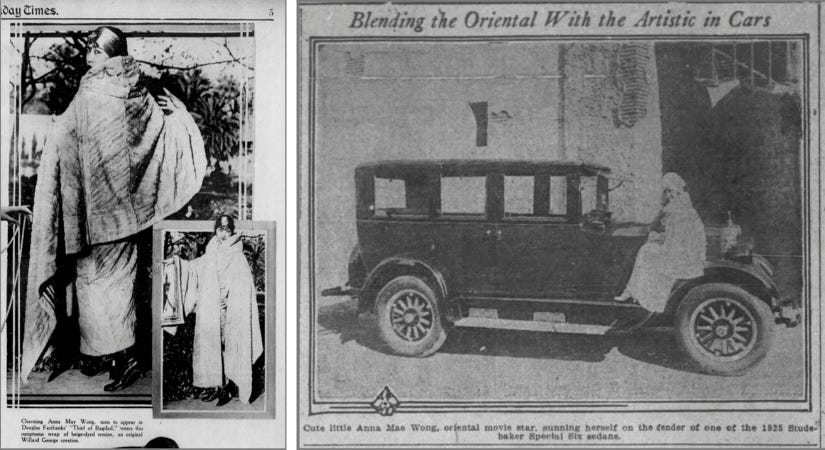

It started with a photograph, as it always does. Early in my research for Not Your China Doll, I came across a clipping of a twentysomething Anna May Wong posing with a car in front of “a well-known bit of Chinese architecture.” This was clearly a piece of “sponsored content” and not unusual for this moment in her career. She was still riding the wave of success from 1924’s The Thief of Bagdad and could often be found modeling furs and other products in local newspapers and magazines.

This, in fact, was not her first car modeling job. She’d previously had her picture taken with a 1925 Studebaker Special Six sedan on the set for Thief, decked out in her flapper finest. It makes me laugh, though, to see AMW using her celebrity power to sell cars. She was a notoriously bad driver in her youth (not because she was Asian!). Several articles mention her getting speeding tickets and crashing her car; by her own account, she once tried to outrun a motorcycle cop to a bridge. “I beat him all right,” she recalled, “but I missed the bridge.”

What set this particular photo apart was its backdrop—the Chinese architecture that isn’t really Chinese. It’s Japanese. (Which I had an inkling of because many years ago I took alllooksame.net’s architecture quiz and knew that Chinese roofs never have rounded eaves like the one you see on the tiled awning above the doorway.) But I wondered where such an elaborate mansion existed in early Hollywood. And was it still around? More likely it had gone the way of Pickfair, bought and demolished by new owners who had no respect for history.

I forgot about it for a few years, until one night when I was watching an episode of MTV’s reboot of The Hills. (Don’t judge!) One of the cast members was on a date at an Asian fusion restaurant, sitting outside on a terrace surrounded by a manicured garden with an incredible nighttime view of the city glimmering in the distance. The image stuck in my head. Eventually, I looked it up. The restaurant is named Yamashiro, which translates to “mountain palace” in Japanese, and nestled inside a hilltop mansion built by wealthy brothers more than a century ago. The pictures on the restaurant’s website were immediately familiar. This was the same mansion Anna May Wong had once posed in front of with a Marmon speedster.

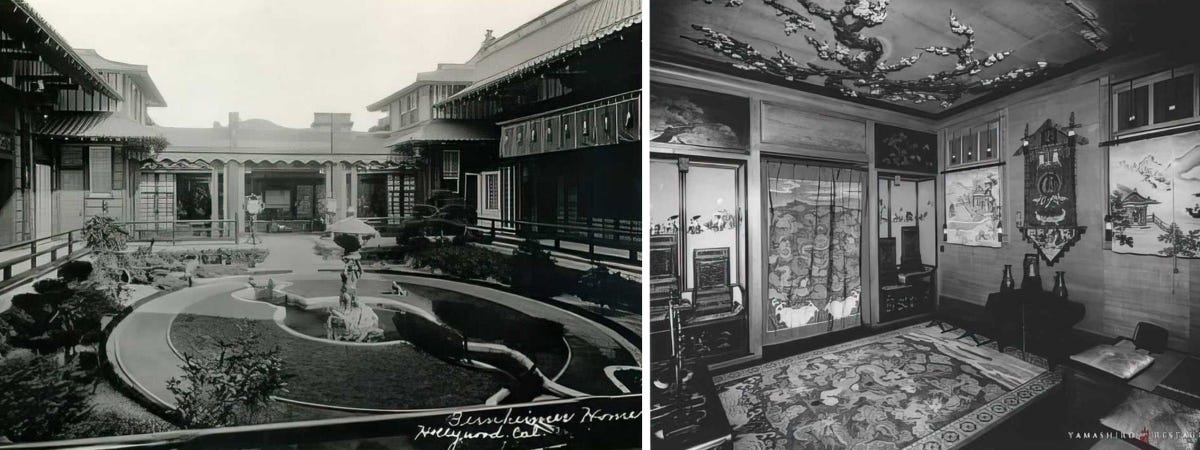

In its 110-year existence, Yamashiro has garnered many titles: fortress, castle, palace, mansion. Bachelor brothers Adolph and Eugene Bernheimer purchased several acres of land overlooking Hollywood Blvd. and built the home atop its peak in 1914 to enshrine their collection of Asian art. They had become rich through their business in the cotton trade and their frequent travels to East Asia had turned them into connoisseurs of silk and Asian antiquities. According to reports from the Los Angeles Times, the Bernheimers spared no expense in constructing and decorating their new home.

“Travelers who have toured through Nippon-land concede that there is nothing in native Japan to surpass the marvelous beauty of the Bernheimer villa, a replica of all desirable in a Japanese dwelling place. . . . The main entrance admits upon the reception room, small, almost austere, with carved oaken walls, relieved by the most wonderful tapestries of Japanese embroideries. Throughout the home these wonderful tapestries, hundreds and thousands of them, continue, the work of a thousand artists for a lifetime and more. With the finest silk they have been fashioned.”

The property also included a tea house, gardens landscaped with waterfalls and pools filled with koi fish, a private zoo of exotic birds and monkeys—“Black swans sail the pool in the Japanese gardens”—a miniature Japanese village complete with tiny canals and toy-sized boats, and a 600-year-old pagoda, purportedly the oldest structure in Los Angeles. All told, the house cost $250,000 to construct or $7.8 million in today’s money.

Interestingly, the same thirst for the exotic, demonstrated by the japonisme and chinoiserie then in vogue, that gave AMW some of her earliest on-screen opportunities, fueled the intrigue around this castle on the hill. And as in any neighborhood, people tend to talk about the biggest house on the block and its inhabitants. Whether true or not, the Los Angeles Times article on the house’s completion insinuated that the Bernheimers were eccentric recluses: “With the striking strangeness of it all, there comes a touch of sinister romance, for the hosts there are bachelors, and it is rumored that they have made a pact that no woman shall ever enter the place as an invited guest.”

Once World War I began, the brothers were subjected to more insidious suspicions because of their German Jewish background. “They were accused of smuggling in a German spy, of gun smuggling, of digging mysterious tunnels and of signaling German aircraft with the lights from their driveway,” the Los Angeles Times later reported. Indignant, the brothers called in an FBI agent and an Examiner reporter to dispel the rumors.

In 1924, Eugene died suddenly and his brother Adolph decided to sell the property in favor of developing a new Japanese villa in the Palisades on a bluff overlooking the ocean. The house soon passed into the hands of the socially scorned: motion picture people. As I write in the preface to my book, the “white Midwesterners of decidedly good stock” who first settled the farmland that became known as Hollywood were not so keen on this new class of actors and bohemian types. Even with the movie industry firmly entrenched in Los Angeles by 1925, country clubs and other high society circles still barred big name stars, directors, and producers from their membership rolls. The 400 Club, founded by actor Frank Elliott, aimed to change all that with the club’s new ownership of Yamashiro.

On the same day that the latest edition of the Southern California Blue Book, a society directory, went out in 1925, the 400 Club and its snubbed members held their inaugural meeting at the lavish mountain palace. “That was a profound and opportune gesture of deep significance—actually tantamount to five fingers spread perpendicularly from the end of a haughtily upturned nose,” Alma Whitaker, columnist for the Los Angeles Times, cheekily announced. Nearly all of Hollywood’s big players attended: Gloria Swanson, Harold Lloyd, Pola Negri, Charlie Chaplin, Alla Nazimova, Rudolph Valentino, Norma Shearer, Mae Murray, Conrad Nagel, Jesse L. Lasky, the Warner Brothers, Colleen Moore, Elinor Glyn, and the list goes on. “In the lovely patio, wisteria-vined, Art Hickman’s orchestra will play, Japanese girls will serve tea and hostesses, who are the elite of Cinemaland, will receive.”

Ironically, there doesn’t seem to have been any Asian guests invited to join the festivities. As far as I can tell, Anna May was never a member of the club, though she knew many of its constituents; even with 400 spots to fill, I suppose the club was still too exclusive to include a Chinese American actress. Meanwhile, Sessue Hayakawa, Hollywood’s Japanese heartthrob, had returned to Japan several years prior to escape growing anti-Japanese sentiment in the U.S. Though he’d previously filmed scenes in the house for the 1922 film The Vermilion Pencil.

The club, however, didn’t last long, as infighting soon led to its dissolution before the end of the decade. The property changed hands several times in the coming decades. When hard times hit in the Great Depression, the mansion was reportedly opened up to sightseers for 25 cents a pop. But as a very visible symbol of Japanese culture, the house fell victim to the whims of public opinion during World War II. With anti-Japanese fervor rampant, Yamashiro was vandalized and its former glory faded into the background. Conspiracies spread. Some theorized the hilltop manor acted as a signal tower for the Japanese in the war.

To allay these whispers, the mansion was covered up with boards to disguise its distinctive Japanese architecture. Occasionally it was rented out for events. At one point, it served as a boy’s military academy. Then after the war, the house was partitioned into separate apartments and rented out to various personalities, many of whom went on to make names for themselves in Hollywood like Richard Pryor, Jerry Dunphy, and Pernell Roberts.

In 1948, Thomas O. Glover bought the now dilapidated mansion with every intention of bulldozing it and developing a new hotel and apartments on the land. That was until he started peeling away the layers of plywood and paint that had covered up the home’s former opulence. He was surprised to find the delicate silk tapestries and teakwood carvings underneath and changed his mind about demolition. Slowly, Glover began to restore the house. He first opened its doors as a bar where patrons could sip their cocktails while enjoying the incredible vistas of Los Angeles. The concept was a hit, so he expanded to a full restaurant. Yamashiro has been thriving ever since.

Its connection to Hollywood has continued over the years, presenting a ready-made Japanese backdrop for films like Sayonara (1956) and Memoirs of a Geisha (2005). On my last trip to L.A. in August, I decided it was time to see Yamashiro for myself. I made an early dinner reservation before my event at Larry Edmunds Bookshop and we arrived just as the restaurant was opening. I snapped a few pictures while we still had the place to ourselves. The views really are as breathtaking as they say. Standing on top of the hill, I tried to imagine what it would have looked like when Anna May was up there, gazing down at the valley below. Today the Hollywood Hills are tightly stacked with multi-million dollar mansions, but back then, Yamashiro was one of the only homes up on the hills and could be seen for miles in every direction.

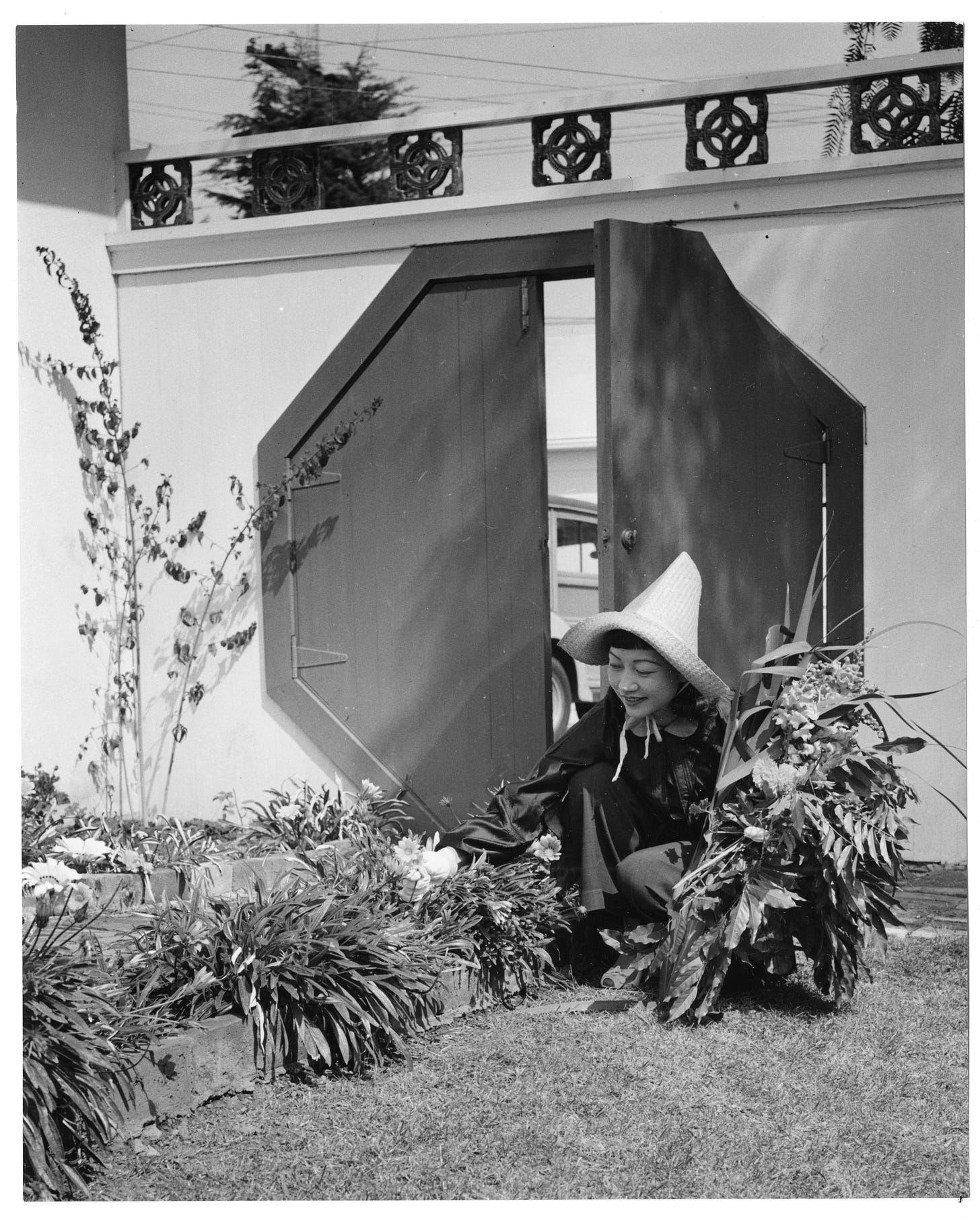

Now, back to that photo of AMW at Yamashiro. The Los Angeles Times article that accompanied it boasted that everything within the picture frame was Chinese: “A Chinese jade Marmon speedster, an attractive Chinese lass, with an exquisite home of Chinese architecture as a setting, and one has as pretty a picture as could be imagined.” The statement was a bit of a stretch, to be sure. But the article goes on to explain, “Anna May Wong, Chinese film star, the girl in the picture, says she chose the former luxurious Bernheimer mansion as her background because it is her dream of a palatial home and that the Chinese green Marmon is her idea of a motor luxury combined with dash and youthfulness.”

It’s especially charming to me that AMW selected this backdrop for herself and the car. The media were still trying to make sense of her. They didn’t understand what it meant to be Chinese American, and instead projected images of an exoticized China onto her. She was being cast into minor roles according to that vision, too. And yet, she herself longed to understand her own Chinese heritage. Being American born, she was divorced from the culture that other Americans immediately associated with her. What did she actually know about being Chinese—aside from growing up in the Wong household? In truth, she’d only heard stories about China from her father. In films, she was merely playing at being Chinese.

In his memoir, Japanese actor Kamayama Sojin recalled how Anna May often carried a copy of Confucius’ Analects with her on set. This small detail speaks volumes. The young AMW yearned to understand where her family came from, to understand who she was—and, perhaps, whether the stereotypes Hollywood assigned to her were true or not. Even in a Japanese-inspired mansion built by American businessmen, she saw something of herself.

To me, this picture marks a beginning of sorts. “Second to Miss Wong’s ambition to be among the greatest actresses on the stage is her desire to own a beautiful home and a stunning Marmon speedster.” It’s the airing of a wish that would later come to fruition (the home, not the speedster—that’s pure advertising).

Anna May did eventually make a trip to China in 1936 and it changed her life. When she returned to Los Angeles, she finally put down roots and made her own dream come true. She bought a property in Santa Monica, remodeled the house to include modern elements of Chinese design, installed an eight-sided moongate like the ones she had seen in the walled gardens of Beijing, and christened her new residence Moongate. It may not have been a castle on a hill, but it was home. As for the green Marmon, better to let Anna May advertise cars than to drive them!

A Thank You to Subscribers, Old & New

We’re coming up on the fourth anniversary of Half-Caste Woman soon and to thank readers, I’m running a special subscription drive from now until next Sunday, September 22. Subscribe to Half-Caste Woman (if you’re already subscribed, you’re eligible!), follow @annamaywongbook on Instagram, and I’ll send you one of these nifty #StarringAnnaMayWong postcards I created using AI art.

Amazing work. The story is so big. Keep it coming, Katie!

Wow what a structure....great writing... I so enjoy