Background Artist

longevity, Tyrus Wong & the power of art with Karen Fang

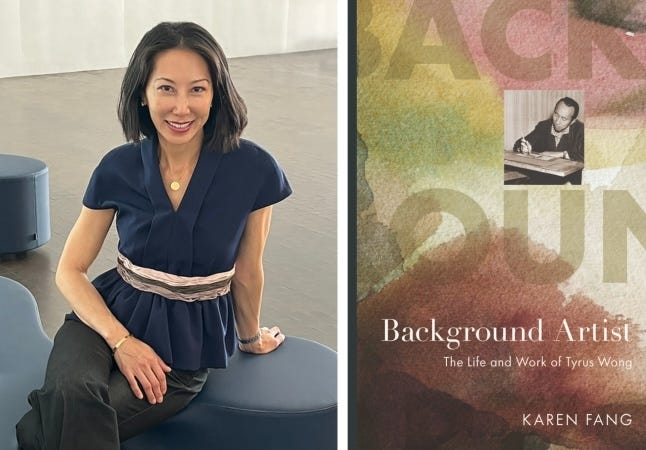

Karen Fang is a film scholar and visual culture critic who writes and speaks for museums and film festivals around the world—and my guest for this month’s interview. You may recall seeing her name mentioned a while back, when she and I and William Gow did a virtual event together on Chinese Americans in classic Hollywood. Karen has previously written books about Hong Kong cinema and nineteenth-century British interest in exotic objects, and her forthcoming book, Background Artist: The Life and Work of Tyrus Wong, is a much needed addition to the annals of Chinese American history.

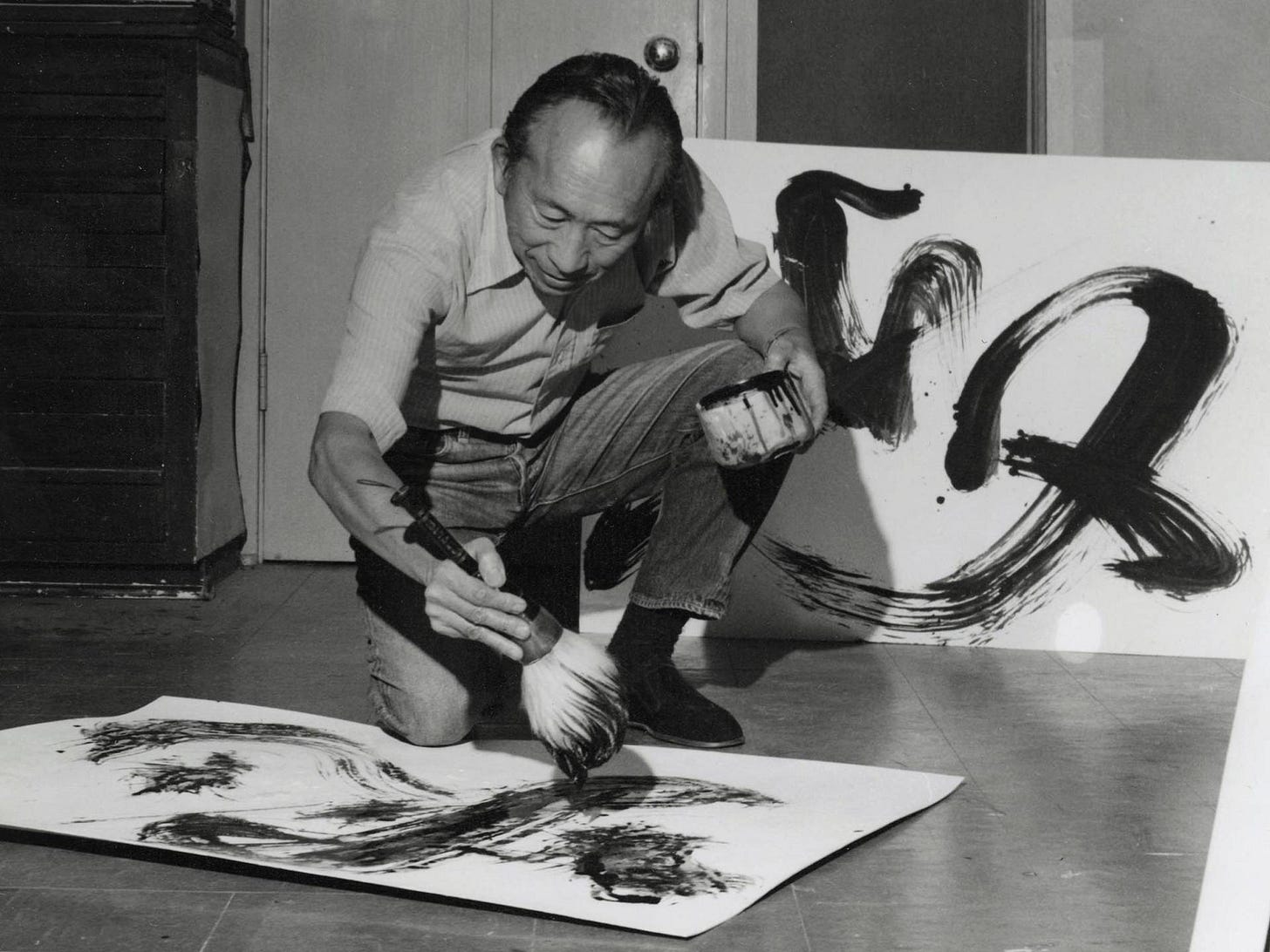

Tyrus Wong is best known for his work on Disney’s Bambi, creating the background art that inspired the look and feel of the film, which many still hold dear today. It wasn’t until years later, however, that Tyrus was fully acknowledged for this contribution. And yet, his time at Disney was merely a blip on his long, varied career, which Karen skillfully documents in her book.

Tyrus was also friends with Anna May Wong, dating back to the late 1930s when she hung out at Dragon’s Den with Eddy See and company. Like Anna May, Tyrus faced many challenges as an immigrant and Chinese American. In spite of the setbacks he experienced, he always found a way to continue practicing his art, often with spectacular results, especially in the way that he was able to fuse Chinese artistic traditions with Western ones. The similarities between Tyrus and Anna May’s careers are striking.

Karen, it’s been so fun getting to know you over the past year and to collaborate on several events with William Gow and Susan Blumberg-Kason. There is so much overlap between our interests. How did you first get interested in Tyrus Wong? And what made you decide to write a biography of him?

I think, like many people, I became very interested in Tyrus in the months and years after his passing in late 2016. A documentary film about him had come out the previous year, and there had been extensive coverage when Tyrus passed in late December 2016—two days before the New Year, and after weeks of terrible anti-immigrant feeling that had been stirred up during the 2016 election. By 2018, when immigrant children were being separated from their parents because of U.S. policy, I was struck by the sad similarities of his experience from nearly a century earlier.

Something a little different which added to my growing interest in Tyrus was my own work as a film scholar and an Asian American who often writes about the unexpected intersections of global visual culture. Because of motion capture and other forms of digital effects, animation is more important a part of cinema than ever before. And long before Everything, Everywhere All At Once became the most awarded Oscar film ever, the #OscarsSoWhite critique was arguing for recognition and representation of ethnic Asians in Hollywood. I realized that I’d been running across Tyrus’s name with increasing frequency, but the extraordinary depth of his career deserved thorough study.

I had the pleasure of reading an early copy of your book and one of the things I was struck by were the difficulties Tyrus had navigating the U.S. immigration system and its discriminatory treatment of Chinese under the Chinese Exclusion Act. Even though I studied this law and its consequences, especially as it affected Anna May Wong, it seemed to have a much more dramatic impact on Tyrus’s life. Could you tell us about the time he went down to Tijuana to sketch with his art school classmates and what happened as a result?

Yes, Tyrus’s unintended month in Tijuana is such a telling example of the precariousness of ethnic Asians during the Exclusion era. In fall 1931 Tyrus was a popular and much admired student at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, which he attended on scholarship. Artists often go on plein air excursions to paint and sketch on location, and that day he and some other artist friends had driven south to Tijuana, Mexico for the day to sketch. As a Chinese immigrant, Tyrus was required by U.S. law to carry with him at all times proof of his “alien” registration, showing that he was legally allowed to be in the U.S., but because Tyrus had never even left California since his arrival in the U.S. ten years earlier, he probably forgot about that requirement. When he and his friends tried to reenter the U.S. after a few hours of sketching, Tyrus was refused re-entry. He ended up spending a month stranded in Tijuana, while his friends, father, and art school administration worked on the other side of the border to help him return.

As creatives Tyrus and Anna May are similar in that their travels were colored by their professional identity, and another thing that is striking about both their experiences is that under Exclusion the regulations on ethnic Chinese movement across the U.S. border were so strict that even a native-born American citizen like Anna May could be refused reentry, as occurred to Tyrus. I was surprised to learn from you that Anna May had a similar experience on the Canadian border, when she was returning from a film shoot. Anna May was a citizen, but because Exclusion law required U.S. Border Patrol to view all ethnic Asians as possible foreigners, she was also subject to interrogation, and should have applied for reentry papers prior to her U.S. departure.

Studio connections probably helped Anna May get through without delay, but even Tyrus’s status as an art student eased a predicament that could have ended much worse. In my book, I talk about the irony that Western culture has long admired Asian art, even while American history has explicitly marginalized ethnic Asians. At the border in Tijuana, U.S. immigration officials might have seen him only as another unwanted Chinese migrant, but Tyrus had connections that few of his Chinatown peers had. With the help of Y.C. Hong, a trailblazing immigration attorney who ultimately helped more than 7,000 hopefuls apply for American entry, Tyrus eventually was readmitted. Only after re-entering the U.S. would Tyrus be able to continue on his extraordinary artistic journey.

Was it challenging writing a biography of someone who lived to be 106 years old? Anna May Wong died at 56 but she lived a packed life, which was hard for me to contain in 120,000 words. I can only imagine how hard it would have been with a subject who lived nearly twice as long! How did you approach the research and writing process?

Surprisingly, no!—Tyrus’s long life was never a challenge to write about; rather, it was always a boundless well of inspiration.

Obviously, there are definitely practical challenges to writing about a centenarian: publishers get nervous about long books, and as a writer I had to choose what stories to explore and what could be condensed. The sheer depth of things that Tyrus had lived through and done is a huge part of his story, so as a researcher I couldn’t get lost in rabbit holes and always needed to keep an eye on the big picture.

The big picture, I knew, was Tyrus’s incredible legacy in American visual culture, despite prejudice and historical challenges. It also is his inimitable personality, which always chose beauty and humor as forms of resilience. The COVID-19 pandemic broke out while I was deep in research, and although rising anti-Asian hate made me scared for myself and my family. I knew that Tyrus and thousands of other Chinese and Asian Americans had survived far worse. I turned 50 while writing this book, a big moment for me both personally and professionally—and yet I still haven’t lived half as long as Tyrus!

Did you glean any insights into Tyrus and Anna May’s friendship from your research? I wonder if you could also tell us a bit about Dragon’s Den, which was a favorite hangout where they likely saw each other often.

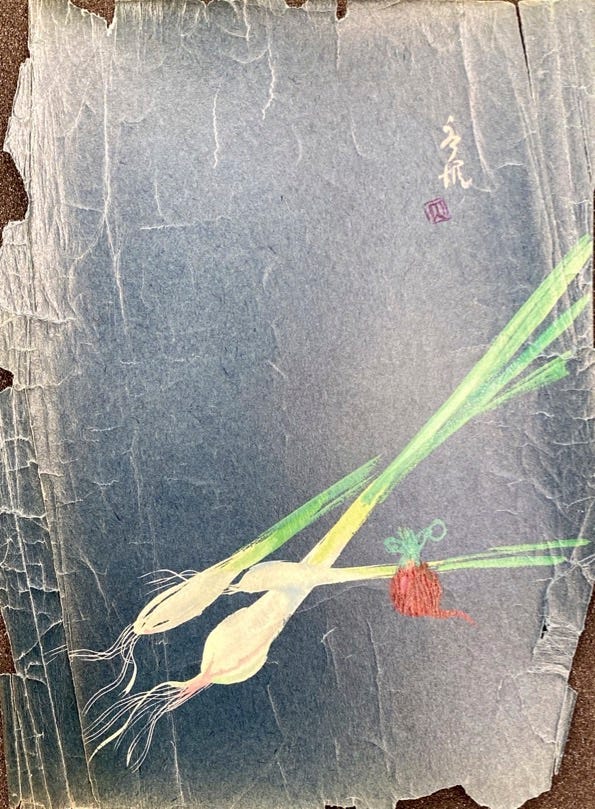

Dragon’s Den was a chic and trendy Chinese restaurant in Los Angeles’s “Old” Chinatown, which opened in 1935. The restaurant was started by brother and sister, Eddy and Florence See, members of the prominent biracial See family, who were some of the first major importers of Chinese antiques and curios. Because of the family’s interest in art and aesthetics, Dragon’s Den boasted a uniquely creative milieu, in which Hollywood types were just as common as Chinatown residents. Tyrus worked there as a waiter, fresh from art school and still growing his reputation as a fine artist, but his centrality within Los Angeles’s creative community was already evident in the important role he played in shaping Dragon’s Den look and experience. Tyrus helped decorate the restaurant’s interior and exterior murals, and designed most of Dragon’s Den’s branding. Most significantly, Tyrus personally painted dozens of unique menu covers, so that every diner sitting down to eat there had a personal encounter with Chinese-style art.

If you’ve read novelist Lisa See’s bestselling family memoir, On Gold Mountain, Dragon’s Den is already familiar for its multigenerational glimpse into Chinese American history. In my book, however, I also want readers to see Dragon’s Den as an important space in Hollywood history, and in American visual culture more generally. Film buffs all know about famous Hollywood restaurants like the Brown Derby and the Polo Lounge, but with the occasional exception of stars like Anna May Wong, those places were predominately white spaces, and the artistic-creative aura they cultivated was largely limited to the Hollywood industry.

Dragon’s Den, by contrast, was a far more eclectic and egalitarian space, which brought Hollywood to Chinatown, and where fine art painters and commercial designers mingled with film studio elite. At the time that Tyrus and Anna May first got to know each other at Dragon’s Den, he was at a much earlier stage in his career than the Hollywood star. Yet they are typical of the inclusive, creatively engaged community surrounding Dragon’s Den, whose impact continues in their enduring legacy, as well as subsequent generations like Lisa See.

Although most people today know Tyrus for his visionary work on Disney’s Bambi, he started as a fine artist and later had a successful career as a commercial artist, creating art for greeting cards. In fact, I had no idea that he designed the logo for Phoenix Bakery, which is a beloved institution of L.A.’s Chinatown—and a place my family has been going to for sugar butterflies and strawberry whipped cream cakes since before I was born. What are some of your favorite pieces that he created across his diverse career?

With an artist with as long, prolific, and diverse a career as Tyrus’s, it is impossible to pick a favorite. In just the greeting card part of his career, for example, Tyrus created about 500 unique designs! Because he worked in so many different media and fields, there are also collectors and curators—like Disney fans or ceramics connoisseurs—who know Tyrus primarily through one context and may not be aware of other parts of his artistic legacy.

One of the things that I hope Background Artist does is establish the historic importance of Tyrus’s “Chinese Jesus” painting, which is a full-length Christ portrait with Sinicized features that Tyrus painted for a Chinatown church in 1936. The painting was thought lost for years, but since its rediscovery (itself another episode in Tyrus’s perpetually improbable life!), Chinese Jesus is increasingly recognized as a landmark painting, unique in American art history.

I’m lucky to have seen probably more of Tyrus’s artistic corpus than almost anyone. Along with private and ephemeral works like his art school sketches and personal correspondence, I’ve also examined movie illustrations that remain studio and corporate property. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t have a favorite Christmas card, a cherished Bambi sketch, or a movie illustration that I can’t forget. But when I think back on all the beauty, inventiveness, and personality evident across all of Tyrus’s work, what I admire most is the sheer limitlessness of his imagination. The life force that helped him live to 106 shines through all of his art.

P.S. for more on Sing Sing, the mascot logo that Tyrus designed for Phoenix Bakery, look for my article on the topic in the forthcoming Five Chinatowns volume we’re both in!

What do you hope readers take away from Tyrus Wong’s story?

Empathy, Community, and Creativity. Art works by provoking emotions, and its capacity to stir up feeling can be a powerful way to get us thinking about our relationship to it and each other. When I first started researching Tyrus, I thought his story was primarily a project of recovery and pathos—showing what he had endured, and finally giving him credit for all he had done. But once you spend time with his history, you understand that Tyrus never let the past dampen the present. It’s this infectious, irresistible joy in creativity that Tyrus shared with so many other artists and creatives, and which drew many more to him, whether it was collectors of his art or the passerby who saw him flying kites on Santa Monica Beach.

I hope that anyone interested in Tyrus will also think more about America’s complicated history with ethnic Asians. But whether or not that thought is conscious, I’m sure that Tyrus continues to make the world better—not only through his art, but also because his story reminds us of the power of creativity, and the community that creativity fosters.

Karen Fang’s biography of Tyrus Wong, Background Artist, is available for purchase here. For reviews, events and other information about the book, visit her website. P.S. The audiobook for Background Artist will be available in November and is read by Caroline McLaughlin, the same narrator of Not Your China Doll!

Wonderfully interwoven stories and themes. Will share.