“You either are a star or you ain't"

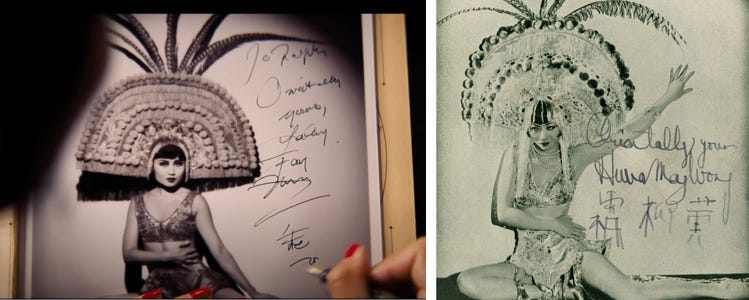

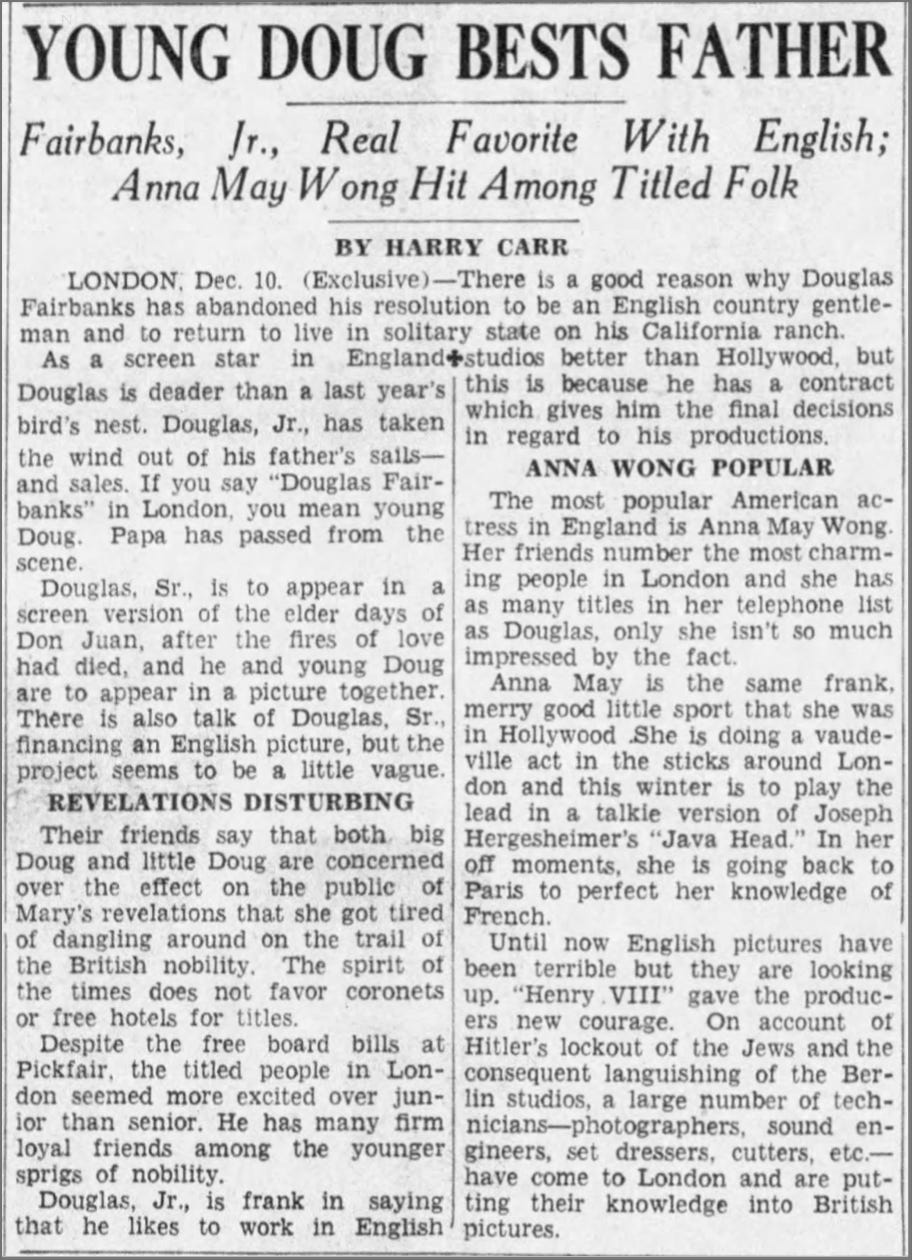

Babylon’s Lady Fay Zhu borrows a page from Anna May Wong

Two no names sit in a dimly lit room crowded with gilded statuary in a famous producer’s opulent Bel Air mansion. The year is 1926. In between snorting lines from powdery white mounds on silver trays, Nellie LaRoy (Margot Robbie) and Manny Torres (Diego Calva) shoot the shit.

Nellie: If you could go anywhere in the whole world, where would you go?

Manny: I’ve always wanted to go on a movie set.

Nellie: Yeah?

Manny: I don’t know. I always wanted to be a part of something bigger, you know?

Nellie: I love that answer!

Manny: Something that lasts, that means something. Something more important than life.

So begins Damien Chazelle’s Babylon, a sentimental yet searing ode to early Hollywood. Drenched in sex, booze, and that eternal longing for fame and success, the film features every outré, insane story ever whispered through the Cahuenga Pass. Elephant shit, flappers driving badly, epic champagne-soaked parties, full frontal nudity, snake wrestling, projectile vomit, a little person bouncing on a pogo-stick-cum-penis effigy—this and more are jam packed into the 3 hour and 9 minute runtime.

We think of Hollywood as a place (where the stars live), but also as an industry (the studios that produce the movies that make the stars). Then there is the idea of Hollywood, an elusive fantasyland, a mirage, an abstraction that conjures up illusions of grandeur: fame, money, immortality. Chazelle’s latest effort attempts to tackle all three.

The director’s first two films, Whiplash (2014) and La La Land (2016), were critical and popular hits, taking home nine Oscars between them, including best director for La La Land. The latter so inspired me, I wrote not one, but two essays on “the fools who dream.” Babylon, however, has not received as favorable a reception. The film cost more than $78 million to make, but has only grossed $65.8 million after six weeks in theaters. And the Rotten Tomatoes meter currently gives it a 55% rating, with an even lower audience score of 52%. According to a consensus of critics, “Babylon's overwhelming muchness is exhausting, but much like the industry it honors, its well-acted, well-crafted glitz and glamour can often be an effective distraction.”

If you can get past the bombastic excess—which is not completely unwarranted, young Hollywood was a wild place—Babylon is actually an excellent primer on the history of moviemaking. As someone who has been steeped in that formative period of Hollywood history while writing my book on Anna May Wong, I appreciated the countless references the film makes to real personalities, film colony gossip, racial and sexual mores, and even the technical challenges the industry faced as the medium evolved to include innovations like sound.

For example, we follow along as Nellie LaRoy arrives at Kinoscope studio, which is little more than a ramshackle ranch littered with open air sets in the middle of the desert. (Early studios used whatever they could to house their sets and equipment, including empty lots, old barns, and the drying yards behind Chinese laundries.) Conservative Christians picket at the studio gates and howl about the evils of the flickers. (The Midwesterners who inhabited Hollywood in the 1910s loathed the movie people who arrived in droves from back East and even petitioned to kick them out.) In her first movie job, Nellie dances provocatively in a bar scene and then is called on to cry for the camera. She wows the crew when she squeezes out genuine tears without the aid of glycerin. (Crying real tears was considered a feat for any actress worth her salt; Anna May Wong similarly earned a reputation for being a skilled wailer.) This silent feature, fashioned after Clara Bow’s The Wild Child (1929), is notably directed by a tough-as-nails woman director in jodhpurs and riding boots. (She wears the standard issue director’s uniform made famous by Cecil B. DeMille; incidentally, there were quite a few women directors in early Hollywood.) Meanwhile, an Asian man operates the crank-operated camera. (A clear nod to award-winning cinematographer James Wong Howe.) All that rich history in one sequence!

The reason I’m especially interested in this film, of course, is because it features a character loosely modeled on Anna May Wong. In the Babylon universe, she’s known as Lady Fay Zhu and brought to life on screen by actress Li Jun Li, who said she gasped with excitement when she was offered the role. While the filmmaker has made a point of saying the character is only meant to be “inspired by” AMW and not a factual representation of her, I can’t help but watch this latest screen depiction and pick apart what’s true from what’s pure whimsy. (Btw, if you want to know who else inspired Babylon’s cast of characters, check out these guides in the NYT and Vulture.)

**SPOILERS UP AHEAD**

Lady Fay Zhu is one of Hollywood’s strivers. Her day job is writing title cards for silent films, but on the side she nurtures the creative performer within. We first meet Lady Fay at producer Don Wallach’s blow-out party inside his castle-like mansion. (You know who else built himself a castle in Hollywood? Sessue Hayakawa.) She steps into the spotlight wearing a slick tuxedo and top hat, as we watch her silhouette puff on a cigarette perched between white-gloved fingers. Lady Fay proceeds to seduce her audience with a tune called “My Girl’s Pussy” (apparently this is an actual song from 1931). She weaves her way through the crowd, titillating them with lines like “I stroke it ev’ry chance I get,” till she lands on a handsome gentleman played by Lewis Tan. She toys with him momentarily, but when she goes in for the kill, she plants a kiss on the beautiful woman sitting next to him—now it’s clear which way Lady Fay Zhu swings.

You couldn’t ask for a more show-stopping entrance. Indeed, the orgy-like party literally stops and is reduced to utter silence in the presence of this commanding woman. Her little party trick of kissing the woman instead of the man is a direct reference to a similar song and dance number in Marlene Dietrich’s Hollywood debut, Morocco (1930), directed by Josef von Sternberg. Marlene pioneered the iconic, gender-bending fashion of dressing in a men’s tuxedo. Many later followed in her footsteps, including Josephine Baker and Anna May Wong, who both incorporated the look into their stage performances in Europe. Lady Fazy Zhu’s cabaret act pays homage to all of these women in a sense, but for me, it’s also a kind of poetic justice. It’s like getting to watch Anna May Wong one-up Marlene in this make-believe performance; she no longer has to play second fiddle to the German siren as she did in Shanghai Express (1932).

Babylon’s portrayal of Lady Fay as queer taps into long standing rumors that AMW not only had relationships with older, married men, but that she also indulged in lesbian affairs. There is something liberating about watching Lady Fay decline the fickle attentions of men and seek love with a similarly independent woman like Nellie. It’s fun to imagine a different kind of life for AMW, but there is little proof that she had female lovers. Although biographers like Graham Hodges have suggested that AMW had dalliances with women, I have yet to find any evidence that firmly supports these claims.

Many speculate that AMW and Marlene Dietrich, who was bisexual, had an affair. I put this very question to Maria Riva, Marlene’s daughter who is now in her nineties and famously wrote a tell-all biography of her mother that includes accounts of her many lovers. Maria responded to my question concisely: “Absolute nonsense. Pals, yes. Lovers? No. Intimate friends in the sense they talked as young women do.” AMW and Marlene were friendly, but they weren’t close. As I’ve written in previous dispatches, I see them more as rivals than as romantic partners. Besides, Marlene was too busy planning secret rendezvous with Josef von Sternberg, Maurice Chevalier, and Mercedes de Acosta.

We next come across Lady Fay in her room above the laundry her parents run. The camera pans past a trove of delicate cheongsams hanging from a pipe in the ceiling as her mother summons her downstairs. There, an angry customer is arguing with her father, but Lady Fay arrives just in time to hand the man an autographed photo to smooth things over. The glamour shot is an exact replica of the headshots Paramount produced for AMW’s starring feature Daughter of the Dragon (1931). This scene felt true to life, since I imagine similar incidents must have played out on more than one occasion at the Sam Kee Laundry as AMW’s profile grew. I also loved getting to see a version of AMW’s home life, which is something I’ve imagined a hundred times over in my own mind.

Still, I do have a few nit-picky notes. Li Jun Li, who plays Lady Fay, speaks Shanghainese in the film, unlike AMW who grew up speaking Cantonese. I suppose this is splitting hairs since Lady Fay is not meant to be AMW per se, but I still wish she could have brushed up on a few words of Cantonese instead. Historically speaking, nearly all Chinese in America at that time were Cantonese. What’s more, a name like Lady Fay Zhu sounds so obviously Mandarin. If they wanted to be true to the period, they probably should have named her Lady Fay Gee. Trust me, I would know. Gee is my mother’s maiden name—and an early Cantonese-based transliteration of the surname 朱, which we English-speakers otherwise know as Chu or Zhu according to Mandarin-based pinyin.

Lady Fay goes on to write the intertitles for Nellie LaRoy’s first picture, which proves to be a hit and makes Nellie a star. From that moment onwards, Lady Fay only has eyes for Nellie. At a raucous pool party at Jack Conrad’s Spanish-style home, Lady Fay sings another one of her sultry songs and uses it as a pretext to kiss Nellie. More drunken, drug-laced madness ensues, and before we know it, a caravan of partygoers has descended upon a rattlesnake in the pitch-black desert. Nellie picks up the snake, declares victory over it, and then is promptly bitten in the neck. Not knowing what to do, everyone runs around hysterically like chickens with their heads cut off. Everyone except Lady Fay Zhu, who, with a tinge of irritation, calmly grabs her switchblade (yes, the Chinese femme fatale always keeps a dagger handy) and cuts the snake in two. She pries the snake’s severed head and fangs from her neck, sucks up the venom, spits it out, and rinses with a swig from her flask. Lady Fay Zhu is the badass who saves the day—a role that AMW very much played in Shanghai Express. Alas, it’s a thankless job. Fay and Nellie become a couple, living a blissful lesbian life together until the gossip rags catch wind of it. The studio, not wanting to further tarnish Nellie’s already questionable reputation, axes Fay from her intertitle job and tells her to fade out of Nellie’s life.

In her final appearance, we see Lady Fay run into Jack Conrad (Brad Pitt). The two are chummy. Lady Fay tells him she’s on her way to Europe to make films for the French studio Pathé. Jack, three divorces under his belt, asks if Lady Fay likes his latest fiancé—she says no. We never learn how the two know each other, but Lady Fay always seems to be the person Jack seeks out when he wants to hear the truth.

Though Jack Conrad is a composite of leading men like John Gilbert, Rudolph Valentino, and Douglas Fairbanks, he reminds me most of the latter. Doug had a jokester demeanor on set and off, but he took his work very seriously. “What happens up on that screen means something,” Jack says in the movie. Doug was a mentor to AMW. He gave her the role that launched her career. But by the time the talkies took over, he was nearing the end of his career and the end of his legendary marriage to Mary Pickford. The couple had presided over the silent era as the King and Queen of Hollywood. But the silent era was over.

At almost the same moment that Fairbanks was fading out of the limelight, AMW’s career took off in Europe, where she made films for UFA in Berlin and British Pictures International in Elstree. She returned to Hollywood as an international star with a Paramount contract in hand. We see the syncopated trajectory of a Hollywood rise and fall reflected in the fates of Jack Conrad and Lady Fay Zhu. By the end of the film, Jack is crestfallen, certain his career is over, while Lady Fay is poised for a breakthrough, her next big thing is just across the Atlantic.

There is a lot that Babylon gets right about Anna May Wong. Damien Chazelle has written her in a way that feels more in line with the woman she truly was—resilient and determined. “Lady Fay is the epitome of strength, grace, and elegance despite all the rejection that she’s faced being an American-born Chinese,” Li Jun Li explained in an interview. Contrast that to Ryan Murphy’s rendition of AMW in his Netflix series Hollywood, which presents her as bitter and defeated.

In the end, however, Lady Fay is still a marginalized character in Babylon. Her role is even smaller in this fictional universe than it was in life. In reality, AMW wasn’t an overlooked hopeful writing title cards behind the scenes; she was a star who captivated audiences from the very beginning. I’m biased, but if you ask me, Anna May Wong is always the main character. So it’s amusing to me that Babylon’s costume designer Mary Zophres was inspired by one of AMW’s spicier portraits, one in which she covers her mostly naked body with a tastefully draped sash. Zophres recreated this look for Nellie LaRoy’s grand entrance into the film. Like Nellie says, “You don’t become a star, honey. You either are one or you ain’t. And I am.”

What I enjoyed most about Babylon was its ambivalent stance towards Hollywood. The film exults in the industry’s zany, ambitious spirit at the same time that it lays bare the blatant racism, sexism, and classism that runs through it. We also see the dark side of celebrity and the toll it exacts. Those who “make it” and reap the rewards of their hard work are undoubtedly the underdog heroes of this story, but stick around long enough, and Hollywood will chew you up and spit you out.

Towards the end of the movie, Jack Conrad shows up at the home of gossip columnist Elinor St. John and demands an explanation for her cover story in Photoplay titled “Is Jack Conrad Through?” Elinor, a mashup of journalist Adela Rogers St. Johns and novelist Elinor Glyn, attempts to soothe Jack’s fall from grace:

I know it hurts. No one asks to be left behind... But in a hundred years, when you and I are long gone, anytime someone threads a frame of yours through a sprocket, you will be alive again. You see what that means? One day every person in every film shot this year will be dead. And one day those films will be pulled out of vaults and all their ghosts will dine together. . . . A child born in fifty years will stumble upon your image flickering on a screen and feel he knows you like a friend, though you breathed your last before he breathed his first. You’ve been given a gift. Be grateful. Your time today is through, but you’ll spend eternity with angels and ghosts.

Her words serve as the film’s final refrain about the power of moviemaking. I’m one of those kids, after all, who saw an image of Anna May Wong long after she had left this earth and felt like some part of me had always known her. If that ain’t magic, I don’t know what is.

It Only Took 95 Years . . .

Oscar nominations were announced last week and to our delight, Everything Everywhere All at Once leads with 11 nominations! The long list of nominees includes Michelle Yeoh, who has made history by becoming the first Asian-identifying woman to be nominated for best actress. What’s with all the modifiers? Well, the first Asian woman to be nominated for best actress dates back to 1935 when Merle Oberon was nominated for her role in The Dark Angel, except that Oberon wasn’t “out” as Asian. As I noted in a previous newsletter, Oberon kept her mixed heritage a secret until she passed in 1979.

Also in the running for Academy Awards this year are Ke Huy Quan for best supporting actor (Data and Short Round were my childhood heroes!), Stephanie Hsu for best supporting actress, and the Daniels for best director. But that’s not all. Actress Hong Chau is nominated for best supporting actress for her role in The Whale, and Domee Shi’s Turning Red is nominated for best animated feature film. Last but not least, the Nobel-prize-winning novelist Kazuo Ishiguro is nominated for his screenplay for Living. As the New York Times put it, 2023 is “a record-setting year for Asian actors.” Anna May Wong would be proud.

I like this article and the history in it.

I did not care at all for the movie--not just for its portrayal of a character who was certainly intended to represent Anna May--because it could represent no one else, and walked out. Not specifically for the "Wong" inspired character. There was some degree of sympathy shown by the director--but...it was a part of it.