The Way of the Warrior

Bruce Lee, Kung Fu & holding out for a hero

Last night I finished watching Season 3 of Warrior, the Bruce Lee-inspired show set in San Francisco’s Chinatown circa 1878. The series follows the story of Ah Sahm, a mixed-race martial artist who sails from Foshan, China in search of his sister, Xiaojing, who has fled to California after escaping her abusive warlord husband, a man she was forced to marry in order to spare her brother’s life.

When Ah Sahm, played by Andrew Koji, finally lands in America, he has his “you’re not in Kansas anymore” moment. Passing through immigration he sees how his fellow Chinese are ridiculed and assaulted. A white immigration officer slaps him after he stands up for one of his countrymen. And though his impulse is to hold his head high and fight back—in a clear homage to Bruce Lee, Ah Sahm tastes his own blood and then proceeds to whoop the asses of three officers—it doesn’t change his new, searing awareness that the Chinese occupy the bottom tier of society in this foreign land. He’s soon conscripted into one of Chinatown’s tongs, the Hop Wei, and not long after discovers that his sister has remade herself on this side of the Pacific as the strong-willed wife of Long Zii, leader of a powerful rival tong and the Hop Wei’s mortal enemy.

You couldn’t ask for a better setup for a pulpy, wisecracking kung fu drama that’s rooted in a deep cut from American history—a period of racial tension in the West between working class Chinese and Irish in the run up to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882—but self-aware enough to have some fun with it. Of all the Chinese dialects, I’ve always heard that Cantonese has the most prolific and effective profanity, a lexicon for insults that rises to the level of poetry. So listening to the sharp-tongued repartee in Warrior, which is delivered in fluent English for the benefit of viewers, is probably the closest I’ll ever get to enjoying the braggadocio of Cantonese.

The producers behind Warrior, Justin Lin (best known for Better Luck Tomorrow and the Fast & Furious franchise) and Shannon Lee (daughter of Bruce Lee and head of his estate), are well aware of the shoulders the show stands upon. The near-mythical origins of Warrior can be traced back to an 8-page treatment that Bruce Lee wrote himself. According to Lee’s biographer, Matthew Polly, “The story was set in the Old American West. Ah Sahm was a Chinese kung fu master who traveled to America to liberate Chinese workers being exploited by the tongs. In each episode Ah Sahm helped the weak and oppressed as he journeyed across the Old West.”

Although Lee’s plans for The Warrior, as it was then called, were mentioned in press interviews, the show was never produced. And then, in July of 1973, just as the Chinese American action hero was poised to hit peak popularity in the U.S. with the release of Enter the Dragon, Lee succumbed to a cerebral edema and died. Thus, the Warrior television series we have today, as one critic put it, has been in development for nearly half a century. Indeed, 2023 marks the 50th anniversary of Lee’s death.

But the story doesn’t end there. Another television series ultimately usurped the place that The Warrior might have held in 1970s pop culture. It was called Kung Fu, a Chinese word that few Americans had ever heard of before, and it premiered on ABC in 1972 with actor David Carradine starring as Kwai Chang Caine, a mixed-race Shaolin monk who uses his martial arts skills only as a last resort—though this turns out to be fairly often in the rough and tumble terrain of the Wild West. Some have argued that Kung Fu is a clear rip-off of Bruce Lee’s treatment, only with a white actor in yellowface installed in the lead role instead of an Asian actor. This was the version of events I gleaned from ESPN’s documentary on Lee, Be Water, which I noted in one of my previous dispatches.

The truth, it seems, is a little murkier. The script that later became Kung Fu was first conceived of by a Jewish writer from Brooklyn named Ed Spielman. As a teenager, Spielman had been captivated by Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, which touched off his obsession for all things Asian—including studying Chinese and practicing karate and kung fu. In 1967, while he was working as a comedy writer, Spielman sat down and wrote his first movie treatment about a Japanese samurai who travels to the Shaolin Temple in China to learn kung fu. Once he shared the treatment with his writing partner, Howard Friedlander, the story changed to a Western and the Shaolin apprentice, now named Kwai Chang Caine, was recast as the orphaned son of a white American father and a Chinese mother. “That Caine character is me in a way,” Ed Spielman explained. “He was always Eurasian; he always didn’t fit in.”

The treatment was shopped around as The Way of the Tiger, The Sign of the Dragon and an executive at Warner Bros. asked Spielman and Friedlander to write a full screenplay, which they submitted in the spring of 1970. For a brief moment, the film project looked like it was on its way to being greenlit as the first Hollywood vehicle designed to break Bruce Lee out as a full-fledged action hero. (Up until this time, Lee was primarily known in the U.S. for his supporting role as Kato, the crime-fighting chauffeur and sidekick on The Green Hornet, which aired on television from 1966 to 1967.) But once new studio heads arrived at Warners to clean house, it was decided that “the public would not be willing to accept a Chinese hero.” And just like that, the whole thing was canceled.

Bruce Lee moved onto other projects, but it’s unclear whether he drafted his treatment for The Warrior, which is undated, prior to reading Spielman’s script, or if, after auditioning for The Way of the Tiger and watching Warners quash it, Lee was subsequently inspired to write his own treatment to take elsewhere. We’ll probably never know the answer. And to some extent it doesn’t matter. Because Hollywood always betrays its own bigotry in the end.

A year later, Spielman’s screenplay was revived and sold as a made-for-TV movie, and then developed into Kung Fu. Bruce Lee was trotted out again for the role of Kwai Chang Caine when he returned to Los Angeles from filming The Big Boss in Thailand. Lee wasn’t messing around this time and made it clear he wanted the part. He showed up to Tom Kuhn’s office, the head of Warner Bros. TV division, and kicked the door shut. From his gym bag he pulled out nunchucks and began whirling them through the air, nearly missing Kuhn’s head. By the end of the meeting, Kuhn was impressed not only by Lee’s physical prowess, but also by his charismatic personality. As Matthew Polly writes, “On first blush, Bruce seemed perfect for the part. After all, he was the only actor in Hollywood who was also a Eurasian kung fu master.”

Here’s where history repeats itself. Despite his magnetic presence, Kuhn didn’t see Bruce Lee as a fit for Kung Fu. “I’ve never seen anything like that. But getting him the lead is still going to be a long shot,” Kuhn confessed, “He might be too authentic.”

Anna May Wong heard the same concern, though not in so many words, when she was passed over for leading lady roles time and again (which I document extensively in my book). Her thoughts on Hollywood’s obvious bias against Asian actors is enshrined in a letter she wrote to Carl Van Vechten: "I made a test at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios for the leading role in the 'Son Daughter,' the Chinese play David Belasco produced years ago with Lenore Ulrich. I guess I look too Chinese to play a Chinese, because I hear Colleen Moore is going to do it."

Kuhn’s real complaint against Lee was his accented English. “By the end of the half hour I really liked the guy, but frankly I had trouble understanding him,” he explained. “We’d have to loop the hell out of this guy for an American television audience to understand him. And you can do that with a movie, but you can’t do it on an every-week basis with a television show.”

With Bruce Lee crossed off the list, the production was free to test other actors, and after claiming they had auditioned “every Asian in Hollywood” including George Takei, they decided they would stick to white actors. Kwai Chang Caine was half-white after all. In came actor David Carradine, who was high as a kite and “bouncing off the walls” when he read for the part. Yet with some prodding by his agent, he was brought in again, this time dead sober, and clinched the role on his second try. “That was the last time I ever saw David Carradine straight,” Kuhn said.

Kung Fu was a huge hit and pop culture sensation. It became one of the most popular television shows of the 1970s, with as many as 28 million viewers tuning in each episode, and earned Carradine nominations at the Emmys and Golden Globes. His stoner persona somehow meshed perfectly with Caine’s stoic, mystical characterization and pacifist ethos.

The series also provided jobs for many working Asian American actors who were happy to take on supporting roles and background work. It was because of Kung Fu that industry veterans like Philip Ahn, Anna May’s childhood friend, and Keye Luke, most famous for playing Charlie Chan’s number one son, got one last hurrah in the limelight. Both played wizened Shaolin monks who appear to Caine in flashbacks from his training and act as spiritual guides akin to Obi-Wan Kenobi and Yoda, counseling the young mixed-race monk as he encounters racist whites, “murderous” Native Americans, and other perils on his quest to find his half-brother in the West.

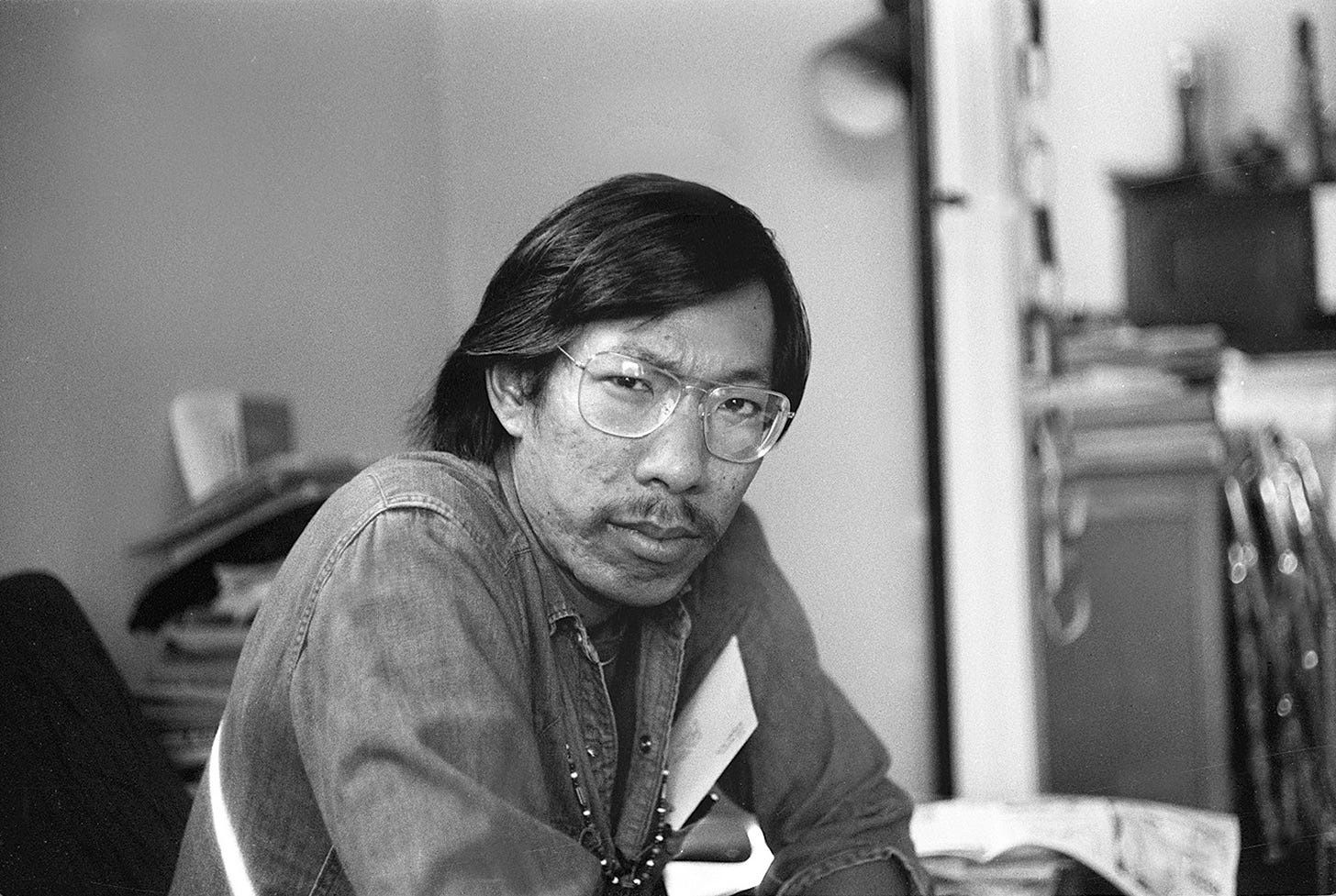

Despite the overwhelmingly positive response, the show still had its detractors. The fact that the star of Kung Fu was a white guy in makeup was hard to overlook. One of these voices was Frank Chin, a Chinese American playwright, pioneer of Asian American theater, and outspoken, sometimes inflammatory, critic of racism towards Asian Americans in popular culture. While researching my book on Anna May Wong, my interest was piqued when I came across a reference to Chin’s 1974 essay in the New York Times rebuking the success of Kung Fu. Except when I went to look it up in the NYT’s online archive, the article was strangely missing. All that remained was Ed Spielman’s thin-skinned response printed weeks later.

Thanks to the archivists at UC Santa Barbara, I was able to get a copy of Frank Chin’s broadside from his papers. His colorful diatribe, titled “‘Kung Fu’ Is Unfair to Chinese,” both amused me and had me nodding in recognition.

The progress that Asians of all yellows have made in the movies and on television is pitiful compared to the great strides in self-determination made by apes, dinosaurs, zombies, the Creature from the Black Lagoon and other rubber creations of Hollywood’s imagination.

In 40 years, apes went from a naked, hairy King Kong, gigantic with nitwit sex fantasies about little human women, to a talking chimpanzee leading his fellow apes in a battle to take over the planet. We’ve progressed from Fu Manchu, the male Dragon Lady of silent movies, to Charlie Chan and then to “Kung Fu” on TV.

We’ve made no progress at all. We’re still made out to be the likes of Keye Luke, Benson Fong, Philip Ahn and Victor Sen Yung at our worst and middling, and David Carradine—talking like he’s in a trance—at our best.

He makes a good point. Little had changed for Asian American representation by the 1970s, despite the short-lived triumph of Flower Drum Song a decade earlier. And David Carradine talked like he was in a trance because he was! High on the latest cocktail of drugs. When he wrote his autobiography in 1995, he titled it Endless Highway. And I don’t have to remind you how he died.

Salacious details about David Carradine aside, Chin has a deeper point here.

I believe the white need to see us yellows as passive, docile, timid, mystical aliens is deep enough for whites to lie down and think about out loud. “Kung Fu” explains why Chinese are so passive—they’re catatonic as the result of too many weird candlelight ceremonies and lots of bad writing.

Chin’s words echo something James Baldwin once said on television in 1963:

What white people have to do is try and find out in their own hearts why it was necessary to have a n— in the first place, because I’m not a n—. I’m a man, but if you think I’m a n—, it means you need it . . . If I’m not a n— and you invented him—you, the white people, invented him—then you’ve got to find out why.

The problem with Kung Fu, Chin suggests, is the fact that it presents a racialized image of Asian people as non threatening and submissive, an image that was invented and projected onto us to calm white supremacy’s deepest fears about the other.

The white image of yellows as too cultured, too philosophical, or too spiritless to pick up their shovels when a white man threatens them has obliterated not just the simple truth that Chinese miners were greedy enough to fight anybody for their gold, just like any other California miner, but also all the simple truths of our history—and our humanity.

Pick up an Asian-American magazine or newspaper. A debate is raging. The yellows who are against “Kung Fu” are advised to sit down and be grateful that Charlie Chan reruns and the “Kung Fu” series are making us sympathetic in the white man’s mind. And the majority, never having had a serious thought about our people mining for gold and building the transcontinental railroad, are so grateful to “Kung Fu” for making us likable that they look on its insults and inaccuracies as merely the price of acceptance in America.

But when we talk about “the price of acceptance” seven generations later, there’s something wrong with our minds. And the price of acceptance is a TV show! It’s crazy! But there it is in our papers and on our minds.

That’s a hell of a lot to pay—one more round with Charlie Chan. At this rate, I’ll be long dead before we catch up with the apes and the Creature from the Black Lagoon. We’ll be an extinct race before then. And a white man in yellow face will play somebody like me in another Charlie Chan movie.

Frank Chin is 83 years old and still kicking, as far as I can tell from his website. I don’t know whether he’s watched Warrior. But I’m dying to know what his take on it would be.

I’ve been a Warrior fangirl since I first started watching the series in 2020. The show hits all the sweet spots: it boasts a majority Asian cast with diverse roots, delves into a oft forgotten period of American history, delivers top-shelf fight sequences on the regular (though I could do without some of the gore), and refuses to victimize or villainize the various groups depicted and instead focuses on their shared human foibles (showrunner Jonathan Tropper maintains that there are no good guys or bad guys).

Warrior is the best damn kung fu show on television today—and maybe ever. I’ve watched a couple episodes of Kung Fu (it’s available for streaming) and the show hardly lives up to its name, the fight scenes are so rife with close-ups and crosscuts that it’s pretty obvious what they’re hiding. Of course, there’s no replacing Bruce Lee, but Andrew Koji makes a convincing effort, channeling Lee’s spirit in every frame.

I will admit a bit sheepishly that I’ve never sat through an entire Bruce Lee film (an oversight I promise to remedy as soon as possible), but Bruce Lee’s face, his look, his lightning-fast moves, his unmistakable, high-pitched screech have all been indelibly burned into my brain, whether from my older brother’s teenage obsession with him or simply by pop-culture osmosis. So even I know that when Andrew Koji wields a pair of nunchucks with effortless swagger or one-inch punches a man across the room, he does so with the intention of honoring the master who did it best.

In a country where Asian Americans rarely rise to the status of a household name (a recent survey showed that 44% of Americans could not name a single living Asian American), the thrill of Warrior is that it gives us a hero to root for.

A fan on the Warrior subreddit shared a clip from one of Andrew Koji’s fight scenes overlaid with the music from Bruce Lee’s 1971 film The Big Boss. In the comments below, another redditor sums up their reaction:

This is awesome and I swear this specific episode needs to be run on public television for 24 hour period after what the Asian American community has been through. This shit is more empowering than white IG influencers posting selfies with long ass masturbatory captions talking about how “we need to do better.”

Updates in Brief

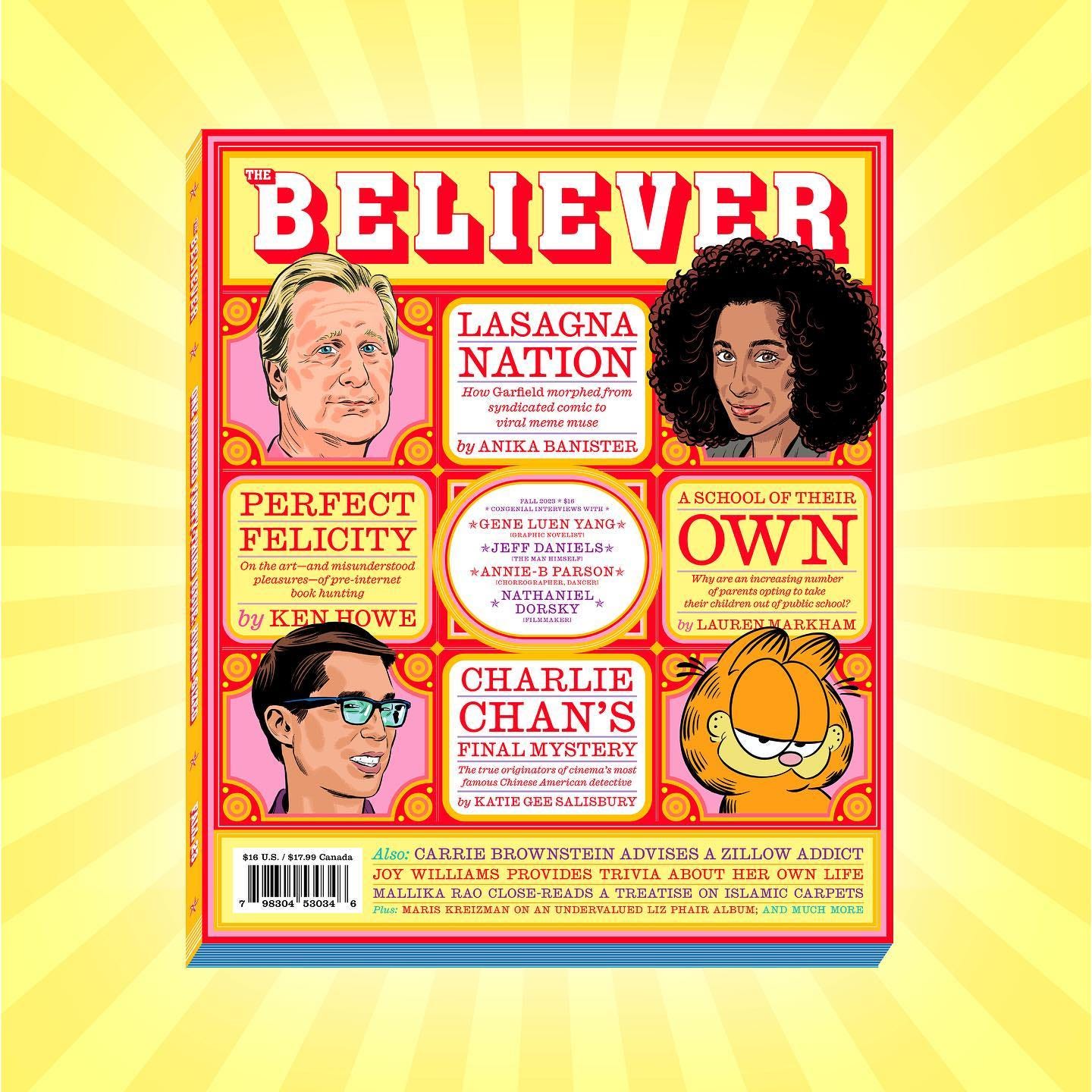

Speaking of Charlie Chan—说曹操,曹操就到—my first essay in The Believer is about the Asian actors who originally played the famous Chinese detective on screen, before white actors like Warner Oland and Sidney Toler later assumed the role in yellowface. Keep an eye out for “The Man Without a Face” in the fall 2023 issue of the magazine, which hits newsstands October 5. Or secure your copy by subscribing to The Believer here. p.s. I’m on the cover with Garfield!

Over the summer, I started a new Instagram channel devoted to Anna May Wong. Every few days I share some of my favorite photographs of AMW and the stories behind them, as well as updates on the book. So if you need a little more AMW in your life, follow along on IG at @annamaywongbook.

In other exciting news, advance readers copies for Not Your China Doll (or galleys, as we call them in the biz) arrived in the mail last week and I’m pretty stoked. The book has never looked more real. And even better, Goodreads is giving away copies to 12 lucky readers. Enter here by Oct. 4 to win one of them!

They always have it wrong about Bruce Lee. Hollywood is going another biopic by Ang Lee.

I hope they get it tight this time.

He was originally hated by Chinese and called White devil growing up. I am mixed Asian. And I experienced the same racism from Asians. My cousins who are mixed live terrible lives.

That is why he left Hong Kong. I taught a course on Bruce Lee cinema for years. I did my research.