The Magic that Happens When We Tell Our Own Stories

how Anna May Wong’s legacy is coming full circle a century later

Something Mel Guo said a few newsletters ago has been replaying in my head. She wrote that discovering Anna May Wong was a kind of revelation that made her want to honor AMW’s “unfulfilled potential.” She echoed a yearning that I have long harbored: “I want to see the movies that Anna May Wong would have played, produced, and directed; the stories she would have told.”

Usually when people learn the basic outline of AMW’s life, their first reaction is—“Oh, how tragic!” Her career undoubtedly suffered because of pervasive racism and sexism in Hollywood. This is most clearly evidenced by the roles she was typecast in over and over again. Something about being a sexually alluring Asian woman, whether the demure China doll or the wicked Dragon Lady, meant she was doomed to die (we saw this fetishization play out quite literally in Atlanta). In fact, a particular quote from one of her last interviews is oft repeated, when she turned to the reporter and said wryly: “When I die, my epitaph should be: I died a thousand deaths. That was the story of my film career.”

Konstantin Stanislavski, the Russian theatre legend, famously said, “There are no small parts, only small actors.” Anna May Wong made a career out of shimmering in the flimsiest of roles. She became internationally famous playing the Mongol Slave in Douglas Fairbanks’ The Thief of Bagdad (1924). Enough said.

Here’s another example. I rewatched Josef von Sternberg’s Shanghai Express (1932) this past week. The film is a mesmerizing piece of lyrical filmmaking that still delivers nearly 90 years later, and it’s funny too. AMW in the part of Hui Fei, a Chinese coaster (that’s slang for prostitute), is simultaneously of no real consequence and yet also the hero who makes star Marlene Dietrich’s happy ending possible. Although she only appears in a handful of fleeting scenes, Shanghai Express has always been one of my favorite films of hers because she positively smolders every time the camera dares to look at her.

It’s not enough to think about typecasting solely in the context of the individual tragedy suffered at the hands of feeble-minded casting directors. As many of us have been learning over the last year, racism is not merely experienced in personal interactions, racism is a system. There is a reason the same stereotypical parts were routinely offered to AMW. (“So-called ‘sinister’ roles—and I get plenty of them—I don’t like so much,” she once told a reporter.) It’s not just that the people making decisions lacked imagination or worried no one would watch a film with an Asian lead (which, until very recently, were the same excuses being used by studio executives today). They were the wrong people to begin with.

Want something done right? Do it yourself, so the mantra goes. The actor-turned-creative producer has been a staple of Hollywood movie making since the very beginning. The silent era’s biggest stars, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and Charlie Chaplin, made fortunes acting in other studios’ films and wisely put that money towards their own production companies so that they could wield complete creative control over future film projects (the three along with director D. W. Griffith later founded United Artists based on this premise). Countless actors and directors today have continued this tradition. Spike Lee, Will Ferrell, Tyler Perry, Brad Pitt, Will Smith, and Reese Witherspoon’s Hello Sunshine are a few that come to mind.

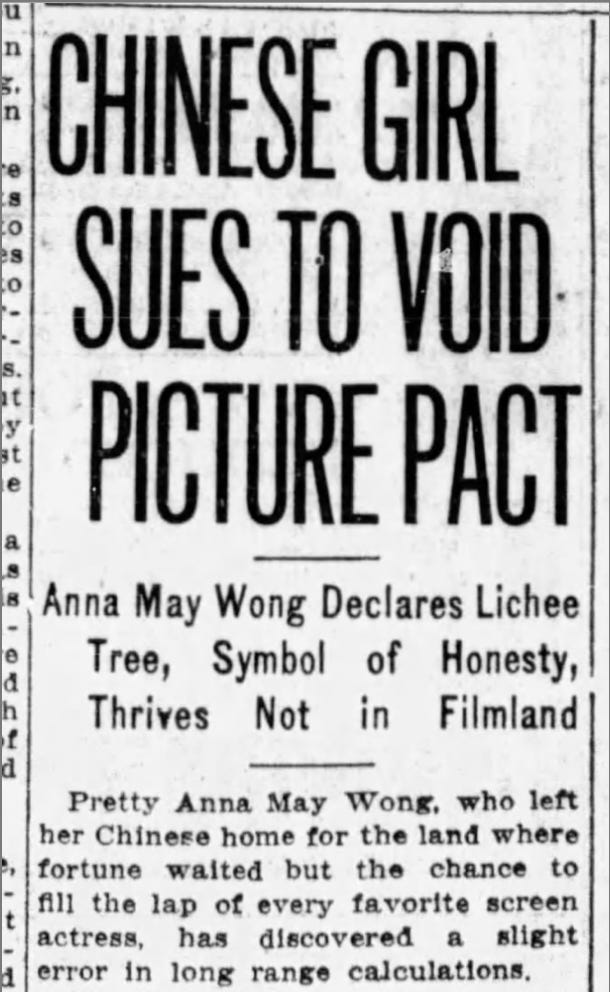

The rush of recognition and fame that came from the success of The Thief of Bagdad led AMW to enter into a partnership with a producer to establish the Anna May Wong Productions Company (my heart skipped a beat the first time I read those words). Her partner promised to secure $400,000 in funding and finance a series of films she planned to make based on Chinese classics (presumably stories like Dream of the Red Chamber and Journey to the West). Instead, the supposed Los Angeles producer used her newly minted name to rack up thousands of dollars in debt. AMW sued and the contract was cancelled. Her production company only ever existed on paper.

She was nineteen when all of this went down. She was paid substantially less for her movie roles compared to her white peers and didn’t have the cash reserves to finance a company on her own. She didn’t have a hard-as-nails stage-mother like Mary Pickford or a savvy businessman husband like Norma Talmadge to look out for her best interests. She came from a working class family that didn’t have the kind of institutional knowledge that prevents one from entering into a $400,000 deal (more than $6 million in today’s money) without the necessary due diligence.

The story repeats itself in different permutations with James Wong Howe and Bruce Lee. Wong Howe, an Oscar-winning cinematographer, had ambitions to direct a film based on Lu Xun’s novel Rickshaw Boy, a modern Chinese classic. Aside from some b-roll shot in China, the film was never made. Bruce Lee, who was already a bonafide star in Hong Kong, struggled to break through in Hollywood (the ESPN docu Be Water does an excellent job of capturing this). He wrote and pitched a treatment for a TV series about a kung fu warrior and his adventures in the Wild West. Studios couldn’t get behind it because they didn’t see how an Asian man could play the lead. Who would want to watch that? A few years later the idea resurfaced as the 1972 series Kung Fu starring David Carradine in yellowface. Lee was never credited.

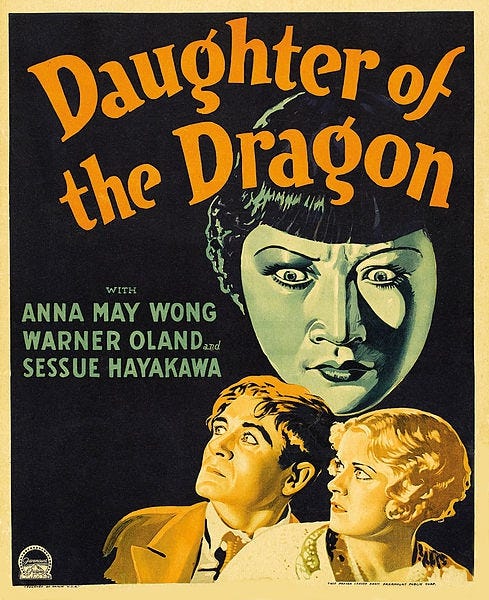

AMW’s dream of developing her own film scripts and then starring in them never died. For a time she employed a writer and friend, Grace Wilcox, to work on scripts for her. Tiring of the vamp roles she played in her youth, AMW restyled herself in her 30s as “a sort of feminine counterpart of Charlie Chan.” Many of her later pictures featured her in detective-like roles. When she took a part in Daughter of Shanghai, she pointedly had the script rewritten so that her character would play a more integral role. In 1951, she became the first Asian American to star in a TV series with The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong, a part that was written specifically for her. And finally, one of her crowning personal achievements was producing and narrating a documentary called Native Land based on footage of her 1936 trip to China, which aired on ABC in 1957.

For someone who was never handed anything on a silver platter, she made out alright. AMW worked until her death in 1961, passing away just weeks before filming on Flower Drum Song, in which she was to play Madam Liang, was set to begin. Her staying power in the film/TV industry is a testament to her tenacity and unwillingness to take no for an answer.

Things have only started to change for Asians and Asian Americans in Hollywood in recent years, but, thankfully, these gains seem to be stacking up and multiplying. It has been a strange time for the AAPI community. On the one hand, we continue to be devastated by increasing violence and vitriol aimed at Asian Americans in this country. On the other, there is power in knowing that our stories are finally getting told on a grand scale.

Crazy Rich Asians crashed opened the floodgates in 2018 (just three years ago) and, as condescending as this sounds, it finally showed Hollywood execs that American audiences will pay to watch a movie about Asians. This didn’t happen by accident. The movie, which was based on the brilliant and hilarious novel by Kevin Kwan, was directed by Jon M. Chu with a screenplay co-written by Adele Lim (who was paid significantly less than her white male co-writer) starring Constance Wu, Henry Golding, Michelle Yeoh, and an international cast of Asian actors. Asians weren’t just on screen, they were also behind the scenes calling the shots. Is it any wonder that we’re better at telling our own stories? (Disney failed to grasp this distinction when it hired a nearly all-white production team to direct and write the live-action Mulan and it tanked.)

When I was growing up in the 90s, there were very few Asian Americans on television or movies or anywhere in the public sphere. The three who instantly come to mind (and who I looked up to) were Olympic skater Michelle Kwan, BD Wong as the astute psychologist on Law & Order: SVU, and Margaret Cho in her groundbreaking show All-American Girl. The Asian American universe was tiny. Thinking back on it now, it’s almost quaint.

But that doesn’t mean I’m not also in awe of Bong Joon-ho’s 2020 Oscar sweep for Parasite. Or still basking in the glow of Sandra Oh’s triumphant 2019 Golden Globes moment when she declared, “It’s an honor just to be Asian.” Or rejoicing for Yuh-Jung Youn’s Academy Award for best supporting actress aka the badass grandma in Minari (her performance brought me to tears and btw, the film was made by Korean Americans).

A few days ago I started bouncing up and down giddily on the couch when I found out HBO Max is picking up Warrior for a third season. Yes, the same Warrior series that Bruce Lee once pitched to deaf ears was quietly unearthed decades later by daughter Shannon Lee and championed by Fast & Furious franchise director Justin Lin.

Nick, my better half, turned to me with surprise, “You seem really excited?” It’s hard to explain, but watching Warrior is not only a history lesson in what life must have been like for early Chinese immigrants arriving in California. It also feels like coming home after trudging on in the long, uncertain journey for representation.

The cast, helmed by Andrew Koji (a fellow halfie) in the lead role of Ah Sahm, is made up of a diverse set of Asian actors. They look like people I know and grew up with, almost uncannily. (James Han, if you’re reading this, you’re a dead ringer for Bolo.) This is what my Asian America looks like.

We will never know what Anna May Wong could have achieved during her lifetime had there been Asian American contemporaries to write and direct projects with more complex and nuanced characters for her. I like to think, though, that she’s smiling down on us at this moment—proud that her legacy is being carried on in a thousand directions at once. Which, if you ask me, is a much more fitting epitaph to be remembered by.

So very well written. Bravo, fellow.

Thank you for this article. I thought Anna May Wong was amazing in the film Piccadilly and it's interesting to see how she was "received" in the UK at the time.