Making Change

Anna May Wong makes her debut on U.S. quarters

Three years ago, almost to the day, I sat down at my childhood desk—a Mondrian-esque IKEA model with bright red and blue drawers—and forced myself to write. I was home in Southern California visiting my parents for the Christmas holidays with the perfect amount of downtime blocked out in my calendar. By that time, I’d been talking about writing a book on Anna May Wong for what felt like an eternity. I’d even written an initial proposal and scored an amazing agent who believed in my book and was eagerly awaiting my sample chapter. And there was the rub.

The time for talking was over. If I wanted a publisher to buy my book, I’d have to start writing it. Gulp. So after seven months of procrastination, I marched myself to that desk and typed out a chapter on Anna May Wong’s arrival in Europe in 1928 and the making of Piccadilly, the film that made her a star in England. Now, three years later, I’ve somehow managed to write more than 120,000 words towards a book that was once merely an idea in my head. Two weeks ago, I turned in a second draft of the manuscript. That I’ve finally done the thing I said I would do feels miraculous, like a magic trick, only I hardly know how I pulled it off.

It reminds me of something Anna May once wrote in a letter to Carl Van Vechten. She was in Berlin at the time, “speaking German like nobody’s business,” and waiting to begin work on her next film—a talkie that would be shot in English and German. Of her new language skills she told Carlo, “It's been most interesting to master what formerly seemed like an impossibility, but we sometimes even surprise ourselves at what we can do.”

I’m grateful for all of you who have been reading along here and cheering me on in person and over the interwebs. (A special thank you to Charlene, a fellow AMW devotee, for taking me out for drinks at the plushest piano bar I’ve ever been to. AMW would definitely approve!) While it’s been quiet here at Half-Caste Woman as I scribbled away at my manuscript, things out in the world of Anna May Wong have been roaring at a fever pitch.

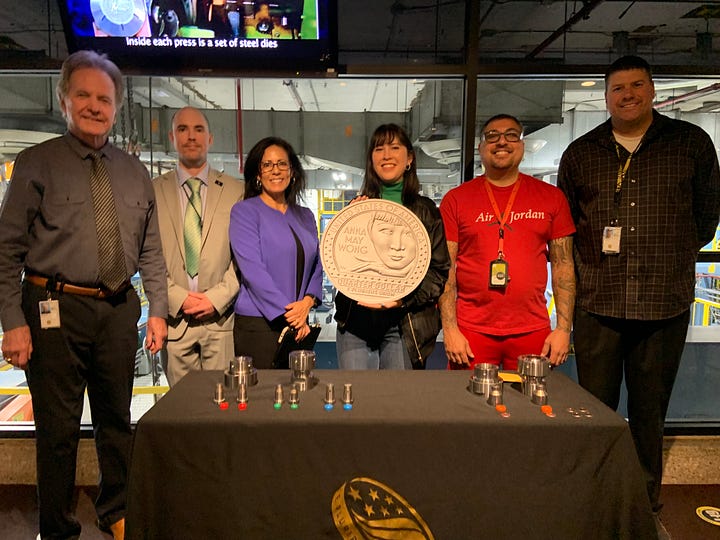

At the end of October, I was lucky enough to get to visit the U.S. Mint at Denver, one of two Mint operations that make all the coins that go into circulation across the country—and yes, it’s also one of the facilities where they mint the Anna May Wong quarters! Jennifer DeBroekert, the Mint’s public affairs officer, and a team of coin experts gave me a tour of the building and a demo of how the casting molds imprint AMW’s face on the smooth, sheets of metal that eventually become quarters. The best part was getting to look down at the production floor while the actual AMW quarters were being made live.

A few elements that make AMW’s quarter special: Artist Emily S. Damstra took her inspiration for the design, as she writes on her blog, from “movie theater marquees from the 1930s,” the kind displayed movie titles and stars’ names in Art Deco style typefaces. The dots around the edges of the coin represent the bulbs that used to light up marquees, but they also conjure up the bright bulbs illuminating dressing room mirrors or even the flashbulbs that used to go off at movie premieres.

Damstra intentionally designed the image to highlight AMW’s beautiful hands, which she so often arranged to dramatic effect. “Anna May Wong was often photographed with her hand or hands glamorously posed near her face,” Emily explains. “With her chin resting on her hand and one finger casually directing attention to her name, this pose might suggest she has been waiting for the kind of recognition that being on a United States coin might finally bring.”

You may also notice that the obverse of the coin features a different illustration of George Washington. The design is by sculptor Laura Gardin Fraser, who submitted her artwork as part of a competition in 1931 to honor the 200th anniversary of George Washington’s birth. Though it didn’t win, the design was popular and has been revived especially for the American Women Quarters program.

The AMW quarters have now made their way to the four corners of the United States. Your best bet for finding one in the wild is to simply buy something with cash and see what you get back in change. Otherwise, try your local bank and ask to withdraw a $10 roll of quarters. Happy hunting!

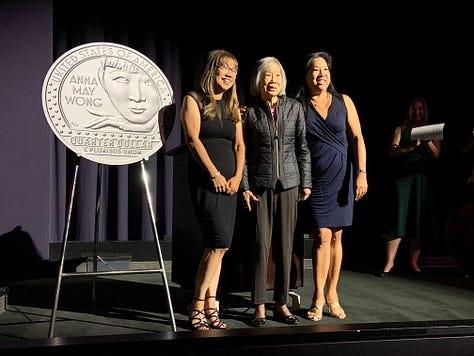

A few weeks after my visit to the Mint, I had the honor of attending a celebration at Paramount Pictures in Los Angeles to kick-off the launch of the Anna May Wong quarter, hosted by the U.S. Mint along with the Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative and the National Women’s History Museum. It was such a thrill getting to walk past Paramount’s famous gates and to see AMW’s old stomping grounds, the studio where she made most of her Hollywood movies.

In attendance that night was the Director of the U.S. Mint, Ventris Gibson, who I interviewed in my piece for Vanity Fair and who also deserves snaps for being the first African American woman to serve in her role; Nina Yang Bongiovi, the producer collaborating with Gemma Chan on the AMW biopic; as well as Anna May Wong’s family, including her niece Anna Wong, who spoke about what it has meant for her aunt’s legacy be honored in this way.

A number of people spoke about the historic nature of Anna May Wong’s career and her immortalization on U.S. currency. I had the pleasure of saying a few words about AMW to the theater of 300+ people and introducing the evening’s film, Shanghai Express. But the words of Gay Yuen, Chair of the Board of Directors and Advisory Council for the Chinese American Museum of Los Angeles, were the most poignant.

Gay kindly put her remarks down in writing so that I could share them with you all here:

I was struck by the beauty of Anna May Wong’s Chinese name (黃柳霜). Wong is her surname. Her given name in Cantonese is Lau-soeng, meaning the frost on the willow tree. Her name evokes an image of a cold winter landscape, with willow trees growing along the banks of a lake, their leaves heavily bent from last evening’s snow storm. These are beautiful elements often found in traditional Chinese paintings. It’s a name that conjures up feelings of melancholy, sadness, and coldness. I can guess that whoever gave Anna May her Chinese name (her grandfather?) was a learned man, maybe even a Confucius educated scholar. It’s an uncommon name that is sophisticated, thoughtful, and ethereal.

After learning more about Anna May Wong’s life story, especially her treatment in a racist Hollywood, the name given to her seems even more appropriate. The insults and pass-overs by Hollywood must have cut through her like the cold snow of a winter’s night. The willow tree in Chinese tradition is allegorical to sadness and the shedding of tears. Not only did her ancestors give her the name of the Willow, they even emphasized that it is a frost/snow-laden willow. Did her ancestors already know the tough life challenges that she was going to encounter?

Gay’s words leave us with the stunning image of a willow tree bent under the weight of winter frost, and yet still the willow perseveres until springtime when its leaves grow strong and green again. It’s a powerful metaphor for the many seasons of hardship and rebirth that AMW went through in life, and even now as her legacy soars once again.

With the book nearly finished, I’m already bubbling with ideas for stories I’d like to share with you all in the coming year when Half-Caste Woman will make a return to more meaty essays. There’s so much material that just didn’t fit in the manuscript and lots of other tangents I’d love to explore in more detail. So stay tuned. Until then, enjoy Anna May Wong’s 1933 holiday card—a whimsical lithograph chronicling her European vaudeville tour (which I previously mentioned here). Happy Holidays & see you in 2023!

Actually, Laura Gardin Fraser DID win the contest in 1931. Then Treasury Secretary Andrew W. Mellon over-ruled the committees involved and selected John Flanagan's design instead.

Congrats.