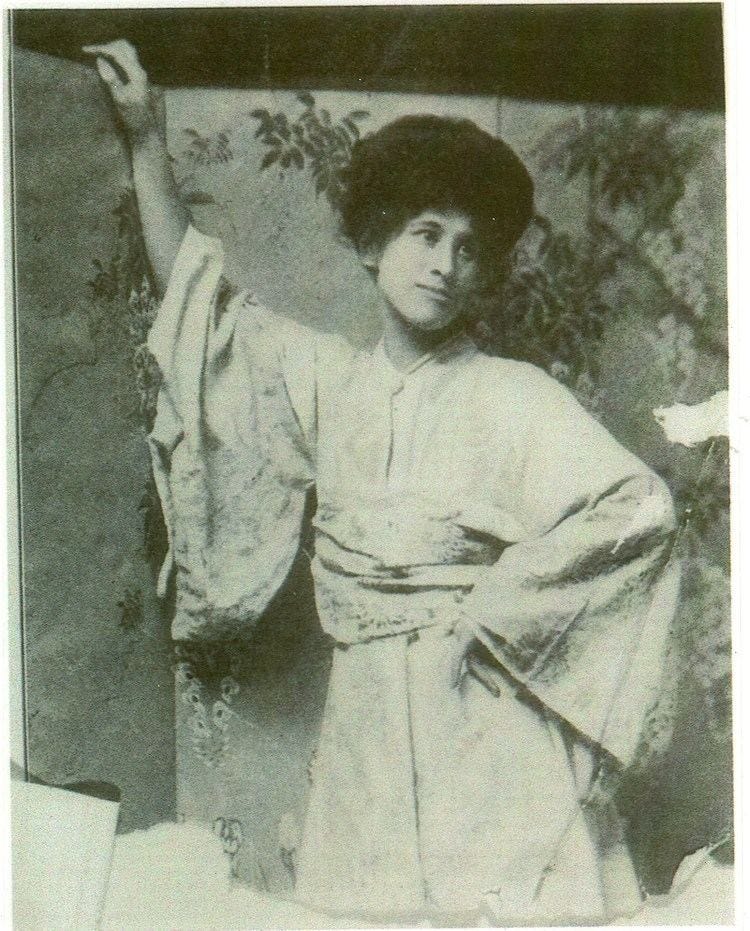

Unlike her older sister, Edith Eaton, who wrote under the pen name Sui Sin Far and purposefully championed the Chinese in her work as a response to anti-Chinese sentiments, Winnifred found herself drawn to Japanese culture. She somewhat subversively styled herself as a Japanese woman named Onoto Watanna and began publishing romance stories and novels under her new alter-ego. At the age of twenty-five, she left Montreal for New York and within a year published her second novel, A Japanese Nightingale. Japonisme was in vogue and the book became a great success, eventually selling 200,000 copies (a huge feat even for books today).

In the late 1920s, Winnifred moved to Los Angeles and became a script-writing protege of Carl Leammle at Universal Studios. Her best known screenwriting credit was for the film East Is West (1930) starring Lupe Velez in yellowface as Ming Toy. Eaton’s Hollywood career ended abruptly (why, I have yet to find out). Her work resurfaced in the 1970s, though, when a new generation of writers began to self-identify as Asian Americans. The editors of the 1974 anthology Aiiieeeee!, however, rejected her identity as a mixed-race Asian primarily because of her ruse of impersonating a Japanese woman. It is only recently that scholars have come to acknowledge her as one of the first Asian Americans to publish literary work in the United States.

Philip Ahn

There’s always been something so familiar and approachable, to me at least, about Korean American actor Philip Ahn. He just looks like a nice guy. So it made perfect sense when I learned that he was literally the boy next door while Anna May was growing up at her father’s laundry down the street. (Hat tip to Sam Sweet’s All Night Menu Vol. 4 and to Ed Park for turning me on to it.)

Philip, in fact, was the oldest son of Ahn Chang Ho, also known by his pen name Dosan, the celebrated Korean independence leader who ultimately died at the hands of the Japanese military in occupied Korea in 1938. According to one of the obituaries saved in Philip Ahn’s papers at USC, Philip also held the distinction of being the first Korean American born in Los Angeles in 1905.

As the only two Asian families on the block, Philip and AMW naturally became good friends. When AMW was cast as the Mongol slave in Douglas Fairbanks’s fantasy flick The Thief of Bagdad, Philip could often be seen driving Anna May to and from the Pickford Fairbanks lot on Santa Monica Boulevard. It wasn’t long before he caught Doug’s eye (the producer/actor was on the lookout for exotic types) and was offered a part in the film. But when Philip came home still wearing the makeup from his test shoot, his mother firmly declared, “No son of mine is going to get mixed up with those awful people.” He wasn’t allowed to leave the house for the next three days.

Philip Ahn did eventually make it into the movies, of course, and he had a long, successful career, making 186 appearances in film and television. In the late 1930s, Ahn and AMW teamed up on screen in Daughter of Shanghai (1937) and King of Chinatown (1939). The press tried hard to link the co-stars romantically—“In spite of the fact she says there’s no romance, Anna May Wong is still constantly seen with Philip Ahn,” a Los Angeles Times reporter observed—but these two old friends just laughed it off.

Merle Oberon

Actress Merle Oberon rose to stardom in the 1930s after she was discovered in London by director Alexander Korda who cast her in The Private Life of Henry VIII in 1933. (She and Korda later married in 1939.) Merle progressed to leading lady roles in Hollywood in The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934) and The Dark Angel (1935), but is best known for her role as Cathy alongside Laurence Olivier in William Wyler’s Wuthering Heights (1939). According to her nephew Michael Korda, “her greatest achievement was not in her roles but herself, as Merle Oberon.”

Merle had one big secret and she kept mum about it until the day she died. Her parents weren’t an English couple who just happened to be visiting Tasmania when she was born. In reality, she was the daughter of a South Asian woman and a British engineer stationed in India.

Oberon passed as a white woman all her life. Occasionally, she was cast in Oriental roles and played characters in yellowface/brownface, like she did in Thunder in the East (1934) as Marquise Yorisaka. When the word “exotic” came up in an interview with Hollywood columnist Grace Wilcox, Oberon responded:

To be exotic, I always think of something very lush, something subtly Oriental, a gardenia, a camelia or a rare perfume. Anna May Wong is my idea of an exotic person and the only other one I know to whom the word might apply is Greta Garbo.

When I am described as ‘exotic’ I laugh. I am sure I’m not.

Apparently, this deflection was necessary because “rumors of her Eurasian blood” circulated throughout Hollywood. It’s sad to think Merle spent her whole life pretending to be white, for fear that her ancestry would ruin her career and prevent her from playing romantic leads, just as it had for AMW. After she died in 1989, the somewhat dubious Hollywood biographer Charles Higham exposed her racial background in his book Merle: A Biography of Merle Oberon.

James B. Leong-https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_B._Leong?wprov=sfti1

“The Purple Heart”-Now felt a “significant movie.”

https://m.imdb.com/title/tt0037197/?ref_=m_nm_knf_act_i32

Starred with AMW in “lost film”, “The Silk Bouquet/Dragon Horse”.

Worked w/AMW in “Devil Dancer”.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Devil_Dancer?wprov=sfti1

Link to only photo known of Dragon Horse.

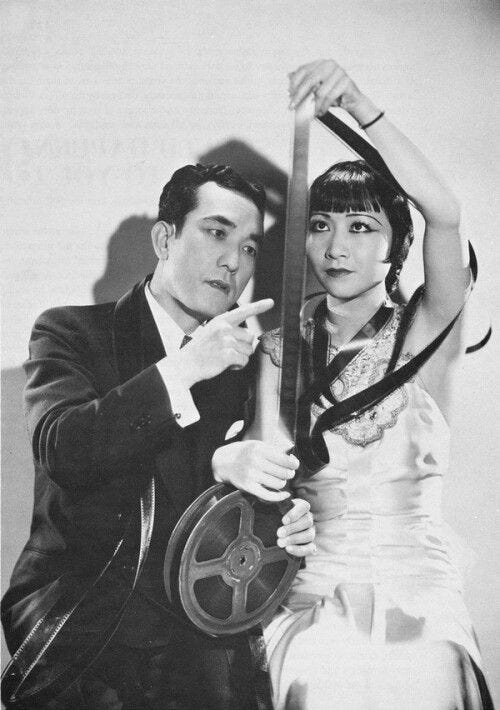

Leong and Wong:

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/a4/95/ee/a495ee6cb373fbc137ec2f73bf007195.jpg