I heard the news of the Atlanta shootings while watching Rachel Maddow on MSNBC. The first words out of her mouth were that 7 people had been killed in a shooting in Atlanta. I held my breath and waited for the other shoe to drop—somehow I knew instinctively that this was not your average mass shooting event (as much as it disturbs me to call any mass shooting and the loss of life it causes “average,” the reality of living in the United States of America today is that mass shootings have become commonplace occurrences). Maybe I had been primed to expect something like this to happen. An increasing number of violent hate crimes against Asian Americans and the escalating rhetoric used to scapegoat us for the suffering inflicted by a global pandemic had put us on notice.

When the words “Asian massage parlor” flashed across the screen my worst fears were confirmed. It’s happening, I thought. Within minutes the death toll was revised to 8 people, 6 of whom were Asian women. Instead of feeling the customary emotions of disgust, anger, and sadness that I have experienced in response to so many events over the last five years—the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, the separation of immigrant children from their families at the border, the testimony and later confirmation of Bret Kavanaugh, the massacre at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, the monumental loss of life incurred from COVID-19 and a government that failed to act swiftly—I just went numb.

I did not cry that evening or even the next day. But in the weeks since I have caught myself being triggered, sometimes when reading pieces written by Ed Park or Jay Caspian Kang, other times seemingly at random, and breaking down into a sob in a quiet corner of our apartment where no one can see me. I take a few deep breaths, wipe the tears from my eyes, and then get on with the rest of my day.

In five years, Asian Americans have gone from being categorized as white adjacent to subhuman, diseased foreigners who are told we don’t belong here. I think about the anger I felt listening to NPR’s Code Switch podcast while the hosts questioned whether Asian Americans could be considered “OG people of color.” I think about the young Asian man on a NYC subway car being sprayed down with Febreze by another passenger at the beginning of the pandemic, an image that is forever seared into my mind. Febreze is something you use on furniture, bath mats, and smelly shoes—not human beings. I think about how in the days after the 2016 election my mom recalled that once when she was working at a Robinsons-May department store as a young woman, she saw an older man browsing and, in a friendly voice, asked whether she could help him. He promptly spit on her face and walked away. She was so stunned she didn’t even respond, which is not like my mom at all; she usually gets the last word!

Those who have been around long enough know that racism against Asian Americans, especially expressed through violence, has existed for as long as we have been in this country—I’m talking about hundreds of years of hostility and degradation. Although I knew the fact of anti-Asian hate to be objectively true based on stories I’d been told and my own research into Chinese American history, like many in my generation, this is the first time I am seeing it with my own eyes and that is an entirely different thing.

I worry for my family and friends who now walk out the door knowing they are an automatic target for anyone unhinged, emotionally distraught, or simply “having a bad day.” Being mixed, I don’t often get identified as Asian when I’m walking down the street, but I have avoided wearing a cap I own that is embroidered with the words 女强人, meaning strong woman, superwoman, badass. I used to wear that hat proudly. This suggests an unwanted metaphor. Stripped of my superpowers, I am ashamed to admit that I am now too scared to wear it out. I also feel shame knowing that I can choose not to draw attention, not to identify myself as Asian.

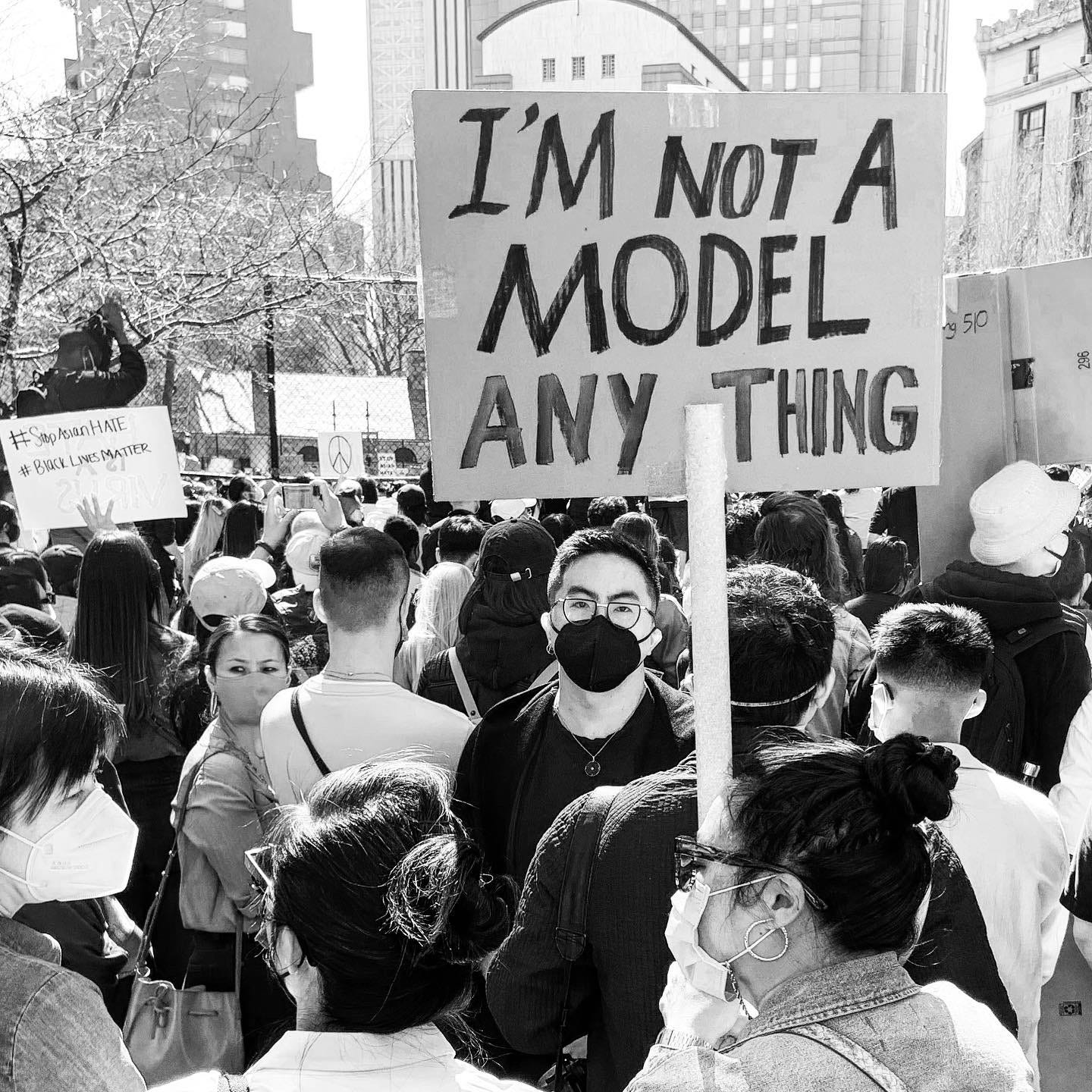

For too long the narrative around what it means to be Asian American has not been controlled by Asian Americans. We’ve been depicted as unfeeling automatons, degenerate opium addicts, evil masterminds, meek grinning buffoons, submissive China dolls, traitorous spies, vicious dragon ladies, worthless whores, perpetual foreigners, yellow peril incarnate. In the 1950s and 60s, a concerted effort was made to rebrand Asian Americans as “the model minority” who in contrast to other “minorities,” supposedly worked harder, kept quiet, didn’t complain, and magically excelled in spite of their circumstances. It was the ultimate gaslighting campaign. A way for white supremacy to maintain control by using Asian Americans as a racial wedge and justification for anti-Blackness.

I grew up in an Asian community and went to a high school where being an Asian American overachiever was the norm (I know this because I was one). My classmates and I accepted the model minority myth as truth because it explained the world we inhabited. There were few white kids or students of other races in any of my advanced math or honors English classes. If it looks true, it must be true, right?

I know better now. The model minority myth was a story we let others tell us about ourselves and we believed it. This affirms something I have long felt in my bones to be true: stories matter. So does who tells them.

This is not the essay I set out to write for this month’s newsletter, but it’s the one I needed to write. There is nothing my grief can do to bring back the 8 lives lost in Atlanta. What I can do is attend protest rallies and sign petitions to demand that our elected officials take action on anti-Asian hate as well as other issues that undermine solidarity among people of color and prop up white supremacy. I can honor the lives of the victims by giving to their families and supporting grassroots organizations like Red Canary Song and Asian American Legal Defense Fund and Education Fund. I can educate myself by reading books like Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings, watching PBS’s docuseries Asian Americans, and listening to podcasts like Time to Say Goodbye and Asian Not Asian. I can even school trolls on the internet until I can’t stomach the ignorance and hate anymore. Most of all, I can take control of the narrative about my own experiences and continue to write stories that are not being told in the mainstream media, whether they’re about the lives of Chinese restaurant workers in New York, my grandmother’s now demolished ancestral home in China, or the overlooked contribution of Asian laborers to the transcontinental railroad and the American West. I can write about Anna May Wong and the incredible life she led, never taking no for an answer even though the odds were stacked against her. (I promise we’ll get back to talking about her next month.)

I did not create this world, but I do believe that together we can change it. Maybe that’s a bit sentimental and kumbaya in a moment when so many of us are still hurting, but that is the story I tell myself in order to keep going. As the great Paul Robeson once sang, “I must keep fighting, until I’m dying.”

Say Their Names

Soon Chung Park

Hyun Jung Grant

Suncha Kim

Yong Yue

Xiaojie Tan

Daoyou Feng

Delaina Ashley Yaun

Paul Andre Michels