Telling Her Story

filmmaking, Walter Benjamin & the challenges of being an Asian American actress with Yunah Hong

I recently got lunch with fellow New Yorker (by way of South Korea) and Anna May Wong expert Yunah Hong to talk about our favorite subject. As many of you may know, Yunah directed and produced the 2011 documentary Anna May Wong: In Her Own Words. Her film was one of the first sources I looked to for inspiration when I began my research for Not Your China Doll, so it was fun to compare notes and see that we had trod a lot of the same ground.

Yunah has also made films about Korean American actresses struggling to build their careers and Korean American multimedia artist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (who Cathy Park Hong wrote about in her book Minor Feelings). Throughout her work, one common theme emerges: a passion for telling the stories of Asian American women, especially those who have been forgotten by the mainstream.

Yunah, thanks so much for making the time to speak with me about your work! Your documentary Anna May Wong: In Her Own Words was one of the first things I watched when I began researching my biography Not Your China Doll. Can you tell us a little about your background as a filmmaker and how you came to the topic of Anna May Wong? What was it about her that compelled you to make a documentary about her?

I was born and grew up in Seoul, Korea. I moved to New York City to continue my education in the mid-1980s.

I made my first video “memory/all echo” in 1990. It is based on text from DICTEE written by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951-1982), a Korean American multimedia artist. The video premiered at Videoscape: New York Asian American Video Festival in 1991 and is distributed by Women Make Movies (WMM). Since then, I have been making videos and films with both narrative and non-narrative storytelling. My main interest and focus has been Asian American women and their art. I have made seven shorts and two feature length documentaries so far.

When I was a student, I spent most of my free time watching films, both foreign and American. I saw Shanghai Express (1932) and was struck by Anna May Wong who played Hui Fei, a mysterious but clearly determined woman. Even though she was not the lead actress, her strong presence in the film made me want to know more about who she was. I did some research about her and found out that she was born in the same year as my maternal grandmother. Though she was my grandmother’s generation, she soon had a very interesting life as a pioneer film star in Hollywood. At that time, I had not heard about an Asian film star in Hollywood in the 1930s. I read a few short written articles about her and her films but didn’t find much information about her life at first.

I continued to make films and videos, including a short documentary, Becoming an Actress in New York, in the summer of 2000, which is about three young Korean American women striving to be actresses in New York City. After finishing the documentary, I noticed that Korean American actresses had limited opportunities to be cast in film and television in the US. There was a lack of good roles for Korean or Asian American actors. I remembered how Anna May‘s career was limited by sexism and racism in Hollywood in the 1920s and 1930s in spite of her being the only visible Chinese American film star. I saw the same struggles for Asian American actors even eighty years later. I wanted to say something about that. So I jumped back in to do research on her around late 2000. I didn’t know how long it would take to make a media work about her or what form it would take in the beginning. I just had a huge urge to embark on the project.

During my research, a photo of Anna May in her teenage years grabbed my attention. Because she looked like the girl next door in the photo. As a woman, I had already gone through my young adolescent years but was intrigued to find out how this girl next door became the most photographed, sophisticated, cosmopolitan woman we now know about. Also, I really wanted to know Anna May, the person behind her cinematic images. As the production of the documentary progressed over the years, my initial aspiration to make the documentary changed. The more I discovered about her life, the more I was convinced that Anna May could serve as an inspiration for my daughter who is the first generation of Asian Americans in my family. I was making the documentary for her and her generation of women.

How did you conduct your research for the documentary? Why was it important to you to tell AMW’s story “in her own words”?

I started researching Anna May in New York City where I live. I found a lot of information about her career at the New York Public Library’s Performing Arts branch and research library on 42nd Street. I traveled to UCLA’s media library where I watched their collection of her feature films (before YouTube came along) and documentary footage of her trip to China in 1936. I also researched her movie stills and studio files at Margaret Herrick Library in Los Angeles. The research helped me to write a documentary proposal and I started to submit it for public funding. Soon I got a small New York State grant for further research.

I also went to Yale University Library, University of Wisconsin Media Library, National Portrait Gallery, and British Film Institute in London. As the internet expanded and more digital information became available, I found stills and her rare silent films at European library sites.

At the same time, I was working at an outreach program at Korea Society as a university lecturer visiting different universities. Whenever I visited a university, I checked its library collection for more information on Anna May.

My priority for the documentary was interviewing people who knew Anna May personally. I sent out letters and emails to people who might have known her. I also reached out to Asian American actors for their insights about her and scholars who were doing research, writing a thesis or book about her. It worked, as one email led to another email. So I found potential interviewees and contacted them for interviews. I also got a lot of rejections from people who didn’t want to be interviewed by me. Or they simply did not have any knowledge of Anna May. In some instances, it took several years to arrange for an interview.

As soon as I received production funding, I shot the interview, edited work-in-progress, and applied for funding. I repeated the same process to find more people who might have known Anna May personally. It took almost ten years from the start of research to finishing the documentary. Now, most of the people who I interviewed for the documentary have passed away, including Susan Ahn Cuddy, A. C. Lyles, Conrad Doerr, and Jack Cardiff who knew her personally. I also want to mention Richard See and Kim Chan who were not in the final documentary but gave me their time to interview them about their family and Anna May. I’m really grateful for their invaluable interviews.

Right from the beginning of the documentary, I knew that I couldn’t interview Anna May since she passed away in 1961. One of the ways to give her a voice in the documentary was by recreating Anna May’s words either as a voiceover or as reenactments. Fortunately, there are many letters Anna May wrote in her lifetime and many interviews she gave throughout her career. I used those letters and interviews to write her monologue in the documentary. I did casting calls in both New York and Los Angeles to find an actress to play Anna May. Doan Ly, who played Anna May in the documentary, did wonderfully embodying Anna May in her reenactment for the documentary. It was important for me as a documentary filmmaker to present source materials of what Anna May said or wrote in her life faithfully for the audience without alteration, so they could get to know about her life.

More recently, you’ve been working on a short titled Parlor Game: When Walter Benjamin Meets Anna May Wong, about German philosopher Walter Benjamin’s much talked about meeting with the movie star in Berlin. This has always been one of my favorite episodes from AMW’s time in Germany! I also tried my hand at bringing it to life in my book. How did your specific vision for this short come to be? And when can we catch a screening of it?

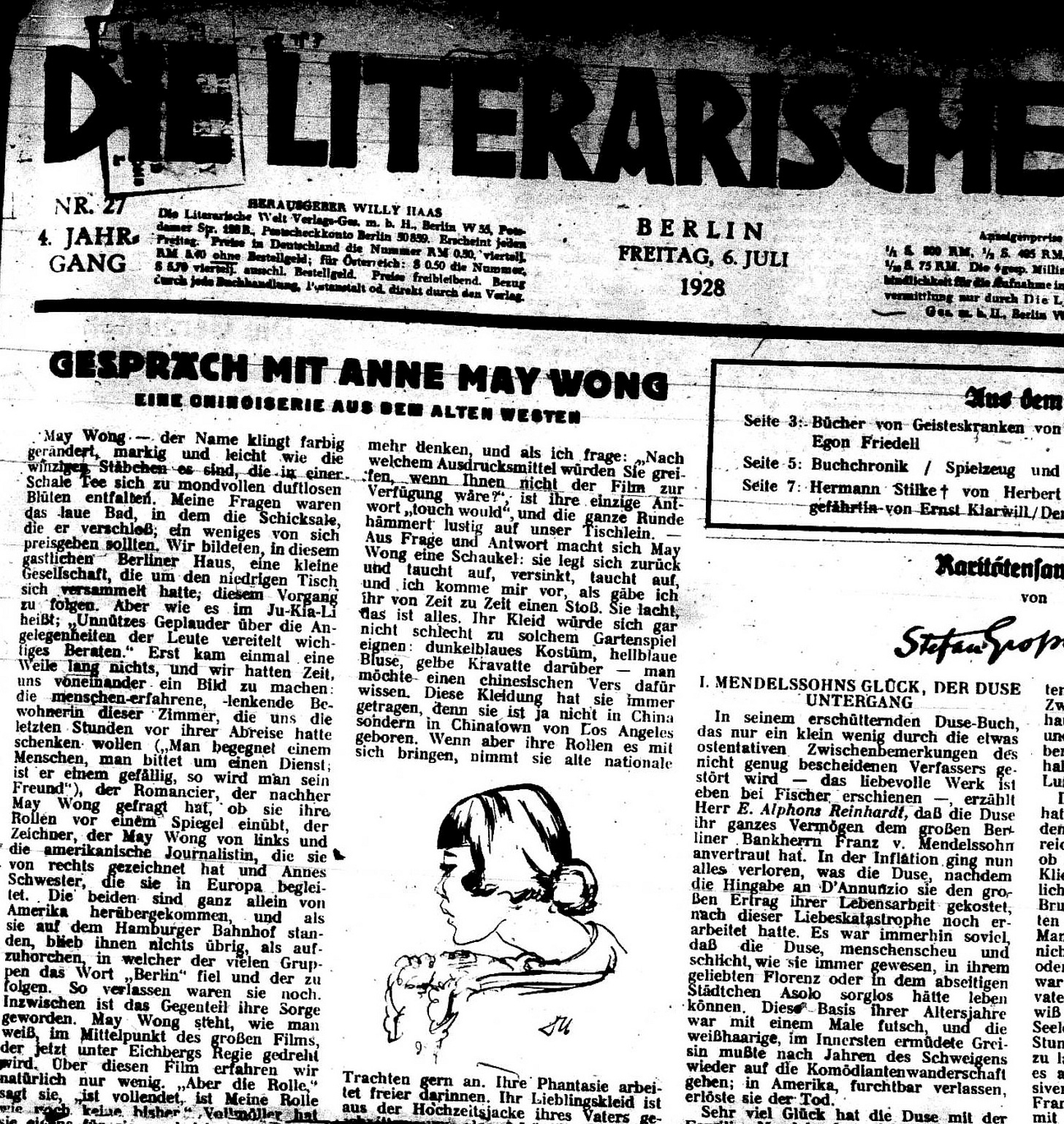

When I made the documentary, I had several materials that I could not include in the documentary but was interested in developing further as part of a narrative film. This short historical film is one of those ideas that I had in my head for many years. I wrote the short script and had an opportunity to go into production with actors last year. As you know, Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) had a conversation with Anna May in a Berlin parlor in June 1928. Later, he wrote an article about it for Die Literarische Welt, which was published a month later. Now Benjamin is regarded as a major 20th-century philosopher and Anna May is the first Chinese American actress who reached worldwide fame in the 1920s and 30s.

At the time of their meeting in Berlin in 1928, they were going through different phases in their lives: At the age of 36, despite being a published author with a doctorate degree, Benjamin was struggling as a freelance journalist. He and his family moved into his parents’ house due to their financial difficulties. At the same time, Anna May, at the age of 23 had appeared in seven films the previous year (1927) but made a gutsy career change in March 1928. She moved to Berlin with her sister Lulu to make a film for UFA. She had just finished her first German silent film, Song, at the time of their meeting.

My film imagines what went unspoken when Walter Benjamin met Anna May in a Berlin parlor in 1928. Based on the brief description in the article, besides Walter Benjamin and Anna May, I created several other characters including a novelist, an artist, a translator, and Lulu.

I hope to premiere the film next year at film festivals here and abroad, including Europe and Asia. I hope to meet audiences who are interested in Anna May, Walter Benjamin, and Berlin in 1928.

You have now been producing work about Anna May Wong for more than 20 years. What keeps you coming back to her life and career?

My reason to keep going is that I have something to say about Benjamin's meeting with Anna May. Whether it is mostly my imagination, a fictional story based on his article, I want the audience to think about two 20th-century luminaries. Their importance in history is more relevant now than in 1928. I want to use this short film as a concept film for a narrative feature in the future about Anna May's time in Berlin. Through Anna May as a young foreigner in Germany, I can reflect on my own experience as a young foreigner in New York.

You can stream Anna May Wong: In Her Own Words on Amazon Prime Video or purchase the DVD through Women Make Movies. Yunah’s other films, Between the Lines: Asian American Women’s Poetry and memory/all echo, are also distributed by WMM.

Dear Ms. Salisbury, Thank you very much for this wonderful, detailed article! Much appreciated! Sincerely, Michael Leigh Cook (aka Walter Benjamin).

Katie, thank you for another enlightening essay on the life of Anna May Wong.

The conversation with the director of "Anna May Wong, In Her Own Words" is revealing. It's wonderful that the documentary is now readily available.

Thank you for the info on viewing the documentary.

Wong's story is not static, but dynamic. It will continue to be expanded.