The Invention of the Chinese Laundry

how an immigrant group adapted its labor force to survive in a racist system

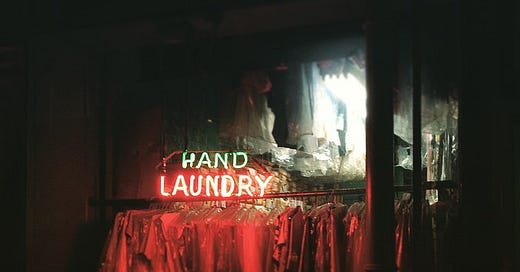

Small businesses have long been the bastion of first-generation immigrants starting out in America and hoping to build a life here. There was a time when Chinese laundries were as common as the corner bodega or mini-mart. Once industrial washing machines came along, though, many hand laundries went the way of the dinosaurs. In their place a new business sprung up: Chinese takeouts.

Oftentimes trends like this have a lot to do with migration patterns and how networks of immigrants leverage resources. In the case of Chinese laundries, the industry was born of a practical strategy to survive in a hostile country and circumvent the racist strictures enforced against Chinese immigrants.

To really understand what I mean, we have to go back to the transcontinental railroad. Sometimes I feel like a broken record because I bring up the railroad so dang often. But the truth is, when it comes to the Chinese in America, immigration law, post-Civil War America, or Manifest Destiny, all roads lead back to the railroad.

Here’s the concentrated orange juice: Chinese laborers made up 90% of Central Pacific’s workforce, were paid considerably less than white laborers, did the most dangerous work including dynamiting their way through the Sierra Nevadas, and paid out of pocket for food and shelter. When the railroad was completed in 1869, thousands of men suddenly found themselves unemployed. The Civil War had left a bitter taste in many people’s mouths, but now that Black people were free, the racial animus that has always been a part of America’s DNA set its sights on a new scapegoat. People were angry and they took that anger out on the Chinese in the West, a territory where the lynch mob was the only law in town.

At times the white majority succeeded in running the Chinese out of town, and a number of Chinese did return to China or were denied re-entry to the U.S. after the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882, but thousands of Chinese men remained (Chinese women had already been effectively banned from entering the U.S. by the 1875 Page Law). They needed work in order to continue sending money home to their families in China and to pay off whatever debt they’d been saddled with to get there in the first place.

Because the vitriol channeled towards Chinese immigrants framed them as usurpers taking away jobs that rightfully belonged to white men, and even more frightfully, luring “good Christian women” to commit miscegenation, it became more and more difficult for Chinese laborers to work in mining, manufacturing, and agriculture. Japanese immigrants were substituted in for labor shortages on farms (an early example in a long history of pitting the Japanese and Chinese against one another in America), while pressure from labor unions led tobacco, shoe, and wooden manufacturers to prohibit Chinese employment in the 1880s.

There were few women in the West, which meant there was a shortage of people to do what was typically considered “women’s work,” such as cooking, cleaning, sewing, and washing. The demand for laundry service became so dire during the early days of the gold rush that miners, both Chinese and white, began sending soiled garments to Hong Kong to be cleaned for the inflated price of $12 for a dozen shirts. It took four months, but that was still exponentially faster than sending it Back East (of course, this was before the transcontinental railroad was completed; you can see why the railroad was revolutionary for its time, right?).

The “feminized” trades were practically the only option left open for Chinese men, which is why so many of them became laundrymen, domestic servants, and cooks. (When my great-grandfather first immigrated to the U.S. from Toisan, China, around 1915, he too worked as a “houseboy” for a wealthy family in Los Angeles.)

Enter the Chinese hand laundry. One enterprising Chinese man, Wah Lee, went into the laundry business as early as 1851, and by 1880 more than three-fourths of all laundries in California were run by Chinese. Anna May Wong’s father was one of them.

In fact, the media loved to make hay out of the fact that AMW was the daughter of a laundryman, sometimes styling her as a “Chinese Cinderella” who played parts in Hollywood movies by day and toiled in the Sam Kee Laundry by night. Studios knew to call the laundry directly, since it doubled as the Wong family residence, whenever they had a part in mind for her. And when reporters came calling, she unabashedly welcomed them in and showed them around. The Los Angeles Times later memorialized Sam Kee Laundry in 1936 as part of a nostalgic illustrated series of “landmarks and out-of-the-way places almost forgotten in the march of progress.” The article itself, however, was riddled with offensive tropes and spurious anecdotes.

Naturally, as someone writing about AMW, I wanted to understand what it was like growing up around the laundry business. Was there a stigma associated with the profession? What kind of challenges, i.e. racism, did her father face as a laundryman? What did other Americans think about Chinese laundries?

It turns out a lot has been written on these very questions.

Moving into “feminized” jobs such as the laundry business may have curbed the wrath the Chinese faced (though they were still accused of taking work away from widows and single women), but the racial aggression directed at them never stopped.

Chinese laundries operated on a ticket system. When a customer came in with dirty washing, they were handed a duplicate ticket matching the one now affixed to their bundle of clothes; in order to retrieve the clean clothes a few days later, they simply had to produce the ticket. “No tickee, no washee” became a popular expression used to mock the Chinese laundryman, a symbol of how he remained “other” in America even as he spent his life, six to seven days a week, scrubbing and ironing and mending the most intimate pieces of clothing for other Americans. Customers complained that they couldn’t read the tickets because they were marked in Chinese. Others showed up without tickets, sometimes intending to steal clothes that weren’t theirs, and threatened violence if their demands weren’t met.

But that was just the tip of the iceberg when it came to dirty tricks. Upon collecting their laundered clothes, some customers would ruthlessly inspect each piece looking for stains, snags, or other imperfections so they could claim a refund. More ingenious were those who dropped off clothing with dye capsules hidden inside, which could ruin an entire batch of laundry by turning it red. Then there were the petty pranks of delinquent children who threw rocks at the windows of Chinese laundries and, in the winter, dirty snowballs at clean clothes hung out to dry.

Lee Chew, a laundryman who lived and worked in both California and New York, wrote about his experiences for The Independent in 1903: “The treatment of the Chinese in this country is all wrong and mean. . . . All Congressmen acknowledge the injustice of the treatment of my people, yet they continue it. They have no backbone. Under the circumstances, how can I call this my home, and how can any one blame me if I take my money and go back to my village in China?”

The thing that fascinates me most is how the law codified this type of behavior, bent and twisted itself in ever more inventive ways to contain, diminish, and antagonize the presence of the Chinese in America. In a country that has wielded the law as an instrument of segregation, disenfranchisement, and outright murder, the existence of such laws targeted at the Chinese should be no surprise. And yet there’s something strangely riveting about just how much energy goes into maintaining racism. It requires dedication, creativity, and a lot of hard work—and that is not a statement of praise.

In my research, I stumbled upon a law review paper that examined numerous cases brought before the U.S. courts involving Chinese laundrymen. All sorts of insane laws were passed to hinder their livelihoods. There were laws against using a pole to carry baskets of laundry on one’s shoulders, zoning restrictions that overnight made the long-established location of a laundry suddenly illegal, licensing laws that required laundry businesses to obtain licenses from city boards and fire wardens who then refused to issue them, and maximum hours laws that restricted the time of day that laundry work could be done. For instance, many laundrymen ran separate businesses from the same shared facilities in order to cover rent; they worked in shifts, one conducting his business from 9 am to 6 pm and the other working through the night from 6 pm to 9 am. Under the maximum hours law, it was illegal to do laundry work after certain hours, so if the police caught you washing and pressing clothes at 8 pm, they could arrest you and haul you off to jail. Arrested for doing your job. Imagine that.

Chinese men were not granted citizenship nor voting rights, even if they had been born in the U.S. Their only recourse was through the courts. Fed up, a few laundrymen banded together, hired lawyers, and fought the unfair charges brought against them. Incredibly, Anna May Wong’s father was involved in one of these cases.

In November 1913, when little Anna May was 8 years old, her father Wong Sam Sing was arrested. He had violated a new ordinance passed in Los Angeles that prohibited “the establishment of laundries in certain districts unless the consent of 60 percent of the property owners has been maintained,” despite the fact that his laundry had sat at the same address for six years. Wong sued the L.A. County clerk and actually won the case in Superior Court. The city appealed and years later Sam Kee v. Wilde was heard once more before the California Supreme Court in 1919, where the decision was ultimately overturned by Judge Paul J. McCormick.

It’s unclear what this result meant practically for Wong and his business, aside from the humiliation, frustration, and lost time and money spent on fighting the ordinance that it must have caused. Sam Kee Laundry remained located at 241 North Figueroa Street through the 1920s. I wonder, though, whether as a young girl AMW understood what was being done to her father and the family business, whether she saw him being handcuffed and dragged away, if this incident, which I have yet to find any record of her mentioning in public, lodged itself in her psyche and weighed on her when she considered her position as the sole Asian American actress of any note.

At the root of all racism is the desire to dehumanize people perceived to be different, and thereby justify any cruel, inhumane treatment of them as their just deserts. This is how you end up with people kidnapped from one continent and enslaved on another. This is how you end up with children in cages. This is how you end up with laundrymen arrested for simply doing their jobs.

In 1921, a reporter named Ben Hecht published a story titled “The Soul of Sing Lee” in the Chicago Daily News. Hecht attempts to paint a sympathetic picture of an aging laundryman named Sing Lee. To my modern eyes, the portrait offered is more pathetic than empathetic; Hecht repeatedly calls his subject an “automaton.” However, there is a twist at the end when Hecht finally engages his subject in conversation. Sing Lee admits to this writer, who has come to editorialize his life in the laundry, that he, too, used to write. Poems, in fact. He recites a poem, translated into English, for his audience:

The sky is young blue.

Many fields wait.

Many people look at young blue sky.

Old people look at young blue sky.

Many birds fly.

At night moon comes and young blue sky is old.

Many young people look at old sky.

Sing Lee, it turns out, contains multitudes. Just like you or I.

AMW in Pictures

Anna May Wong as a scullery maid (aka dishwasher) who dreams of becoming a dancer, in the British film Piccadilly (1929).

In Memoriam

On Saturday I attended a procession in Chinatown to celebrate the incredible life of Corky Lee, affectionately known to many as the “undisputed unofficial Asian American Photographer Laureate.” For nearly five decades, he documented Asian American life and activism and, as Hua Hsu put it in the New Yorker, “helped us see ourselves.” He was a fixture of New York’s Chinatown where everyone knew him on a first-name basis, which is why it’s hard to imagine walking down Mott or Pell Street and not running into him. He was also the son of a laundryman; his father ran a hand laundry in Queens. Corky passed away on January 27, 2021, after battling COVID-19 for several weeks.

There are a number of loving tributes in the New Yorker and the New York Times, on Facebook and Instagram. One of my favorites was a memory shared by Ken Chen, who recalled that Corky once told him, “I’m Asian American, which means I’m a 100% authentic fake.” I was lucky enough to accompany Corky on a train ride from Ogden to Salt Lake City, Utah, during the 150th anniversary of the transcontinental railroad in 2019. I wrote about the experience for Slant’d magazine, but you can go straight to the source and listen to the uncut audio of our conversation here. Rest in power, Corky.