I’m referring, of course, to the word “miscegenation.” It’s one that comes up fairly often in my research on Anna May Wong. For the uninitiated, Merriam-Webster defines miscegenation as “a mixture of races,” especially when referring to “marriage, cohabitation, or sexual intercourse between a white person and a member of another race.”

Anna May Wong was born and lived in California, where mestizo culture once flourished under Spanish rule. Although Spanish society was ruled by a racial caste system, it afforded space for mixed unions and their offspring. When California was inducted into the Union in 1850, anti-miscegenation laws were passed almost immediately, criminalizing interracial relationships. In the eyes of many Americans, it was the obligation of the government to regulate who one could and could not love. That may seem like a shocking intrusion into the lives of private citizens to us in the 21st century, but it’s really not that much of a stretch if you think about how recently gay marriage was legalized in 2015. The entry for miscegenation in the Cambridge Dictionary notes, pointedly, that “Anti-miscegenation laws prohibiting interracial sex and marriage predate the Declaration of Independence by more than a century.”

As a result, AMW’s public and professional life was circumscribed by anti-miscegenation laws and the social mores they upheld. Miscegenation was like a magic wand that allowed Hollywood to overlook AMW for lead roles again and again, and the studios wielded it with abandon.

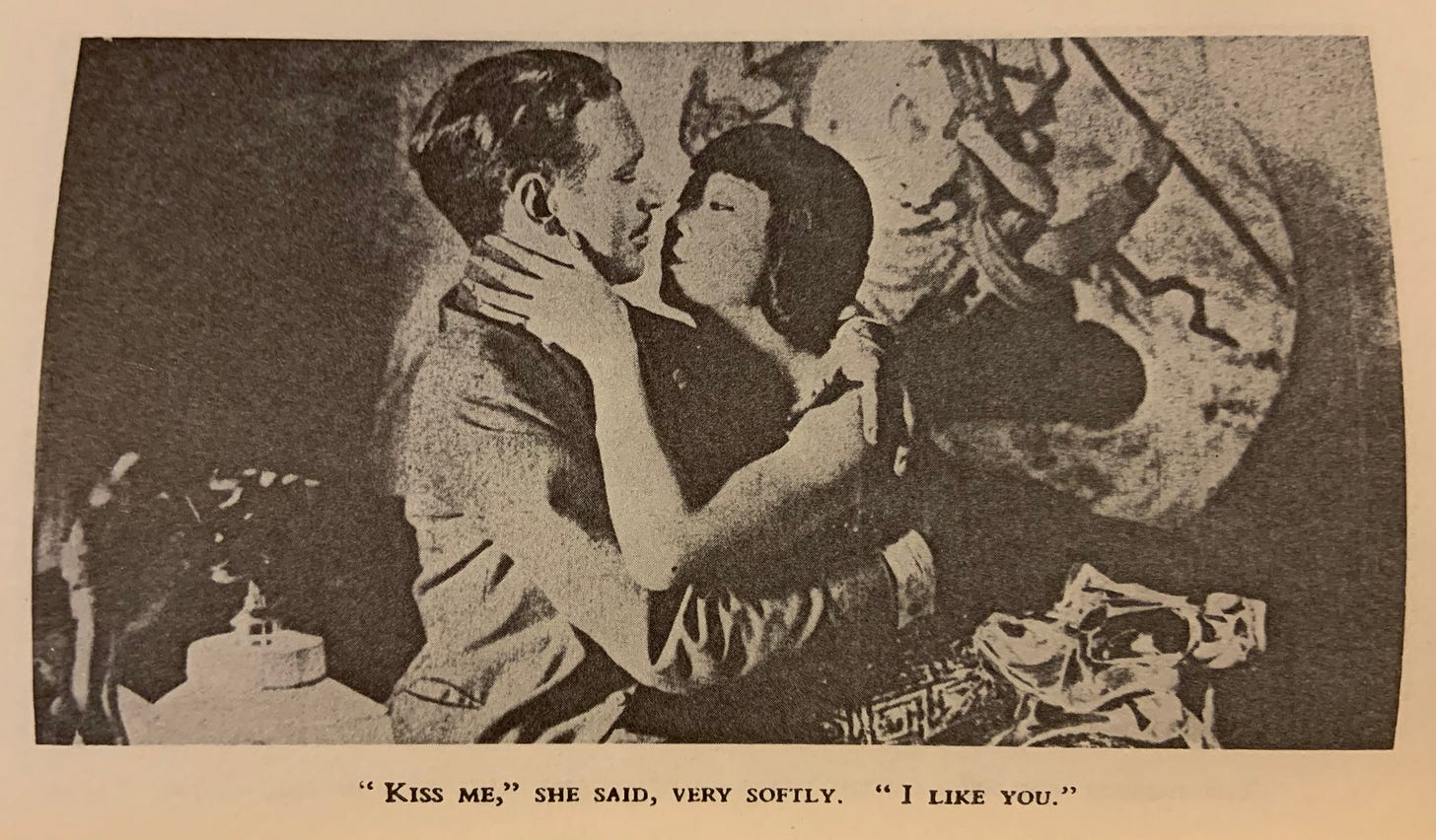

The script calls for the leading lady to kiss her co-star. You cannot kiss a white man on screen. You cannot marry him either, even if it’s just pretend. How about the role of jaded mistress? The prostitute with a heart of gold? The jilted mother of an illegitimate mixed race child? Oh, and by the way, your character dies in the end by drowning/gunshot/dagger to the heart.

Ironically, at the same time that the Hays Code prohibited representations of miscegenation in motion pictures, Hollywood was obsessed with eating from the forbidden fruit. It came as close as it dared to committing this mortal sin in pre-code films like Broken Blossoms (1919) and The Toll of the Sea (1922, featuring AMW in her first lead role), and even in later films like The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1932). The fear of miscegenation gave studio execs a ready excuse, when it suited them, to explain away why AMW could not be cast in such and such a role.

When MGM was casting the part of O-Lan, the female lead in The Good Earth, they argued that AMW could not take on the role because the male lead had already been given to Paul Muni, an Austro-Hungarian actor who would play Wang Lung in yellowface. How meta is that? A Chinese actress was not allowed to play a Chinese woman because in the film she would be married to a Chinese man being played by a white actor. Only a white actress could safely assume the role, otherwise the studio risked giving the film a whiff of miscegenation and thereby lowering “the moral standards of those who saw it.”

In her actual life, AMW never married, but nearly all her known lovers were older white men—directors, writers, cinematographers. Her contemporary and fellow Chinese American, the Academy Award-winning cinematographer James Wong Howe, also grappled with this issue. He sidestepped anti-miscegenation laws by marrying his longtime partner, Sanora Babb, a white woman, in Paris where it was legal. Though Wong Howe and Babb were able to build a life together in the U.S., they still had to navigate society’s disapproval. Many establishments would not serve interracial couples, forcing them to dine in more accommodating restaurants in Chinatown.

The word miscegenation is familiar to me for another reason, though. I am a miscegenation. Or rather the product of it. My mother is Chinese American and my father is Irish American. I’ve never thought of myself in that light, though. Miscegenation is an ugly word. A grating and degrading word. I keep repeating it to put it on blast. But I have always known that were I born in another time and place, I could have been born as evidence of a crime. My existence itself would have been deemed dangerous and subversive, a threat to upright Christian society. Luckily, I came into this world 37 years after anti-miscegenation laws were overturned in California in 1948. However, these laws remained on the books in 16 other states until 1967 when the Supreme Court struck them down once and for all in the case Loving v. Virginia (as depicted in the film Loving).

If miscegenation sounds like a made-up frankenstein word, that’s because it is. As I was gathering my thoughts on this topic and poking around on the internet, I found this illuminating article on JSTOR Daily. The word first appeared in 1864 as the title of a pamphlet: “Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the Races, Applied to the American White Man and Negro.” On its face, the paper appears to advocate for racial mixing as the next objective of the abolitionist movement. “The word is spoken at last,” the pamphlet begins, and goes on to assert that “If any fact is well established in history, it is that the miscegenetic or mixed races are much superior, mentally, physically, and morally, to those pure or unmixed.”

As you can imagine, this theory of “hybrid vigor” was not well received in 1864 as the Civil War neared its conclusion. The backlash was so great that a vigorous campaign against miscegenation was launched in response. Pro-slavery supporters argued that forced marriages between whites and Blacks had been part of Lincoln and the abolitionsts’ agenda all along, striking fear into the hearts of every white American.

The authors of “Miscegenation,” David Goodman Croly and George Wakeman, who remained anonymous to the public, were not phased by the reaction. In fact, they had engineered it. In truth, they were not radical abolitionists but newspapermen at the New York World who opposed abolition and all that came with it. The JSTOR article concludes that Croly and Wakeman set out to troll America and were wildly successful. Their plan worked so well that a hundred years later interracial marriage was still being criminalized.

Despite the restrictions placed upon her, Anna May Wong’s life, career, and relationships defied the codes and conventions of her time. In 1932, she told Hollywood magazine:

A love affair is good if it has beauty. . . . Sincere love is always beautiful, just as a tree is always beautiful. A tree may be twisted and bent, but it is still graceful. A man with a bent body, a woman with a twisted soul, may love more nobly than others who are physically and morally more fortunate.

One wonders if she is referring to her own romantic relationships, which would never be legitimized in the court of public opinion, at least not during her lifetime. She understood this, of course, and embraced it in a sense. On one of her subsequent tours of Europe in 1933, AMW traveled the continent performing her own vaudeville-esque show. Included in her setlist was Noel Coward’s “Half-Caste Woman.” The song laments the unfortunate fate of a Eurasian prostitute, doomed to live a life of penury and isolation because neither race will accept her into its fold. She belongs nowhere.

AMW was ethnically full Chinese, but I can understand why she would wear the scarlet epithet of “half-caste woman” as if it were her own. She was both Chinese and American, her two identities inextricable from one another, and yet neither Americans nor Chinese ever entirely accepted her for who she actually was. AMW was forced to straddle two cultures, not because it was her fate or because all culturally and ethnically mixed people are similarly cursed. No, it was merely the failings of a world not yet expansive enough to contain her exceptional being.

Anna May Wong in Pictures

Anna May Wong looking spiffy in her hat, scarf, and a fresh flower pinned to her coat at the Algonquin Hotel, where she often stayed on trips to New York City.

Stopping in to Say Hello

This month we have a special guest dropping by the newsletter. For the last few months, Mel Guo has been a huge help in assisting me with research, including the somewhat tedious job of trawling through newspaper archives for mentions of AMW and her goings on about town. Here she is to talk about it in her own words—take it away, Mel!

Hello hello! My name is Mel Guo, and I’m a rising senior at Stanford University and an aspiring filmmaker. To me, learning about Anna May Wong’s life and her struggles explores the question: what would it have been like to be the first Chinese American woman in American film 100 years ago? There’s awe and inspiration to be found in the life she led—I only wish that I knew about Anna May when I was growing up.

Digging into the Los Angeles Times archives, it’s clear that she was adored, admired and loved across the board. Frankly, I was surprised. I didn’t expect the first Chinese-American actor in Hollywood to be so popular. Folks fawned over her beauty, her fashion, and her acting. The Los Angeles Times reported every single movie she starred in, lauding her as “extraordinarily brilliant.” LAT even praised her at the expense of Hollywood, saying that “the roles which should have been given to her…were allotted to American girls.”

I didn’t fully understand it until I watched the silent film Piccadilly (1929) that she made in England during one of her extended stays in Europe. I was floored. Anna May Wong’s screen presence is mesmerizing, among the most captivating I’ve ever seen. She plays a dishwasher at a London dance club, where she is given the chance to be the club’s main act. Her facial expressions and body language command the set, the story, and the audience in a way that is difficult to forget.

Having only learned of her recently, there’s this sense of wanting to honor her not only for her brilliance but also for her unfulfilled potential. Anti-miscegenation laws prohibited interracial relationships and the Hays Code banned Anna May Wong from kissing her white costars on screen, preventing her from being cast in leading roles. A big part of me wishes that she were still alive today. I want to see the movies that Anna May Wong would have played, produced, and directed; the stories she would have told.