In May 1924, a nineteen-year-old Anna May Wong traveled to Banff, Canada—her first trip out of the country—to shoot The Alaskan, a film starring Thomas Meighan, a rugged hunk known for his draw with the ladies. Famous Players-Lasky (later Paramount Pictures) decided it was easier, and likely cheaper, to sub in the Canadian landscape for Alaska than to travel the cast and crew all the way there. While Anna May was filming on location, she wrote home to the Los Angeles Times in a “breezy letter” of the goings-on up north:

“Cheerio, old top. I am trying to be very English, you may observe, but it doesn’t do any good. My thoughts are too American and Chinese, I guess. But I am enjoying everything there is to enjoy here, including the weather, because I have a hunch it is rawther [sic] warm down South, don’t you know. Sorry I couldn’t go on to Alaska, because I might send you a gold nugget, eh, what?”

“Everything and every one are just perfect,” Anna May wrote. “I think the picture, in which Thomas Meighan is starring, you know, is going to be a winner. So far the locations have been simply gorgeous, and I think the rest will be, too. It seems as though there isn’t an ugly spot anywhere in the landscape up here. Though I must admit I should like a peep of real California sunshine, for it manages to rain sometime during the twenty-four hours on the sunniest days here. We have one saving thing, though—the long daylight hours. It seems so funny to have dinner at 10:30! We have no idea of regular hours now.”

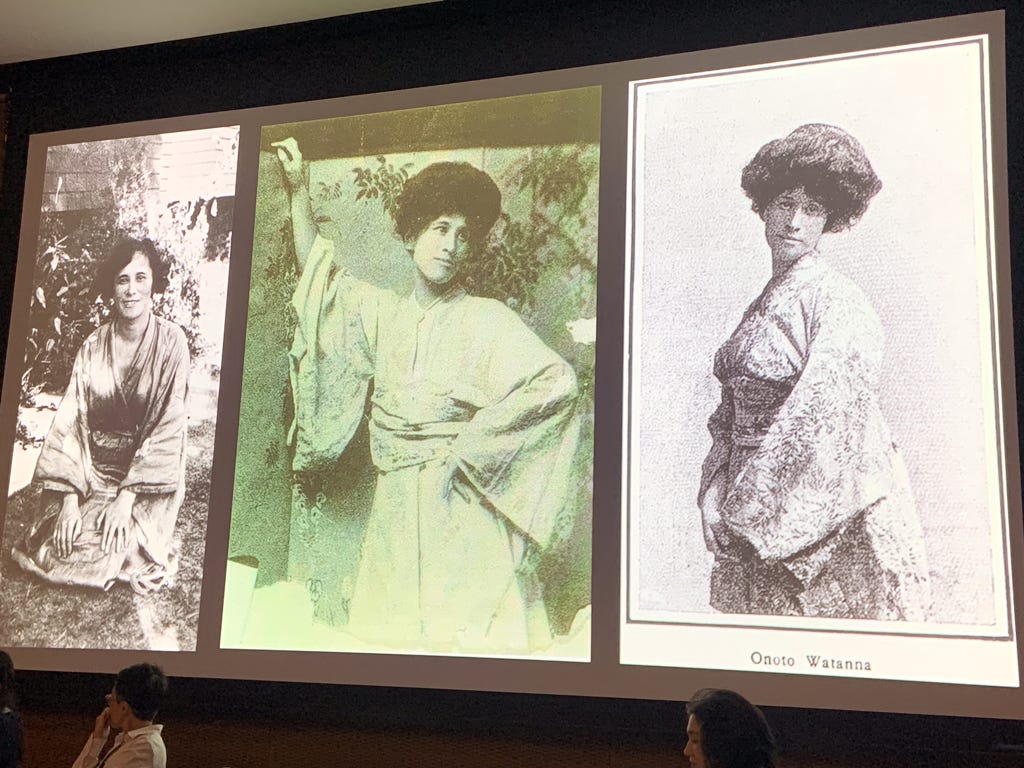

I can attest to all the details AMW describes—the unexpected sunshowers, the long days drenched with light, the breathtaking vistas of the Canadian Rockies—because I’ve just been to Banff and back. Last week I flew to nearby Calgary to attend Onoto Watanna’s Cattle at 100, a three-day conference focused on the life and work of writer Winnifred Eaton. Winnifred, who I wrote about briefly in a previous dispatch on Asians in young Hollywood, is a fascinating figure.

Born in 1875 in Montreal to a Chinese mother and an English father, Winnifred had an exceedingly rare parentage for her time. When she came of age, she followed in her older sister Edith Eaton’s footsteps and became a writer. Yet while Edith adopted a Chinese pen name, styling herself as Sui Sin Far, and wrote about the Chinese working-class in North America, Winnifred never publicly claimed her Chinese heritage and instead fashioned herself as a Japanese writer, inventing the persona of Onoto Watanna.

As Onoto Watanna, she wrote stories and a number of best-selling novels that were huge commercial hits in the U.S. For example, A Japanese Nightingale, her second novel, reportedly sold 200,000 copies and was adapted for the stage, opening at Daly’s Theatre on Broadway in 1903. Later in her career, Winnifred migrated to Hollywood and was brought on by Carl Leammle to lead Universal Pictures’ East Coast scenario department. She oversaw and contributed dozens of films at Universal, including East Is West featuring Lupe Velez in yellowface and the first screen adaptation of The Phantom of the Opera starring Lon Chaney. And if that wasn’t enough, around this time Winnifred departed from her early Japanese themes and penned a few prairie novels like Cattle that were set in the great plains of Alberta, Canada.

One of the unique features of Winnifred’s writing, and the thing that drew me to her in the first place, was the way that her stories broach the topic of mixed race identity and interracial romance. At the turn of the 20th century, she was one of the only writers creating work that explored the lives of mixed Asian characters. Her stories, like the ones contained in the collection "A Half Caste" and Other Writings, which were published in magazines like Harper’s Monthly and Ladies’ Home Journal, often subvert the typical Madame Butterfly narrative in subtle ways. Winnifred was a self-made woman, a working girl who wasn’t afraid of hard work, and so her writing also has a feminist bent to it.

The conference in Calgary brought together an eclectic mix of academics, artists, filmmakers, and writers, as well as Winnifred’s descendants, including her granddaughter and biographer Diana Birchall. Each day’s lectures proved to be absorbing and shed light for me on Winnifred’s storied career, her penchant for tall tales, and her sometimes confounding attitudes on race. Did Winnifred and Anna May ever cross paths in Hollywood? It’s certainly possible, and now that the question has been raised, I feel it’s my duty to find out.

It was especially fun to be in a room full of people all interested in the same subject—and who, not surprisingly, were often mixed Asians like me. Sadakichi Hartmann, the other mixed Asian of literary renown, also came up in conversation regularly. Some of us laughed at the fact that Sadakichi had found a way to butt into Winnifred’s conference. How like him to try and steal the show!

If you’d like to learn more about Winnifred Eaton aka Onoto Watanna, her entire body of work lives in the digital Winnifred Eaton Archive, a project directed by Mary Chapman at the University of British Columbia, while her physical papers are housed at the University of Calgary and fully digitized in the Winnifred Eaton Reeve Digital Collection.

I was easily persuaded by one of the conference organizers that I should spend my free day in town making a day trip to the mountains. Calgary is just an hour and a half’s drive from Banff, so the chance to visit the place where AMW once made a movie was just too tantalizing to refuse. But I have to fess up. This wasn’t my first excursion to Banff. My husband and I actually went there on our honeymoon in December 2021. Yes, I found a way to turn even my honeymoon into a covert AMW research trip!

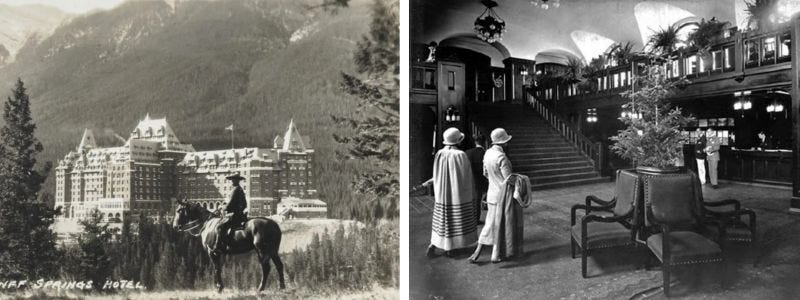

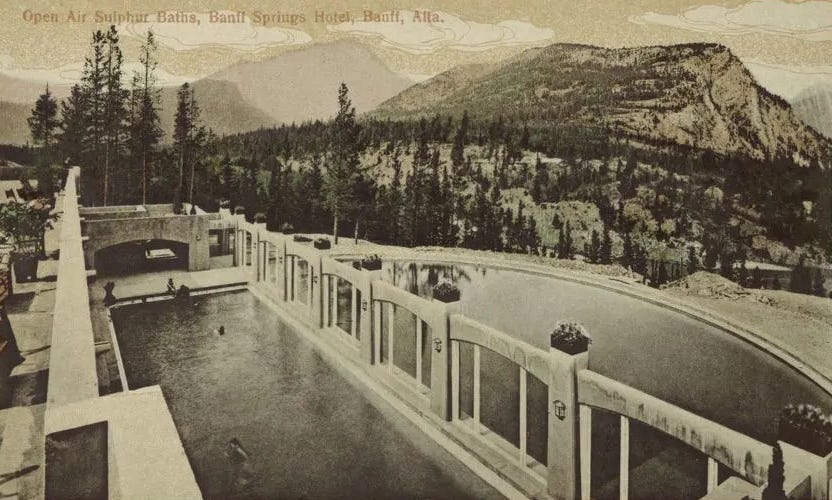

N and I trudged around in snow boots, taking in the sights of the winter wonderland. We gloried in the aprés ski delights of hot toddies and fondue, and bathed in the hot springs that originally inspired the Canadian Pacific Railway Company to turn Banff into a tourist destination. I had also planned for us to visit the majestic Banff Springs Hotel, where AMW and the rest of the cast and crew of The Alaskan were put up during the making of the film, but COVID restrictions at the time prohibited anyone who wasn’t staying at the hotel from entering the premises. Crestfallen, I had to settle for a bus ride past the hotel instead.

This time around, I finally got my chance to explore the castle-like interior of the Banff Springs (which is rumored to be haunted, but let’s just say I didn’t stick around long enough to find out). I made a reservation for high tea at the Rundle Bar and enjoyed the best view in all of Banff as I sipped my oolong tea, pinky up. I savored the moment in silence, thinking back to how Anna May must have spent her days in this mountain getaway.

According to co-star Estelle Taylor, on the days they didn’t work, she and Anna May could be found swimming in the hotel’s hot springs-heated pool. This despite the fact that AMW never learned to swim!

“Anna May cannot swim,” Estelle recounted to a reporter, “but she has all the nerve in the world—would dive from a height where I wouldn’t think of going.”

Other times, when AMW wasn’t called for in a particular scene, she might have joined cameraman and fellow Chinese American James Wong Howe and director Herbert Brenon on their perch at the top of the hotel, where they filmed scenes being acted out 1,000 feet below.

“I am playing an Indian Esquimox [sic] in the picture,” Anna May explained in her letter to the Los Angeles Times. This, of course, was another one of Hollywood’s questionable racial substitutions. Why hire an Indigenous actor to play the role of Keok, when a Chinese girl with braids could do just as well?

“We went over to an Indian stampede and roundup yesterday,” AMW continued, “very interesting but I am waiting anxiously to see the Indians when they have their grand pow-wow with war paint and everything—whoopee! We are having seventy-five Indians in the picture. They are smart Injuns, too—won’t have their picture snapped—says it makes them sick—unless they get paid for it!”

AMW’s use of the word “Injun,” today considered offensive, grates on the modern ear. In her early career, she was often complicit with Hollywood studios’ racialized typecasting, whether she was playing fainting Lotus Blossoms or masquerading as American Indians (a role she also assumed in 1924’s Peter Pan as Water Lily). But her line about the local Indigenous people wanting to get paid for their work hints at a subtle feeling of solidarity. Why shouldn’t they get paid for a day’s work spent performing their culture for the cameras? And the idea of losing one’s soul to the camera or becoming sick from its sorcery was a well-worn superstition in the Wong household. AMW’s mother objected to her movie work for precisely that reason, but when her father saw the paychecks she brought home, well, he seemed to change his tune.

Copies of The Alaskan are no longer extant, so unfortunately we can’t assess the movie for ourselves. But gleaning the reaction from reviews, AMW’s prediction that it would come out a “winner” never came to fruition. The film was a total flop at the box office. “It hasn’t much to recommend it,” the critic for Motion Picture News stated. “Its plot offers very little compensation, being devoid of story interest, carrying little novelty and practically no suspense.”

The movie’s one saving grace was the natural wonder cinematographer James Wong Howe captured on film: “Its scenes are truly magnificent—and they have been caught from all angles. The mountain ranges, the vast expanse of snow—and other vistas of Nature in all her rugged beauty serve in providing a rich ocular appeal.” If you ever find yourself in Banff, you too will discover its rugged, astonishing beauty—the kind that occasionally compels even movie stars to write home about it.

Updates in Brief

This past week, fellow writer Aimee Liu and I sat down for a conversation on my book-writing process and our shared fascination with Asian Americans in early Hollywood—check out our full discussion on her Substack Aimee Liu’s Legend & Lore. Aimee is the author of numerous books, including her most recent novel Glorious Boy. She and I found each other on the interwebs and bonded over our many mutual interests. Aimee’s father, Maurice Liu, and her aunt, Lotus Liu, were both involved in the making of The Good Earth (the same MGM production that passed over AMW for the female lead and cast Luise Rainer in yellowface instead), which Aimee writes about here. And her father, to my surprise, also shows up as one of the background actors in AMW’s Daughter of Shanghai. The Asian American contingent working in Hollywood at that time was a small world indeed!

I always feel like I could talk shop with Aimee for hours, so we decided, why not invite others to join us? On Saturday, August 12, 3 pm EST, we’re hosting a virtual panel for Medium Day titled Heritage as Hook: How Two Asian American Writers Explore History on Medium. You can register for free here. We hope to see some of you there!

If you happen to be in the Boston area, you may want to take a detour to Cambridge and visit the Houghton Library at Harvard where the curator of the Harvard Theatre Collection, Matthew Wittmann, has recently acquired a collection of sheet music from AMW’s cabaret tour. Included among the collection are a the lyrics for Noël Coward’s song “Half-Caste Woman” translated into Italian. Some of the materials are currently being displayed in an exhibition called “Anna May Wong Abroad.” In a nice little coincidence, I got to meet the exhibition’s curator, Karintha Lowe, at the Onoto Watanna conference where she was also presenting a paper. The show at Harvard runs until August 30 in the Lowell Room gallery at Houghton Library. Catch it while you can!

Wonderful story about a wonderful woman. Can't wait for your book to be released.

I also have a bit of Asian in me coming from way back. But I doubt that is the lure. It's Anna and her courage, intelligence and character. Love the whole picture.

James Wong Howe was interviewed at length about the filming of The Alaskan, as part of a his career, which can be found on YouTube.

I did not hear a mention of AMW in the audio recording-but it may not be the whole interview. Here: https://youtu.be/NCDMGaS8vB0?si=HO_r1hYNM4SeWnqZ.

There are mistakes of identifying AMW in some of the publicity shots--not in this article, though.