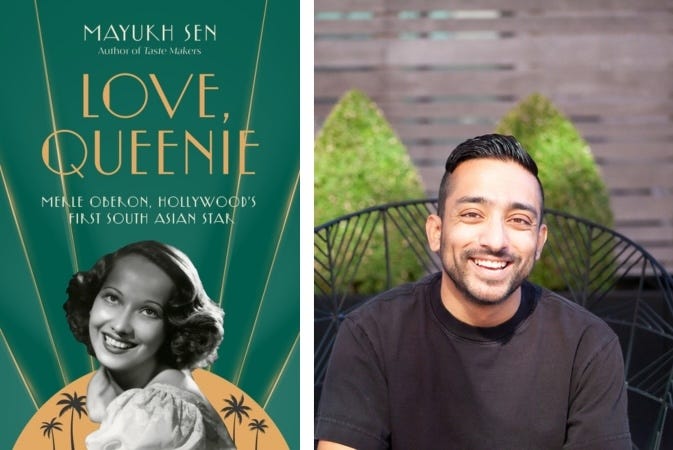

Love, Queenie

reclaiming Merle Oberon, quelling old rumors & Hollywood’s race problem with Mayukh Sen

Merle Oberon, the mixed race South Asian actress best known for playing the lead in Wuthering Heights (1939) opposite Laurence Olivier, has long been a source of mystery and controversy in Hollywood lore. I came upon her story in my research on Anna May Wong and was immediately fascinated. For most of her career and life, Oberon’s handlers coached her to conceal her South Asian heritage and pass as white so that Hollywood studios would cast her in leading lady roles. It was the path of least resistance in a system set up to prioritize whiteness, and despite Oberon’s success, hiding her true identity came at a great personal cost.

When writer Mayukh Sen reached out to me a few years ago, I was delighted to learn that he was already deep into researching and writing a biography of Oberon, which is now just a few weeks from publication. It turned out we had a lot to talk about—the challenges of writing about the Asian figures Hollywood would rather forget, archival adventures at Margaret Herrick Library, and the New York publishing scene—so it’s not hard to see why we became fast friends!

I was honored to read an early copy of Love, Queenie and sped through its pages while on vacation in Hawaii last year. The book has already received starred reviews from Publishers Weekly, Booklist, and Kirkus, and is shaping up to be one of the year’s most highly anticipated biographies. One of the things I was most struck by was the love and care Mayukh took in approaching his subject and how his thorough research finally reframes her story and ditches the more sensational tales of yore—the kind told by Hollywood writers who were simply out to make a buck on a dead celebrity’s name. In advance of the book’s publication, we sat down to talk about Oberon’s legacy, his original research that debunks numerous old rumors, and his top Merle Oberon film picks.

We first bonded over the personal connection we each feel towards our biography subjects. In fact, you write beautifully about discovering Merle Oberon as a teenager in the introduction to Love, Queenie. Could you tell us how you first learned about Merle and what drew you to her? When did you know you had to write a book about her?

Thank you for the kind words, Katie! I did, indeed, first come to Merle’s work as an Oscar-obsessed teenager, when I learned that she was the first performer of color—and Asian actress—nominated for an Academy Award through her Best Actress nod for The Dark Angel (1935). Reading her backstory, I was stunned: Here was a mixed-race, South Asian actress, born in Mumbai and raised in Kolkata (the city where my dad, who was Bengali, was from), who made it big in Hollywood. (Keep in mind this was around the time that many of us thought Freida Pinto was going to be a huge star on the heels of Slumdog Millionaire.) I couldn’t quite believe someone from the same part of the world as myself gained entry into an industry that was often hostile to our kind, and so long ago. Knowing that Merle had to conceal her maternal South Asian heritage and Indian birthplace to “pass” for white broke my heart. Watching her as Cathy in Wuthering Heights (1939), I was captivated by her screen presence, especially considering the pain she lived with in her private life.

When I first signed with my literary agent, William Callahan, back in 2017, I told him I wanted to write a biography of Merle. I was twenty-five then, and I certainly didn’t have the skill to write a single-subject biography of such a morally complex figure. My writing life would take a detour, and I’d spend the next few years writing about food professionally. But after my first book, Taste Makers (2021), came out, I decided I owed it to myself to pursue this passion project of mine—even if it meant I was stepping away from my career as a food writer, a job I came to love.

Merle Oberon is often seen as a controversial figure, not only in Hollywood, where the rumor mill loved to gossip about her, but also within South Asian and Asian American communities today. Most of the animus towards her has to do with the fact that she passed as a white woman and denied her South Asian heritage in order to play leading lady roles in Hollywood films during an era when the Hays Code ban on interracial relationships was strictly enforced. And yet no one seems to call out the studio executives who coerced Merle into this position in the first place. Your book offers a much more nuanced and sympathetic portrait of her situation. How did you come to this understanding?

I think it’s fair to say that very few people in my generation know about Merle—and those who do seem to malign her at every turn, saying she was a traitor to her race because she passed for white. You rarely see her discussed in the same breath as luminaries like Sessue Hayakawa or Anna May Wong. (Boris Karloff, who was Anglo-Indian, is also often elided from these narratives about Asian representation.)

We saw this cruelty play out during the 2022 - 2023 Oscar season, when Michelle Yeoh became the second Best Actress nominee of Asian descent in the category after Merle. But the brevity of cultural memory—along with the tendency to impose present-day morals onto history—resulted in some outlets erasing Merle entirely or engaging in semantic contortions by saying that Yeoh was the first “Asian-identifying” nominee in the category. It was especially dispiriting to see those who anoint themselves to be spokespeople for the Asian American community disparage Merle in the name of empowerment. Her exclusion reflects the thoughtlessness with which mixed-race members of the Asian diaspora are treated, as well as the ways in which South Asians get minimized in broader conversations about Asian identity.

In writing Love, Queenie, I wanted to understand why Merle was compelled to pass for white—and to question the extent to which doing so was even her decision. The few parties who are sympathetic to Merle usually reference the Hays Code as the main imperative for her needing to pass. But there was a wider, sociopolitical factor that was influencing her decision: America had imposed a federal ban on immigration from India starting with the Immigration Act of 1917, while a 1923 Supreme Court ruling declared Indians ineligible for naturalized American citizenship. These policies were the result of long-festering societal animus towards South Asians—many of whom were pejoratively called “Hindus,” regardless of their religion. (That’s a word the press used for Merle when she first came to America in 1934.) I felt it necessary that a biographer connect the dots and show just what was at stake for Merle.

Love, Queenie is the first book on Merle in more than 40 years. Charles Higham’s 1983 biography (if it can even be called that), Princess Merle, spread a number of pernicious rumors about the actress and her background. For example, he claimed that not only was she of mixed British and South Asian heritage, but also part Māori—which I inadvertently repeated in a post on Half-Caste Woman but have since corrected. Thankfully, you dispel the confusion around Merle’s origins on the very first page. How did you go about setting the record straight? What new sources or family members were you able to track down? And what are some of the most outlandish claims that your book debunks?

I wish everyone else exhibited your level of care when writing about Merle! It’s true: There has, prior to my book, only been one biography of Merle, written by Charles Higham and Roy Moseley. I salute their efforts (their book, published four years after her death, was the first to confirm her true origins), and I don’t want to besmirch fellow writers—the work we do is hard; their hearts were in the right place. But Higham’s track record is famously spotty when it comes to facts, and that sloppiness extends to his project on Merle. Despite reportedly having Merle’s birth certificate, Higham and Moseley did not seem to be aware that the woman they referred to as Merle’s mother, Charlotte, was actually her grandmother, while the woman they believed to be her half-sister, Constance, was her biological mother (something Merle herself likely did not know). This became public knowledge in 2002, with the release of the filmmaker Maree Delofski’s documentary The Trouble with Merle.

After speaking to Delofski, I worked pretty doggedly to track down Merle’s surviving family from India, supplementing that with archival research (which included her personal papers and immigration documents). After pounding the pavement, I found them, and they told me a great deal about the alienation Merle faced having grown up as a poor mixed-race girl in India and her relationship with her mother—who’d given birth to Merle when she was only fourteen. They clarified Merle was not part Māori at all as Higham and Moseley claimed; her grandmother was Sinhalese, from Sri Lanka, and her mother was half-Sinhalese and half-white.

I also wanted to test some of the other claims that Higham and Moseley made that raised my eyebrows. If they didn’t stand up to my scrutiny, I either refuted them directly in my book or didn’t give them any airtime. Higham and Moseley suggested that she could not bear children because of a bout with cancer in her twenties, but I found evidence—contained in my book—that pointed to other reasons for her infertility. They speculated that Merle commissioned a painting of her “mother” Charlotte (who was, again, her grandmother) in 1949, years after Charlotte had died, but asked the portraitist to lighten the skin to defuse any speculation of Merle’s origins. Though I did indeed find a copy of that painting from her family, there was no evidence that she intentionally asked for the skin to be lightened. People often point to Charlotte pretending to be Merle’s maid when they moved to London in 1929 as evidence of Merle’s selfishness—but I found little to suggest that ploy was even the eighteen-year-old Merle’s idea; it was quite likely Charlotte’s, as she wanted Merle to succeed and escape poverty. Many people also seem to believe that Merle intentionally lightened her skin. But my research pointed to studios forcing that upon her, rather than her voluntarily seeking such treatment out herself. A number of these claims are weaponized against Merle in service of a narrative that she was, as I said earlier, a traitor to her race. Articles and podcast episodes on Merle from the past five years almost always work from Higham and Moseley’s biography and repeat some of its more spurious claims. I wanted to dispel those falsehoods so her memory can be at peace.

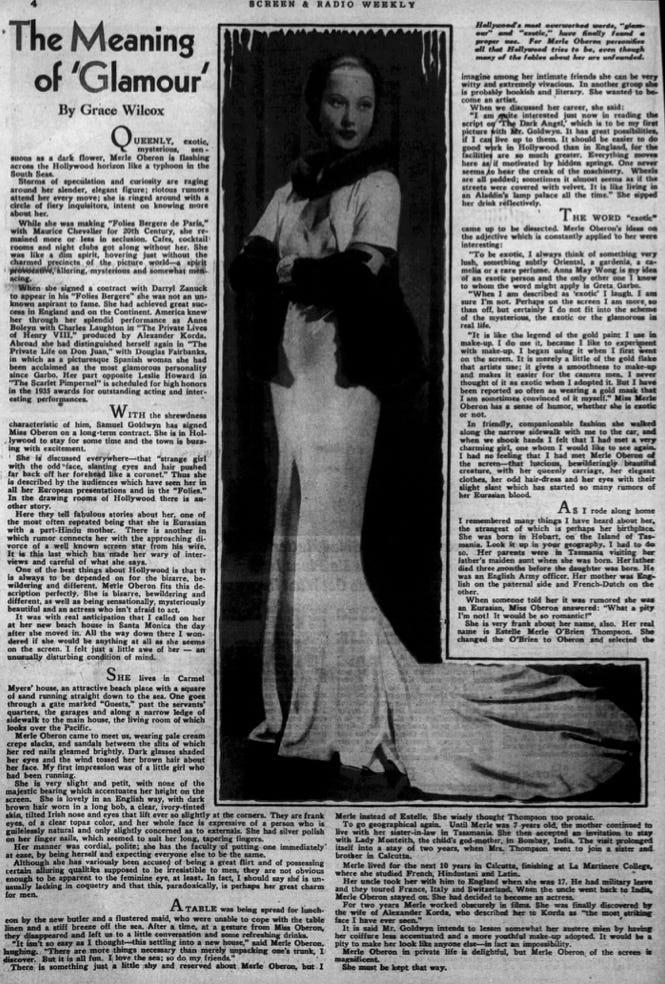

As a mixed race person, I have a lot of empathy for what Merle went through. The U.S. has a bad track record of forcing mixed race people to choose one racial identity that fits neatly in a box. The unspoken racial hierarchy that we all live under doesn’t know how to deal with the complexity of multiracial people. Reporters were constantly probing Merle and making insinuations about her background, as if to catch her in a lie.

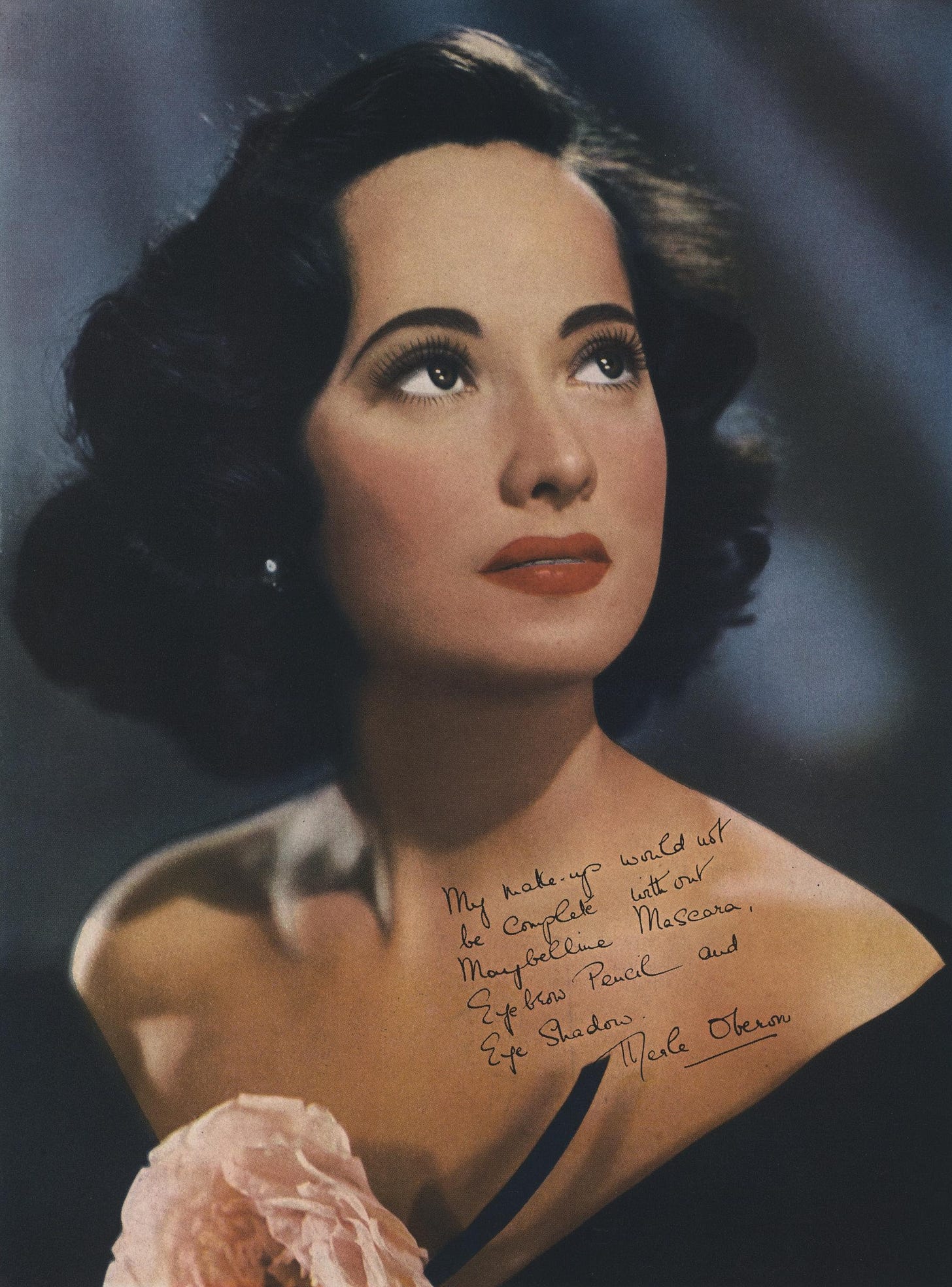

I ran across one of these interviews in my research on Anna May Wong (which you told me you also found and used in the proposal for your book). The reporter broached the word “exotic” and Merle demurred, saying, “When I am described as ‘exotic’ I laugh. I am sure I’m not.” She added that, “To be exotic, I always think of something very lush, something subtly Oriental . . . . Anna May Wong is my idea of an exotic person.”

Merle responded so deftly, it almost takes my breath away. But it also makes me reflect on the lengths she had to go in order to keep up the charade of whiteness (and not necessarily by choice). I can imagine how stressful and painful it must have been for her. Did you come across any research materials that revealed what Merle herself thought about having to deny her Asian heritage? Or that captured the emotional and psychological toll it took on her and her family?

I call Merle “a biographer’s nightmare” in the acknowledgments of my book because her interiority is so hard to access; she was an unreliable narrator of her own life. Almost all interviews she gave about her upbringing referenced a false biography publicists had written for her, claiming she’d been born in Tasmania to white parents. But I learned, through my reporting and research, how to read between the lines. Early in her Hollywood career, you see emphatic rejection—like the kind you point out—of the suggestion that she is anything other than white. But in later decades, as America’s animosity towards South Asians eases, you notice a shift. Around 1946, with the passage of the Luce-Celler Act—which permitted legal immigration of Indians to America (though subject to a quota), as well as their naturalization—you see her tell the press that she wants to go back to India. She makes declarations in subsequent years that she will now pursue American citizenship; what we now know is that she was at long last able to do so due to changes in federal law.

After 1965—which is the year that the Hart-Celler Act abolishes that previously-imposed quota on Indian immigration to America, and the country embraces Indian-born talents like Ravi Shankar—you sense a conflict: In some archival sources, she very loudly denies that she is a “half-caste Indian,” even though her skin has gotten noticeably darker with age. A 1973 Interview feature on her leads with the headline Merle Oberon is not a Hindu, and she laughs off such a claim as an absurdity. But around that same time, she’s wearing more clothing from India out in public, sharing her favorite recipes for curry with the press, and signing on for roles to play Indian women (something Sam Goldwyn never would’ve let her do in 1930s Hollywood).

To me, so much of this speaks to the tragedy of Merle Oberon: America, this country Merle came to in search of a better life, became more hospitable to aspects of Indian culture it was once so vehemently opposed to. But it’s not as if Merle was in a position to publicly come out and tell everyone that she’d been lying for decades. Her life was built on a lie she did not create herself. What is remarkable—and makes her story so much more than a mere tragedy—is that she kept living, and fought to pursue happiness and stability on her own terms.

What do you hope readers take away from your biography of Merle Oberon aka Queenie?

My book is partially a response to the effacement of Merle. I hope that people will no longer reduce her to a “technicality” or footnote in Oscar or Hollywood history. I want my readers to do the hard, compassionate work of understanding her instead of falling prey to the lazy, incurious impulse of judging her. People buy into the fallacy that Merle led a charmed life because she passed for white, but my reporting revealed a more uncomfortable truth. I want my readers to grasp that it was more than just the Hays Code that forced her hand, and that there were larger structural elements—especially in America—that made her feel that passing was the only option. I have no desire to elevate her to sainthood; she’d be boring if she were perfect. She had foibles like we all do. I wanted to portray the full spectrum of her humanity.

But my primary objective with this book was to get people to appreciate Merle as an artist. I want my readers to see what I responded to in her work when I first came across her in high school. Growing up in the aughts, I used to read Oscar blogs avidly, and a common opinion I found of Merle’s work was that she lacked the acting ability of a Stanwyck, Crawford, or Davis to merit celebration. I disagree with those assessments of her acting. Her talent is especially impressive when you consider—as I hope people will do after they read my book—that she came from so little. When you understand her journey, you appreciate her art more.

I just watched Wuthering Heights (1939) for the first time. Merle is so beautiful and spellbinding in it. For those interested in her filmography, which three films would you recommend people start with?

I’m so happy you liked her in it! People are hard on her version of Cathy, but I think she’s wonderful. Here are three movies from her filmography I’m especially partial to:

’Til We Meet Again (1940): This “woman’s picture” was the first film Merle made under contract at Warner Bros., where she landed after she and Sam Goldwyn decided to part ways professionally (Wuthering Heights, despite its reputation, wasn’t quite the box office success Goldwyn had wanted). Wuthering Heights was a real test of her dramatic skills, and I’d say that ’Til We Meet Again shows just how much Wuthering Heights forced Merle to mature as an actress: In ’Til We Meet Again, Merle plays a woman on a cruise ship who’s dying of a heart condition. She falls in love with a man (George Brent) who’s a convict awaiting execution. Neither knows of the other’s secret. Some of Merle’s strongest performances have this parallel to her real life—she plays a woman who is hiding something, and living despite it—but this might be the most heartbreaking.

Lydia (1941): This was a vehicle that Merle’s first husband, Alexander Korda, fought to secure for her, and it really does feel like a love letter to her talents. She plays a capricious, mercurial woman named Lydia MacMillan, who falls in love with a variety of men but, in old age, ends up alone. Though you can see the grubby paws of the Hays censors all over this movie—it effectively punishes Lydia for being a woman who has no regard for tradition—Lydia gives Merle so many notes to play, and she aces them all. It’s a real showcase for her; this feels like her most demonstrative dramatic performance.

Dark Waters (1944): I love this taut, gripping little thriller, where Merle plays a woman who improbably survives a maritime accident that claims her parents. She is then the target of an extortion attempt from people who are masquerading as her extended family members. The film’s first scene, in which Merle wakes up in her hospital bed, contains some of the most stunning acting of her entire career. Some people have criticized Merle for never being able to let loose in her acting. That scene proves she was capable of pushing herself.

Mayukh Sen’s biography of Merle Oberon, Love, Queenie, is available for pre-order here. If you’re in New York, you can catch his book launch at McNally Jackson Seaport with Michael Schulman of the New Yorker on March 5 at 6:30 pm. He’ll also be doing a talk, book signing, and screening of Wuthering Heights at the Museum of the Moving Image on March 23. Follow Mayukh on Instagram at @mayukh.sen.

Terrific unknown information for me ... Thanks for your dedicated research Katie... So glad I saw you at Los Angeles Chinese museum dedication for AMW. The beat goes on... Victor. Panay Island Philippines.

Thank you also for sharing something about another author's work and giving us a glimpse of another really intriguing life story! Very interesting to find out how Merle had been able to "pass," and all the pressures placed upon her by Hollywood studios and then reactions from people within her community.