The Double-Edged Sword of Being Other

or how to survive type-casting

Researching the life of Anna May Wong and reading through articles, reviews, and interviews published nearly a hundred years ago, I frequently stumble upon turns of phrase and blithe assertions of fact that would never be uttered out loud today, let alone immortalized in print (although then again…). An occupational hazard, I suppose. The headlines alone are a case study in racial cliches not to use in 2021:

A Chinese Puzzle

Between Two Worlds

Velly Muchee Lonely

The China Doll

Where East Meets West

Anna May Wong Sorry She Cannot Be Kissed

A Lone Lotus

Coming across off-color comments in the pages of movie magazines and newspapers from the 1920s and 30s is not really a surprise. Still, seeing someone refer to a Black person as a “darkey” or dubbing a theatre’s double feature program as “Slap the Jap Week” isn’t any less horrendous or repulsive because it was done 80+ years ago. But on some level it’s expected. And somehow it’s easier to forgive generations of people who are long dead and gone. “It was a different time,” some might say.

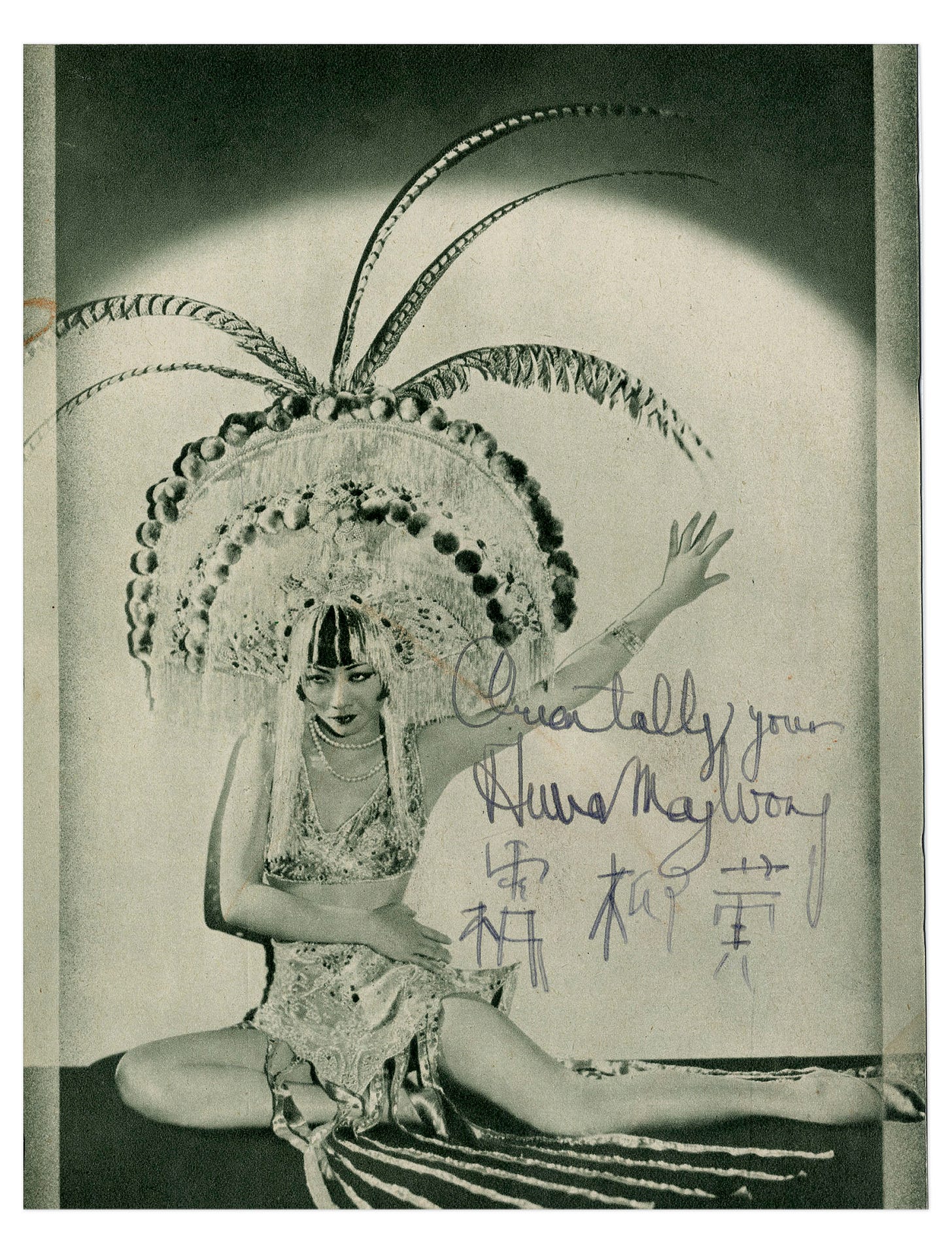

What has surprised me more are the ideas and thoughts expressed in recent memory, as if their proximity to the present moment’s racial reckoning renders them impossible to forgive. This is the culprit I’m thinking of: A few months ago I came across a piece in the New York Review of Books (a “left-leaning intellectual magazine”) by Robert Gottlieb on two books about Anna May Wong that were released in 2005 for the 100th anniversary of her birth—Anna May Wong: From Laundryman’s Daughter to Hollywood Legend by Graham Russell Gao Hodges and Perpetually Cool: The Many Lives of Anna May Wong by Anthony B. Chan. The review, published 16 years ago, was titled “Orientally Yours.”

Now, before anyone jumps to conclusions, that phrase was actually coined by AMW. It’s how she often signed her name on headshots and in autograph books. (You might have noticed when you signed up for this letter that I also signed my welcome email with this same expression.) “Orientally Yours” is not just a catchphrase that allowed AMW to foreground one of her most obvious qualities—she was Asian, unlike 99% of the actresses in Hollywood—but it is also a line to subtly hint that there is more going on than meets the eye. I’m aware that some might call this pandering to white America’s fetish of the exotic, but for those who can read between the lines, AMW is winking at us. She wants us to know that she knows she’s playing a part, the “Oriental flapper,” “The World’s Most Beautiful Chinese Girl,” and by doing so, she’s slyly challenging white America at its own game.

AMW had a wonderful, incredibly subversive sense of humor (she was Cantonese, after all), which did not come through in her film roles. I’m convinced that “Orientally Yours” was as absurd and laughable a salutation in the 1930s as it is today, which is what makes it work. It’s a gimmick, but it’s also provocative, even inflammatory. This, too, was lost on Gottlieb, as he remarks that “Oriental” is “a politically incorrect appellation these days, but Wong didn’t know it back then.” He seems to congratulate himself for unearthing a contradiction in “PC culture.”

Gottlieb goes on to summarize the racism experienced by AMW in childhood and in her film career as described by Hodges and Chan in their books. He notes that AMW was determined to escape the misery of laundry work, to ask more of her life, and that she would become successful in this pursuit because “she was also becoming exceptionally beautiful.” He continues:

It had taken determination, intelligence, and luck for Wong to reach the level of success she had achieved. The luck lay in her beauty and her ethnicity—and there is the issue on which both Hodges and Chan get it wrong. They believe that her skin color held her back, whereas it was clearly her skin color that made her unique in the Hollywood of her early years and gave her the place she occupied there.

It is true that AMW’s inescapable Chinese-ness, no matter how American she might have been at her core, helped her stand out from the crowd. Indeed, it’s all anyone ever seemed to want to talk about when her name circulated in the press.

In The Drama of Celebrity, scholar Sharon Marcus explains that stars and their public each helped to establish and reinforce “the parameters of a particular celebrity’s type, their consistently present, relatively distinctive, and readily identifiable traits.” In fact, “the more distinctive the star, the more readily they become a type.” Based on looks alone (and the bias they triggered), AMW never had a chance at becoming the girl next door type, the bombshell, or the femme fatale (she came close to this last one, but in the end, she was always the one to die, not her lover). If I were to spell out AMW’s type in words appropriate to her time, I’d wager she would be labeled “the tragic Oriental.”

So to say that AMW’s ethnicity did not hold her back in any way, that it was the source of her success, the reason she ever found a place in the Hollywood firmament, is blindingly ignorant. What really takes the cake, though, are the last two paragraphs of Gottlieb’s review, his coup de grace:

[These biographies’] greatest grievance lies in MGM’s failure to give Wong the female lead in the 1937 epic film of The Good Earth, a novel that had topped best-seller lists for two years, won a Pulitzer Prize, and led to Pearl Buck’s being awarded the Nobel Prize for literature, a major embarrassment. The loss of this role had embittered Wong. But the heroine of The Good Earth is a young peasant woman, leading a simple, arduous life: “Do not come into the room until I call,” she says, as she prepares to give birth. “Only bring me a newly peeled reed and slit it, that I may cut the child’s life from mine.” What has this O-Lan to do with the exotic Daughter of the Dragon? In Hollywood, type is type, and stars are stars. For a major role in a major production, no studio would have cast a fading B-film actress, whatever her ethnicity; better to go with an admired European artiste, Luise Rainer, who had just won an Oscar (for The Great Ziegfeld). Although she won a second one for The Good Earth, Rainer is ludicrous as O-Lan. Indeed, the whole movie is ridiculous. But that doesn’t mean that Anna May Wong, through some kind of premature affirmative action, had a right to the role.

Whatever the ugliness of bigotry in America in her time—pre-Gong Li, Maggie Cheung, Zhang Ziyi—and however her skin color may have limited her chances to become a real leading lady, Anna May Wong’s far from negligible career came about because she was an Asian-American woman. That’s what made her interesting to Hollywood, and to canonize her as an underrated artist and a victim of racism is to do her a disservice. Today, ironically, Anna May memorabilia is commanding higher prices on eBay than that of her old colleague Dietrich. But then, no one has ever claimed that Dietrich was underrated, or a victim.

Where to even begin? I was so angry the first time I read this I must have been seeing red. I scrolled to the author’s credentials: “Robert Gottlieb has been the Editor in Chief of Simon & Schuster and of Knopf, and the Editor of The New Yorker.” Of course he was. All the signs of white male privilege in the literary world, I should have known. I checked to see if he was still alive (the review was published in 2005) and swiftly pronounced him dead (If not literally so, at least in cultural relevance. Robert Gottlieb, apparently, is still very much alive at 90 years old and published his personal memoirs in 2016). I methodically bookmarked the link and then x’d out of the tab, thinking, I’ll deal with you later.

And here we are. So let me tell you what’s so wrong with everything he attempts to argue. First, he implies that AMW was not a fit for the role.

But the heroine of The Good Earth is a young peasant woman, leading a simple, arduous life . . . What has this O-Lan to do with the exotic Daughter of the Dragon?

AMW couldn’t possibly have known what it’s like to lead “a simple, arduous life.” She only grew up in a working class immigrant family and from an early age helped run the laundry business that kept food on the table. Since she’d once played the scheming, vengeful daughter of Fu Manchu in Paramount’s Daughter of the Dragon, she’d never be convincing in a different kind of role. Type is type. God forbid actors demonstrate artistic range.

For a major role in a major production, no studio would have cast a fading B-film actress, whatever her ethnicity

Well, I wonder why AMW became a so-called “fading B-film actress.” Could it have been because the studios wouldn’t cast her in lead roles or let her white male counterparts kiss her on screen?

better to go with an admired European artiste, Luise Rainer

OK, so AMW was not admired and she was no artiste. Or could it be that Rainer was seen as superior due to her Austrian pedigree? (In fact, Rainer was German, but these were the years leading up to WWII and there was already a sense that it was not a good thing to be German, so PR conveniently flubbed her nationality.)

Rainer is ludicrous as O-Lan. Indeed, the whole movie is ridiculous. But that doesn’t mean that Anna May Wong, through some kind of premature affirmative action, had a right to the role.

Gottlieb won’t say that Rainer’s performance is good or even worthy of the Oscar it won her. Instead, he virtue-signals his agreement of how ridiculous The Good Earth is because he, of course, is not racist. And yet, he dares to suggest that giving a Chinese role in an American film to a Chinese American actress is somehow affirmative action? If not Anna May Wong, then who, pray tell?

Whatever the ugliness of bigotry in America in her time—pre-Gong Li, Maggie Cheung, Zhang Ziyi—and however her skin color may have limited her chances to become a real leading lady, Anna May Wong’s far from negligible career came about because she was an Asian-American woman.

According to Gottlieb, talent has nothing to do with AMW’s “far from negligible career.” Last time I checked, by the way, all those actresses he mentions were leading ladies in primarily Chinese-made films, and as much as I love watching Maggie Cheung descend into a basement noodle shop in a sumptuous, 60s-inspired cheongsam, she is not an Asian American actress.

Comparing AMW to any of these women is like comparing AMW to the Empress Dowager Cixi (which actually happened in one of my publisher meetings when I was trying to sell my book). They have nothing in common except that they are ethnically Chinese and biologically female.

Today, ironically, Anna May memorabilia is commanding higher prices on eBay than that of her old colleague Dietrich. But then, no one has ever claimed that Dietrich was underrated, or a victim.

Right, because Marlene Dietrich wasn’t underrated. Her name never slipped out of public consciousness. Also, no one ever argued that the sale of Van Gogh’s paintings for millions of dollars only after his death was some great consolation to the creative frustration and rejection he experienced in life. Quite the contrary, it is held up as a rueful example of the vagaries of taste and public acclaim. Check mate.

There is one lone point on which I agree with Gottlieb. Anna May Wong was not a victim. She was a survivor. As such, I refuse to characterize her life as tragic. Tragedy and victim are labels others have always imposed on her.

Sharon Marcus, the scholar on celebrity, reminds us that there has always been a transgressive quality to star power: “The public attachment to shameless nonconformity points to a craving for what critic Roland Barthes called the ‘distance without which there can be no human society.’ Celebrities, by boldly making their shows of defiance public, do more than simply display unconventionality. They model an emotional attitude of indifference to nonconformity’s potential consequences.”

Anna May Wong’s mere existence was defiance itself. That doesn’t mean it was easy or inevitable. She showed up again and again, insisted on making her presence known as a Chinese American woman in a world that denied the existence of such a thing, even when it came at great personal cost.

In her last film, Portrait in Black (1960), a vehicle meant to reboot Lana Turner’s career in middle age, AMW plays Tawny, the housemaid. To see her relegated to this role at the end of her career is painful. But being Anna May Wong, she finds a way to imbue Tawny with an elegance and intelligence the script likely never called for. She practically smirks as she delivers an incriminating letter to her mistress near the end of the film, as if to tell us she has known all along what we as movie-goers are only just now beginning to realize.