Traveling Back in Time

Red Cars, Los Angeles geography, and Chinese American teenagers with Jennie Liu

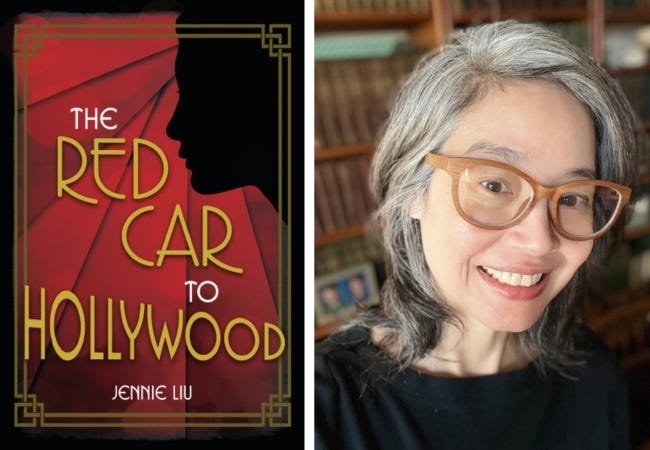

Jennie Liu is the author of four young adult novels, including Like Spilled Water and Girls on the Line. Her latest, The Red Car to Hollywood, follows the misadventures of Ruby Chan, a Chinese American teenager living in 1920s Los Angeles. Ruby gets into hot water when her parents discover she has been dating one of her white classmates from high school. Rather than let her help manage the family’s antique business in Chinatown, her father is convinced he must marry Ruby off to keep her out of trouble and maintain the family’s propriety in the community. Of course, Ruby has other ideas about her future, and along the way she meets Anna May Wong, who is still working in her father’s laundry despite her burgeoning fame as a film star. Ruby and Anna May are two like-minded gals. They have a lot of fun together—and sometimes get into a bit of trouble!

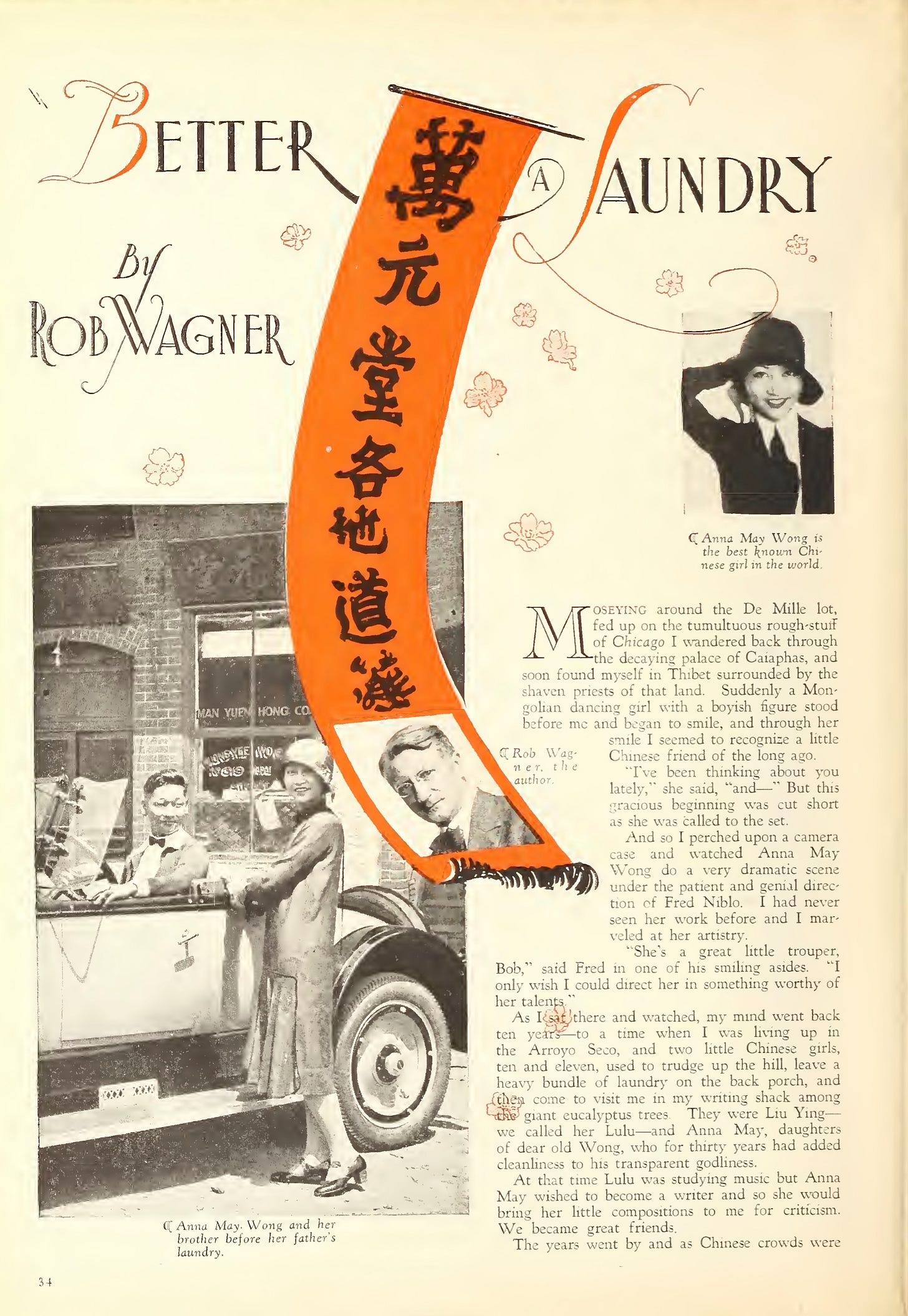

As the daughter of Chinese immigrants who has described herself as having been “brought up with an ear to two cultures,” Jennie Liu does a masterful job of weaving Anna May Wong’s story together with her protagonist’s imagined one. Anna May’s recent surge in popularity has spawned a number of novels that either include her as a character or characters inspired by her. The Red Car to Hollywood is my favorite of the ones I’ve read so far. You can tell the amount of care Jennie has put into the research—in fact, that’s how we first connected. Jennie emailed me around the time we were both finishing up first drafts of our manuscripts and we traded a few newspaper clippings.

Her book was such a joy to read because unlike nonfiction, where one has to stay firmly tied to the facts, it imagines the world that Ruby and Anna May inhabited in a way that is incredibly satisfying. For example, I’ve always known that Anna May’s career caused strife at home. Her parents didn’t always agree with her acting but they were willing to look the other way when she brought home fat paychecks. But there are no recorded conversations Anna May might have had with her parents (other than episodes she recounted in interviews). In Red Car, we actually get to see and hear how her family might have responded to things like seeing her stripped down to that scandalous Mongol slave’s costume for The Thief of Bagdad. With all this in mind, Jennie and I got together to discuss where the idea for her book came from and how she set about writing it.

How did the idea for The Red Car to Hollywood come to you? When did you first become interested in Anna May Wong?

I first read about Anna May Wong back when Lisa See’s nonfiction book On Gold Mountain was released. She came back into my consciousness with PBS’s documentary Asian Americans in the spring of 2020. I was looking for story ideas at that moment and racism was at the forefront of my mind because George Floyd had just been murdered and the coronavirus dog-whistle to anti-Asian hate was being ramped up by the president. Anna May was such an interesting person, and her endurance in the face of racism was so heartening that I wanted to spread her story.

One of the things I loved about your book is that it imagines what aspects of everyday life must have been like for your protagonist Ruby Chan as well as for Anna May Wong and others in the Chinese American community of Los Angeles in 1924. For example, we see the way Ruby gets exoticized when her employer insists that she wear a cheongsam, instead of the standard uniform, in her role as an elevator operator at a downtown department store. We also get to see how Anna May’s family reacts to her film career in various scenes. In one instance, Ruby overhears an argument between Anna May and her father, who has just attended the premiere of The Thief of Bagdad and isn’t happy about how much skin she bared in it.

Because it’s a novel, you have the creative license to explore so much more of Anna May’s life—you can fill in some of the blanks about things that likely happened but we don’t know for sure—which I truly enjoyed. It was also fun to see her brother, James Wong, become a full-fledged character. To be honest, your book is the first time I’ve read any fiction that captures Anna May in such a realistic way. I promise there’s a question here! What I’m curious about is how you constructed the narrative and why you decided to make Anna May a supporting character rather than the main protagonist?

Because I write for young adults, I was certainly interested in Anna May’s life as a teenager when her career really began to take off, but apparently she was involved in romantic entanglements with older men in her industry. I felt if I were to write about a teenage Anna May, those relationships would have to be a significant part of the story, and I just really did not want to spend time exploring that. And it was a little intimidating to think about building an entire novel around a true historical figure, especially given my limited ability to research at the time.

I began to think about other ways I could frame a story. My read of the biographies available at the time seemed to present Anna May’s life with somewhat of a sorrowful trajectory. But Anna May was audacious, throughout her life, but especially in her youth. Despite her family’s disapproval and the systemic racism of Hollywood, she always expressed pride in her heritage in interviews and through style choices. Surely the other Chinese American girls knew about her and looked up to her. I was curious about what these other Chinese American girls were like in the 1920s, so I decided to have an “ordinary” girl as the main character who deals with the similar issues of exoticism, racism, and family pressure.

The book is clearly grounded in the facts surrounding Anna May Wong’s life, which I appreciated. What did your research process look like? I’m especially impressed with how you were able to describe 1920s Los Angeles in such detail.

Oh, thank you! That means so much coming from a historian and a Californian.

The pandemic was full on when I began working on the story. Research was difficult because libraries and historical societies were shuttered. I could buy books online from used book sellers. Information about silent movie era Hollywood, LA history, and the history of Chinese in America was easily found, and I also dug up a couple of excellent books about the Old Chinatown of LA and a few that had bits about the early generations of Chinese American girls and the connection of Chinatown to Hollywood.

Interviews and profiles of Anna May from movie magazines, which I found on digital archives (and occasionally on fan pages), put her voice in my ear and gave me some details of her daily life. Some of the articles were published a few years later than the time of my story, but I found them to be so telling in how she projected herself to the public. Flipping through the stories and the ads in those magazines put me in the mindset of the young people and women of the time. I also read quite a number of novels that were actually written around my time period, ones that centered around working-class people, and classic LA novels. I had 1910 and 1930 illustrated maps with all the landmarks of the city, historical streetcar maps, and some basic maps of Old Chinatown that helped me move the characters around the city. I really studied digitally archived photos of the different parts of LA in the twenties.

And of course, I watched silent movies on YouTube! The ones of Anna May for sure, but also some that showed LA in the backdrop.

For those who are not familiar with Los Angeles history, can you tell us what the Red Cars were and why you chose that reference for your title?

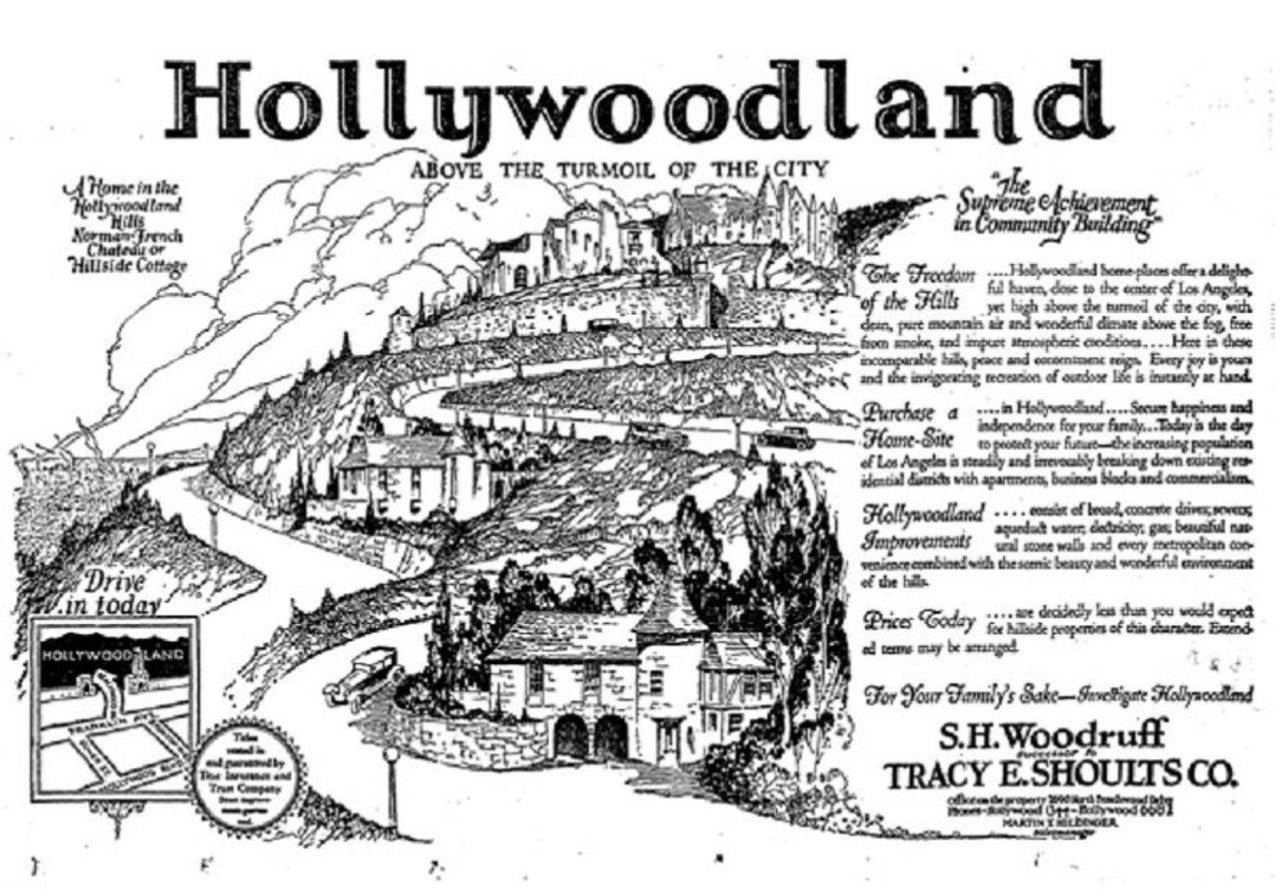

The Pacific Electric railway system in LA and Southern California was the largest interurban system of electric train cars in the early 20th Century. It provided efficient and inexpensive transportation to the surrounding cities in the Los Angeles basin. The system was known as the Red Cars because the train cars were painted red, whereas the Yellow Cars of the Los Angeles Railway operated within the city. For a while, my working title was Red Car to Chinatown because I wanted the focus to be on Chinatown. But once I understood the transit system better and finally got hold of an early map of the lines, I saw that the closest Red Car stop near Chinatown wasn’t as near as I hoped.

But it turned out to be a good title. In 1924, Hollywood was still very young, a municipality connected by a Red Car. A pivotal scene of the story takes place in Hollywoodland, the brand-spanking-new housing development under the iconic Hollywood sign, also on Hollywood Red Line. The development was racially exclusive. Newspaper ads urged people to “protect your family by procuring a homeplace in the Hills of Hollywoodland—secured by fixed and natural restrictions against the inroads of metropolitanism.” Fixed restrictions allude to deed restrictions that legally allowed developers to prevent non-Caucasians from buying in. I didn’t know all this when I decided to have a scene at this location. After I learned about it, the housing development took a larger part.

A big part of the book centers on interracial love and the laws and cultural expectations guarding young Chinese American women, who were a statistical anomaly in 1920s Los Angeles. In your Author’s Note, you write that the 1920 Census counted just 29 girls between the ages of 14 and 18, out of 2,951 Chinese residents (which would have included Anna May).

Why was it important to you to highlight these regulations, such as the ban on interracial marriage, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and the Expatriation Act (which mandated that American women who married a non-citizen would automatically lose their citizenship)? How do you feel these governmental intrusions added to the cultural pressures that young women like Ruby and Anna May had to contend with, both from their Chinese parents and the largely white American public?

The 1920s was a big leap in social change for American women, but for girls like Ruby and Anna May, pressure to be ‘good’ and not draw attention came not only from family and traditional Chinese culture, but also from pervasive racism (those laws!) which caused immigrant communities to further insulate themselves and perhaps double down on keeping their kids close. One would like to be able to look back at history and see that we’ve come a long way since such heinous legislations, but sadly, terrifyingly, regulations that perpetuate fear and oppression of certain groups are still popping up to this day.

The Red Car to Hollywood is geared toward YA readers but it’s a great read for people of all ages. What do you hope readers take away from it?

One defining hallmark of a YA novel is that the story ends with a sense of hope. Well, we sure need that now!

The Red Car to Hollywood by Jennie Liu is available for purchase here or at your local bookstore. You can follow Jennie on Instagram and her website.

I loved this. Thank you both.

Such a rich conversation! Congratulations Jennie! Thanks for adding to the literary canon on Asian American Hollywood!!!!