For someone who was once named “the best-dressed woman in the world,” it’s surprising to learn that so little of Anna May Wong’s wardrobe remains with us today. This is partly due to Anna May’s own charitable acts. During WWII she auctioned off much of her personal closet to raise money for United China Relief. Many of these pieces are likely still tucked away in private collections, but some have started to come out of the woodwork, such as the two dresses author Lisa See donated to the Chinese American Museum in Los Angeles last year.

One garment in particular has become a symbolic stand-in for the Chinese American film star: the black, form-fitting dress designed by Travis Banton, unmistakably emblazoned with a golden dragon on the front and back. The dress, which AMW wore in Limehouse Blues (1934), is perhaps the only costume from her films that is still extant. In 1956, she gifted it to the Brooklyn Museum and it was later consolidated into The Met’s Costume Institute (underscoring the importance of public archives). It’s also a prime example of the limitations Hollywood placed on AMW as an Orientalized, ornamentalized persona. While the design is one of Banton’s most spectacular creations for Anna May, showing off her lithesome figure, it also renders her the literal embodiment of the dragon lady—a stereotype that many of her films regrettably cemented in public discourse.

Monstrous Beauty: A Feminist Revision of Chinoiserie, a new exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, has put the dragon dress back on display (which was last seen in China: Through the Looking Glass in 2015). This provocative show examines the West’s obsession with porcelain and its fantasies of the Orient through material objects, and how the desires imprinted on these luxury items were in turn imprinted onto Asian women, subjecting them to a kind of objecthood. Cue the pervasive China doll stereotype.

The brilliant mind behind the exhibition is Iris Moon, Associate Curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts at The Met. She is the author of several books, including Melancholy Wedgwood, an unconventional biography of Josiah Wedgwood, a ceramics entrepreneur in eighteenth-century England. In addition to curatorial work, she also teaches in New York.

In June, Iris very kindly escorted Anna Wong and I through the exhibition while we were visiting The Met for a screening of The Toll of the Sea. Weeks later, I’m still thinking about that experience. In the interview that follows, Iris shares some of her intentions behind the exhibition and the questions she hopes it poses for visitors.

As the exhibition statement explains, Monstrous Beauty “radically reimagines the story of European porcelain through a feminist lens. When porcelain arrived in early modern Europe from China, it led to the rise of chinoiserie, a decorative style that encompassed Europe’s fantasies of the East and fixations on the exotic, along with new ideas about women, sexuality, and race.”

The connection the show draws between porcelain and Asian female bodies certainly hit a nerve for me, but I realize it may not be an immediate association for those not immersed in discussions of Orientalism or the casual, everyday objectification of Asian women.

What inspired you to curate this exhibition? Did you have a guiding principle or line of inquiry that directed your thinking and influenced how you pulled the various pieces together?

As a curator of ceramics and glass in the European Sculpture and Decorative Arts department, I was curious why there were so many chinoiserie objects. This is an exotic, historical style invented by Europeans that encompassed both luxury objects imported from Asia and the European imitations made after them. Think porcelain cups covered in dragons and blossoms, fantasy pagodas and rock gardens, or furniture decorated with fretwork. What inspired me to curate this exhibition were a series of questions that emerged in looking at these objects in our department: What coded these works as foreign and strange? What made Europeans so obsessed with this fantasy of the faraway and strange? And how did a style applied to objects inadvertently become used to describe people?

When Anna Wong and I visited the Met last month, we had the incredible honor of taking a private tour of the exhibition with you. As we walked through the gallery, you shared insights into the objects and artwork on display as well as your intentions behind the curation. You also mentioned your determination to include Anna May Wong in the show, which was not an obvious choice to some. Why did you feel strongly about AMW’s inclusion?

Anna May Wong was described by film critics as the “living embodiment of chinoiserie.” She formed an important part of the exhibition narrative by showing how this style applied to inanimate objects was applied to individual people. On the one hand, Anna May Wong used the glamor, mystery, and beauty associated with chinoiserie over many centuries as a vehicle for her own film career. On the other hand, she became trapped by the stereotypes and fantasies that the West had constructed around the Asian woman, as an “exotic” figure who had to repeatedly play out the one-dimensional fantasies that were not of her own making.

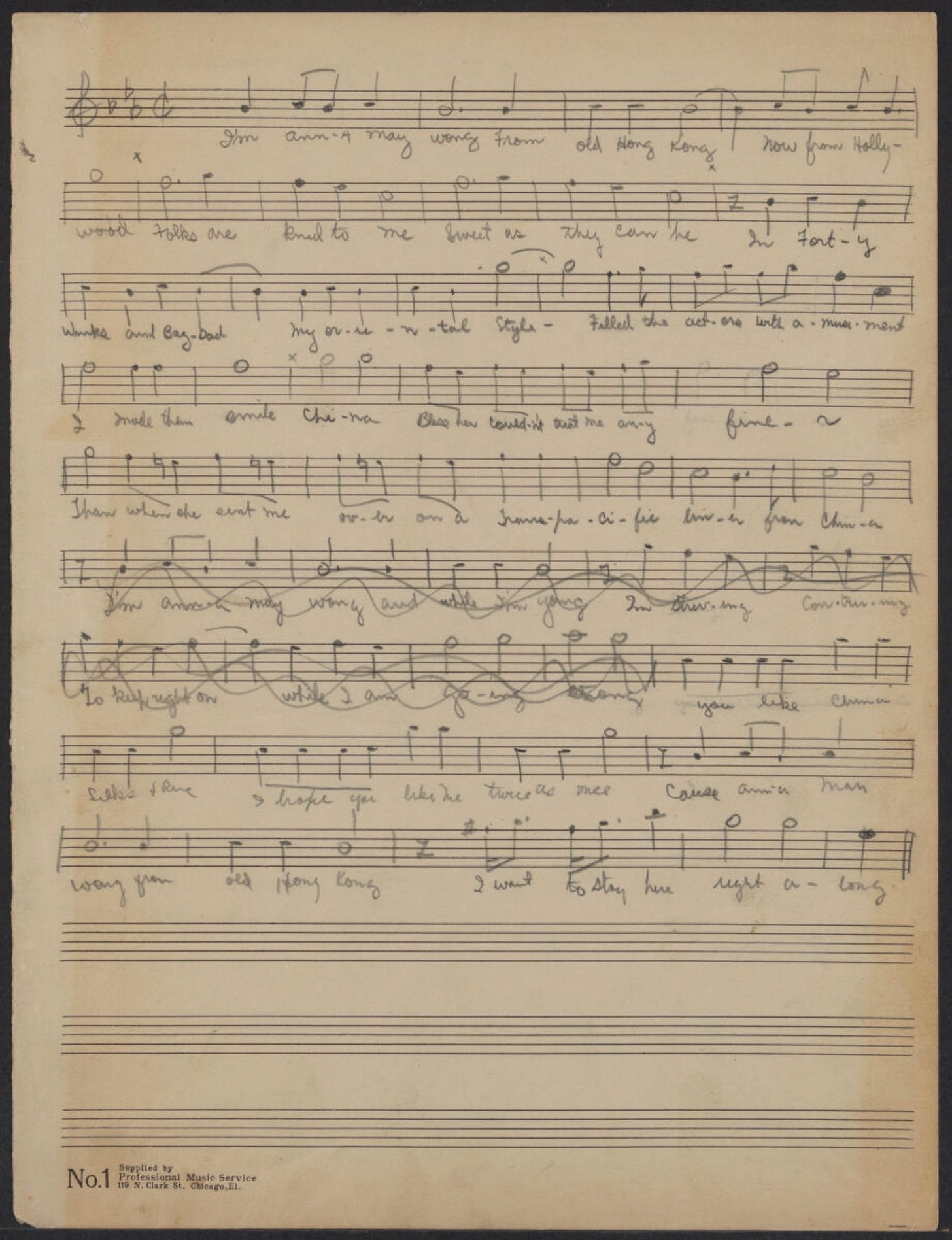

The exhibition includes items from Anna May Wong’s wardrobe, including the famous, gold-sequined dragon dress from Limehouse Blues, as well as the sheet music for the ballad “I’m Anna May Wong” and a collage by German artist Marianne Brandt. Could you tell us a bit about each of these pieces and how they’re incorporated into the exhibition? What was it like getting to handle precious items like the legendary dragon dress?

Anna May Wong is such an iconic figure, so I wanted to show parts of her that were less well known. Certainly, the Travis Banton dress is incredibly well known. For this exhibition, I decided to turn it around, so that viewers could see the clasps going down the back. This was in order to show that the iconic image of her in the dress was a construction, which required a laborious process of getting dressed. When I had a chance to study this in the Costume Institute, I realized that there were tiny tears at the elbows, and sweat stains. Up close, you realized how hard Anna May Wong was working to perform this glamorous image for the camera. Likewise, the sheet music for Anna May Wong’s cabaret act is a construct. It starts with the lines, “I’m Anna May Wong from Old Hong Kong” even though we know that she was born and raised in California. Even as she’s performing a made up story, I like that she’s singing it in her own distinctly American voice.

Brandt’s collage is interesting. It features Wong’s face alongside other glamorous images of women from magazines, cut and layered in an abstract way across a large sheet of paper. There are other materials too, including transparent material, and a lens. I think the work is a commentary of sorts about glamor and the screen, a kind of taking apart of constructs of beauty. It’s also a rare example of racialized types appearing on a work by an artist from the Bauhaus movement, on the eve of World War II. Even as it reverts back to European tropes of exoticism, I like the broken glances of each woman.

I was particularly drawn to the artwork in the show by Patty Chang. I love her performance in Melons (at a loss) where she chatters on about a commemorative plate—a piece of porcelain—and then proceeds to slice off her left breast and scoop out its flesh (embodied by a cantaloupe) into her mouth. It’s hard to look away from this bizarre scene or stifle a laugh; as an unsuspecting visitor, you wind up consuming the artist consuming herself. If there is a corollary to white men thinking about the Roman Empire at least once a week, maybe it’s Asian women thinking about Patty Chang eating her melons! That video replays on a loop in my brain. How do you see Chang’s work in the context of the show?

The stuff of chinoiserie is so beautiful and seductive that it prompts feelings of possession: I’d love to have that cup and saucer, or own that beautiful china. That’s certainly something that arises when you walk through the exhibition and see all of these beautiful luxuries. Patty Chang’s work undercuts that, forces us to take a step back and realize that there was a cost to this exoticism, inscribed into the bodies of Asian women. Exoticism is a powerful, seductive lens that she turns back on itself to reveal its distortions. But she does it in such an absurd and humorous way that hits you right in the pit of your stomach. It’s brilliant.

What do you hope visitors take away from the exhibition?

The feminist revision of the exhibition title is not tied to a specific object, but aimed at prompting a different way of looking at the world. To look and to see is a powerful not passive action. Looking, and looking with a sense of curiosity at works of art is always the main goal. I don’t expect people to read all of the labels or the catalog. But if I overhear a visitor saying, wow, what is that? Or, what is that doing here while stopping to look again, then I feel like that’s a step in the right direction.

Monstrous Beauty is on exhibition at The Met through August 17 and free with museum admission. Plan your visit here. If you’re unable to see the show in person, you can watch this beautifully produced video tour with Iris Moon. Additionally, Anne Anlin Cheng wrote an incisive review of the exhibition for Hyperallergic and Cindy Kang contributed the essay “Glamour as Resistance” on how AMW used fashion to define her image and legacy.

Anna May Wong, ah best dressed leading lady. :) Thank you for the heads up about the Met exhibit. And appreciate the reminder that Great Britain picked up porcelain from China among so many other things through the Silk Road...the association with porcelain does explicitly make sense with exoticized associations, which seem positive and innocuous, but can take a turn into objectifying and creepy.