Digging Up Buried Treasure

books, family history & the cruel realities of 1930s Hollywood with Aimee Liu

As production on Not Your China Doll wraps up and the time until publication day ticks away, I’ve been looking back at the journey of writing the book and all the wonderful people—biographers, scholars, and super fans—I’ve met along the way. Many of these fellow travelers have become friends and allies whose curiosity and wisdom continues to inspire me. To highlight some of these personalities and their work, I’m introducing a regular interview segment to the newsletter. For the next several months, you can expect to receive these interviews in your inbox once a month in between regular essay dispatches.

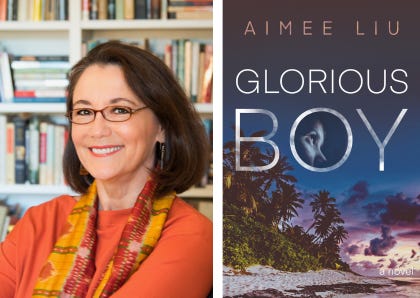

For my first guest, I’m excited to welcome Aimee Liu, author of the Substack Aimee Liu’s Legend & Lore, as well as numerous books. More below!

Aimee, it’s been so lovely getting to know you over the last year around our shared interests. You’ve made a career as a bestselling author and have written books, both fiction and nonfiction, that explore your family’s history, eating disorders, mixed Asian identity, and more. Your most recent novel, Glorious Boy, is a family saga set in the Andamans, an archipelago in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Myanmar. How do you generate your ideas? And when do you know you’re onto something that might be your next book?

Thanks Katie! I love that our writing connected us as online strangers, and now we’re in-person friends! It has been a real treat to share our nuggets of Asian Hollywood history, biracial Asian experiences, and publishing adventures.

As for my ideas, I have to say first that I am a slooooow writer when it comes to my own work. I also ghostwrite, and those projects are so much faster for me, probably because I get out of my own way. Ideas for my own books tend to come from personal confusion or uncontrollable curiosity. My nonfiction, starting with my memoir Solitaire, has mostly attempted to make sense of the seven years I spent starving myself before anyone had ever heard the word anorexia.

My first two novels, Face and Cloud Mountain, were attempts to make sense through fiction of the mysteries surrounding my father’s parents, a Chinese scholar revolutionary and an orphaned American pioneer, who met in San Francisco and decided to marry immediately after the 1906 Earthquake. I used those fiction projects to draw as much information as possible out of my frustratingly taciturn father. So much was still missing that I had to make up about 30% of the plot and virtually all of the emotional story, but I had a direct personal stake in those ideas. That stake continues to push me, which is why I’m now trying to write a memoir that gets closer to my father’s own experience as a first generation biracial Chinese-American with secretly divided political, cultural, and familial loyalties.

My third novel, Flash House, also started close to home, since my family lived in India for 2 years when I was little, and my father traveled all over Asia for the UN. He talked once about flying in a small prop plane over the Khyber Pass, and I asked my mother what she’d have done if he’d gone down. She loved India so much, I think we might have stayed there, but in any case, that What If question stayed with me and became the starting point of the novel.

The spark for Glorious Boy, in contrast, was part dream and part curiosity. Way back in 1998 I met an anthropologist’s wife who told me about these tropical islands off the coast of Burma where tribal people had lived outside the reach of “civilization” for 60,000 years—until the British set up a penal colony there for Indian Freedom Fighters in the late 1800s. After that, disease nearly decimated the tribes, but most of the islands are still largely wild and pristine. This introduction made me intensely curious about the Andaman Islands, but I had no story to set there until 2003, when I dreamt about a local girl who took a mute little white boy into hiding during an island evacuation, only to emerge to find the boy’s parents gone. That germ of a plot blossomed into a WWII story after I visited the Andamans in 2010 and learned that they were occupied by the Japanese and became the western front of the Pacific Theater—and all sorts of horrible and incredible things happened there after the British evacuated, leaving a few unlucky souls behind. If any of your readers are interested in a longer version of this genesis story, with pix of the Andamans, I’ve posted it on Substack here.

Bottom line, every book is different, but each is sparked by some personal connection that refuses to let go. If the fascination keeps growing over months and years, that’s when I know it’s a book.

We first connected on a piece I wrote about Asian Americans in Hollywood in the 1920s and 30s. It turned out that your father and aunt were both involved with the making of The Good Earth, the film that famously snubbed Anna May Wong’s bid for the lead female role. Could you tell us a little about your father’s experiences in Hollywood and the memoir project you’ve been working on related to that?

It's been so exciting to learn about all the overlap between my dad and Anna May Wong! When you sent me the clip of the two of them in Daughter of Shanghai, I was gobsmacked! I’d never seen it before! Dad spoke of Anna May Wong with reverence, but the only part of his acting career that he ever discussed was The Good Earth. He said he was cast and shot as one of the brothers in an opening scene, but his role wound up on the cutting room floor. He also worked as a technical advisor, providing background information on China to screenwriter Frances Marion, who also wound up being uncredited on the film. There was a lot of un-crediting happening with that film, much of it sexist, racist, and just plain inexcusable. The practice of yellowface, or white actors being made up to play Asians, began earlier, but The Good Earth was the first time it was used to prevent Asian actors from starring in a truly major motion picture. And it was especially egregious because Pearl Buck had stipulated when she sold the rights to her novel that Asians should play the leading roles, and producer Irving Thalberg agreed. But they were later overruled, for fear that Asian names on the marquee would be bad for box office returns. Anna May Wong and my aunt Lotus Liu (initially cast for the role of Lotus after Wong declined it), even more than my father, were casualties of this reversal.

My father’s reluctance to discuss his 1935-1938 Hollywood career was one of the catalysts for my new memoir project. My brother and I could not figure out why he wouldn’t regale us with stories about playing the groom in Waikiki Wedding alongside Bing Crosby, or the handsome Willy Fu in Shadow of Chinatown with Bela Lugosi. We thought it must have been a kick for him. But once I started researching the racism and politics of Hollywood and America in that era, I began to understand just how much shame and betrayal my father associated with those experiences.

Dad later went on to a long and rewarding career with the United Nations, and he never wanted to look back on his past. Unfortunately, along with his Hollywood stories he also buried a great many other significant memories, of his “Eurasian” childhood in Shanghai, his work as a photojournalist in wartime China and as a correspondent for the Nationalist government, of his persecution for decades by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, and of his guilt over leaving his father to die in China after the Communist takeover. I knew very little about any of this until my father himself died in 2007, leaving countless boxes of documents, letters, photographs, and other artifacts that told or hinted at the stories he had kept to himself for most of his life. These are like pieces of a massive 3-D jigsaw puzzle that I’ve been struggling now for 16 years to assemble in some form as a memoir. I’ve been posting some of these pieces as essays on Medium and in the Chinese-American Legacy section of my Substack newsletter, and I do think the book will ultimately take the form of linked essays. But who knows when I’ll finish?!

Wow. Your father was being tracked by the FBI? That sounds intense. I hope you do finish the memoir, at least for my sake! Because I’m dying to read it. These types of histories fascinate me.

Given the sea change that’s taken place since Crazy Rich Asians came out in 2018, do you think your father and aunt would be excited by the progress that’s been made today for Asian American representation on screen?

I think my aunt would be delighted! She was a larger-than-life character whose spirit would have been right at home in Crazy Rich Asians, even though she stopped identifying as Chinese as soon as her Hollywood career ended, around 1940. But she’d have thought these new movies were a hoot, and I think she’d have cheered for Asians getting the acclaim she was denied.

I’m not sure what my father would have thought of the latest Asian hits. After the fact, I think he was embarrassed by his naïveté in thinking he could ever have succeeded in Hollywood. And realistically, he was too much of an introvert to have succeeded onstage, even if he’d had the chance. Also, he was so restrained that I think he’d be mortified by the loud, proud, over-the-top portraits of Asian characters in vehicles like Crazy Rich Asians and Beef. The early Ang Lee films like Eat Drink Man Woman were more his speed. But as far as others having the chance he was denied, I know he’d have heartily approved.

Sometimes as a writer you don’t really know what you’re interested in until you start writing. What do you think drives your interest in excavating and recovering these types of personal and family histories?

For me, it’s like digging up buried treasure. What keeps me interested is the mystery surrounding my Chinese grandfather and ancestors. I knew my white maternal grandparents, and everything my mother told me about her midwestern grandparents and countless cousins seemed so familiar, none of it piqued my curiosity. But my Chinese grandfather was born and raised in Imperial China—another universe entirely! All my life I’ve been unable to fathom how so much could change within our family in a single generation, and yet no one ever talked about these changes or the bridges that were initially built to bring the Asian and American sides of my heritage together—and then burned to push them apart. That irreconcilable conflict between East and West that physically lives inside me—that’s what drives my unquenchable interest, I think.

Also, within all that, I feel tremendous sympathy and admiration for my Chinese grandfather Liu Chengyu, a poet, historian, scholar, and teacher who was the only other writer besides me in our family. I write these stories to honor his legacy because, now that my father is gone, no one else in my family seems to care about his life, his work, or the fact that his American wife and children quasi-knowingly abandoned him in the run up to 1949.

You can follow Aimee on her Substack and find her latest book Glorious Boy here.

Absolutely fascinating. Thank you for a great interview. With photos!