The China Doll Brigade Sets Sail

that time Bob Ripley threw a party on a Chinese junk and invited Anna May Wong

Several weeks ago, as I sat in a screening room at the UCLA TV and Film archives in Powell Library, waiting for a video to begin playing, something peculiar happened: the wrong clip played. Not once, but twice. I’d searched the UCLA catalog in preparation for my visit and requested a number of the items that came up. This item in particular was vaguely titled “Bob Ripley's party—New York City” and dated August 10, 1946. I scarcely knew what that meant, but if it was related to Anna May Wong in some way, I wanted to see it.

It took some digging to queue up the correct clip since it was on a VHS with multiple newsreel clips from the 1940s. After the false starts—clips of WWII events in Germany and China, and a track cycling race—the student working at the desk asked me what I was looking for. Darned if I knew. No one at the library, it seemed, had any idea either. So I told her what I knew: the clip was called “Bob Ripley’s party” and had something to do with movie actress Anna May Wong. She checked the tape again. “Was the actress Asian?” she asked. I nodded. “Okay, I think this should be it.”

I returned to my screening room and waited for the video to begin. First, a few establishing shots appeared on the television of people walking down a stone pathway lined with Chinese lanterns, heading towards a waiting boat. In quick succession, a flurry of shots flashed across the screen: a man in a captain’s hat flanked by two smiling Asian beauties in tight-fitting cheongsams, their faces made up with lipstick and pencil-thin eyebrows, foreheads adorned with straight black bangs; more Asian women appear aboard a Chinese junk, wearing various forms of Chinese dress, from modern designs with shoulder pads to old school culottes, some sporting shades, flowers in their hair, or 40s-style pompadours; the women wave-laugh-smile for the camera; the man in the captain’s getup, presumably Bob Ripley, is notably not steering the boat; instead, he grins like a schoolboy at his good fortune to be surrounded by such glamorous company.

In the four plus years I’ve spent researching Anna May Wong’s life, this was quite possibly the strangest thing I’d ever seen. What exactly was it? An Anna May Wong-lookalike party? Was Anna May Wong even present, I wondered? Then I saw her. An older Anna May, looking quite ordinary sitting among the other women and smoking a cigarette, as if she was waiting in line at a casting call for China dolls. On the boat, she sits among her duplicates and watches a game of mahjong. There’s a Chinese man in a black silk shirt and cap with a cigar hanging out of his mouth, as well as a white man similarly dressed in a light-colored silk shirt, his cap slightly askew. In a later shot, AMW chats with Bob Ripley, the man in the captain’s hat, and they seem to share a laugh at some joke.

The footage is composed of four clapboard takes, lasting about four minutes, with no sound or voice over to hint at what kind of occasion it captures. I rewound and replayed the tape half a dozen times, taking notes and trying to make sense of it. Viewing after viewing, I couldn’t help but shake my head and laugh at the sheer absurdity of it. Since then, I’ve slowly pieced together the facts. Of course, all the answers were in UCLA’s online catalog description if I’d only bothered to look. But what fun would that be for a researcher-cum-amateur-sleuth?

The name Bob Ripley means little to my generation, but you don’t have to look far to realize Bob Ripley is that of Ripley’s Believe It or Not! fame. Boomers remember him as the man behind the Believe It or Not cartoons that used to appear in newspapers around the country. Millennials are more apt to call to mind his cringeworthy “odditoriums” filled with pithy tales from his world travels and the souvenirs he brought home with him—things that were once considered bizarre curiosities like Buddhist temples, Aztec masks, and shrunken heads. Having visited the Ripley’s Believe It or Not! at the Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco on more than one occasion, I often wondered what kind of a man would amass such a collection of sordid and phony knickknacks? (Following one visit, I laughed maniacally for days at the mere thought of Ripley’s tale of the Lighthouse Man.)

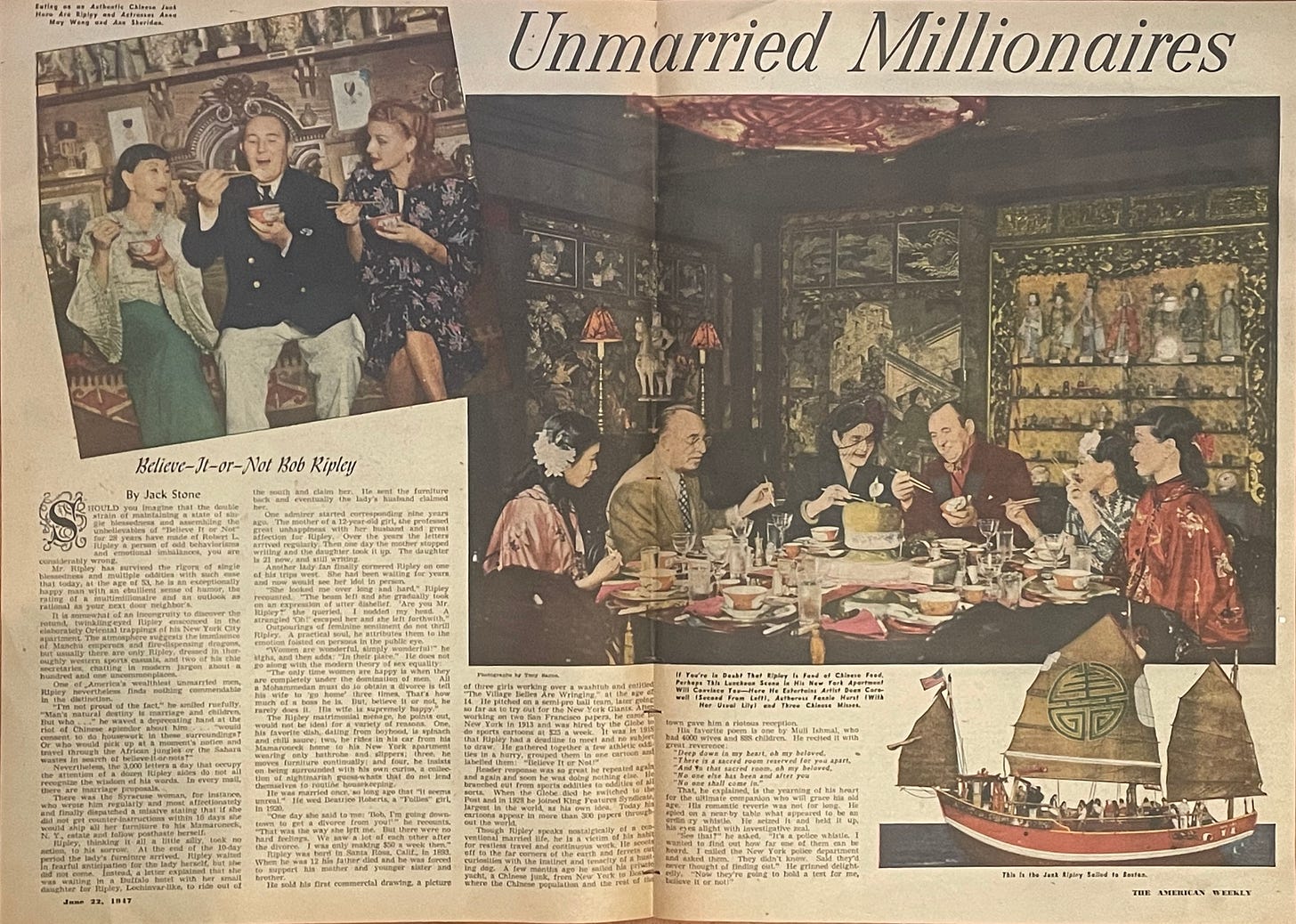

Robert Leroy Ripley got his start as an illustrator and jokester. After his dad died suddenly, he looked for ways to support his mother and siblings. He sold his first drawing at age 14, which pictured three girls washing clothes over a washtub under the title “The Village Belles Are Wringing.” Later, to meet a deadline, he pulled together a few factual oddities under the heading “Believe It or Not!” Reader response was so great that he kept the series going. By the 1940s, the Believe It or Not franchise had grown into an empire: the daily cartoon was syndicated in more than 300 newspapers; books, a live radio show, and screen shorts were released; and numerous odditoriums were erected to display the unusual wares Ripley, sometimes called the “modern Marco Polo,” brought back from his expeditions. When American Weekly profiled him in a 1947 article headlined “Unmarried Millionaires,” he was rumored to be earning half a million dollars a year.

With the spoils of his white male colonial gaze, Ripley built himself a mansion on an island he christened Bion—an acronym for Believe It or Not—off of Mamaroneck, New York. His home, naturally, was crammed with outlandish junk valued at $3 million, including life-size bronze Chinese warriors, a 10-foot high Yucatan god glowers (whatever that is), Ali Baba oil jars, the flags of 197 countries, a mouse clock, and a “low, beamed ceiling with long poles dangling dozens and dozens of tinkling camel bells, elephant bells, cow bells.” When Miss Worth, Ripley’s estate manager, was asked what she thought of all this stuff, she replied sensibly: “The thing I think about most, when looking at the things, is not wonderment but the trouble of keeping them clean!”

Of all the places Ripley had visited, the Orient held a special place in his heart. In addition to a Chinese butler, he was customarily joined by a Chinese lady named Ming Jung, described as his “secretary-companion-cook.” (She can be seen in the footage from the Mon Lei and pops up in several newspaper articles on Bob Ripley, including one in which she advises the reporter what to order for dim sum at New York’s Nom Wah Tea Parlor.)

Which is why when Ripley saw the Mon Lei (萬里), a stylized Chinese junk, idling in the Baltimore Harbor, he knew he had to have it. Like many of his possessions, the boat came with its own storied history. The Mon Lei, whose name means “far away” or literally “10,000 miles,” first surfaced off the coast of California in 1939 where it was to be exhibited at the Chinese village at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco. According to then-owner Rene Crosby Monteith, out of six Chinese junks built in Hong Kong for the exposition, the Mon Lei was the only vessel to successfully navigate across the Pacific Ocean, guided by Monteith and his crew in a “stormy, 37-day crossing.”

Monteith initially claimed he purchased the boat from a wealthy Chinese merchant, but that story later morphed into a tale about getting it on the cheap from a once powerful warlord now under the thumb of the Japanese occupation. In truth, Monteith, purportedly the son of an American who had once worked in the Harbour Master’s Office, hired Wo Hop Junk and Boat Construction in Hong Kong to build a three-masted, 50-foot boat in the Fujianese style. Completed in the summer of 1939, the Mon Lei was not launched into the Pacific, but instead loaded onto a cargo ship in Hong Kong headed for Long Beach, California. The resulting boat looked very much like an American’s idea of a Chinese junk, not quite authentic. The Mon Lei’s fantastical quality only intensified when Bob Ripley took ownership of it.

Ripley had the boat completely refurbished and lacquered red, plus white trim and details in bright yellow and blue painted on. Its three masts were outfitted with webbed sails like the kind seen in China. On either side of the prow, a pair of large black and white eye were added, for as Anna May once wrote, “so that the boat could see its way.” Ripley installed a 165 horsepower diesel engine, removed the lifting rudder and tiller, and the boat was soon sailing as fast as 18 knots an hour. Most important, he gave it a distinct Ripley flourish by decorating the cabin and deck with pieces from his own collection, such as oriental rugs, a prayer wheel, and a Happy Buddha whose midsection was noticeably worn from the number of guests rubbing his belly for luck. Everywhere the Mon Lei sailed, to Connecticut and Boston and as far south as Florida, it caused a commotion. Crowds of people mobbed the nearest dock, hoping to get a better look at the unusual boat and maybe even a joy ride.

By the summer of 1946, the Mon Lei was in tip top shape and ready to return to sea. It seems Ripley decided to launch the boat from his home in Mamaroneck with a little publicity stunt at the beginning of August. What better way to throw a party on a Chinese junk than with a bunch of theme-appropriate guests? Enter Anna May Wong and her gaggle of lookalikes.

Just Ripley’s luck, AMW was in town that August on one of her yearly visits to NYC to see friends like Fania Marinoff and Carl Van Vechten. How Ripley’s invitation reached her is anyone’s guess, but celebrities, then and now, generally run in the same circles. For instance, movie actress Ann Sheridan also makes a cameo in the newsreel footage, along with journalist and humorist “Bugs” Baer (the white guy in Chinese robes and cap).

As for the Asian guests on board, they represent a who’s who of New York’s Chinatown. The man in the black silk shirt is none other than Shavey Lee, the self-proclaimed “Mayor of Chinatown,” a flamboyant personality, power broker, and restaurateur well-known in the Chinese quarter. Lee, whose nickname derived from the fact that his father used to shave his head to keep him cool in the summertime, counted New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia among his good friends.

What’s more, the legion of ladies aren’t just any China dolls, they are the China dolls—the newly minted performers at Tom Ball’s China Doll nightclub on 51st Street and Broadway. Billed as “New York’s only all-oriental night club,” China Doll was a supper club where stereotypes of Asian women were served up as exotic fare. The venue followed in the tradition of Harlem nightclubs like the Plantation and Cotton Club, where Black entertainers performed mainly for white audiences. In fact, these showgirls were part of a growing number of acts featuring dazzling Asian American singers, dancers, and stage personalities that performed on the Chop Suey Circuit. (Lisa See writes about this phenomenon in her novel China Dolls, as does Arthur Dong in his nonfiction book and documentary Forbidden City.) Mary Mon Toy and Jessie Tai Sing, fixtures of the China Doll nightclub, are among the faces I spotted aboard the Mon Lei.

It’s fitting, then, that I assumed these women were mimicking Anna May Wong. Because they were, in a way. AMW was the prototypical China doll, who effortlessly entranced white men and fell in love with them at her own peril. In countless films, she glided lithely across the stage in extravagant, often skimpy, showgirl attire. She was the woman who made the mold, for better or worse, and set expectations for all the Asian women to come after her.

AMW was 41 when this memorable outing on the Mon Lei took place, and though hardly old by modern standards, the wear and tear of hard living—drinking, smoking, bouncing nonstop from one corner of the globe to another making films and personal appearances—had begun to show on her face. In this moment, set against the backdrop of so many vital, youthful beauties, she was decidedly no longer the China doll.

I find it difficult to look at images of beautiful women in their later years, especially when it comes to screen sirens. Strange to say this aloud, but it’s always a shock, like a sucker punch to the stomach, to see the sagging skin and harsh lines where soft, easy beauty once prevailed. To value someone so superficially feels wrong, and yet it’s hard to shake that crestfallen feeling. It’s like being forced to acknowledge the world is now a little less than what it was. But why should I feel bad when it was AMW’s career that suffered?

AMW couldn’t convincingly play the exotic vixen anymore. Aside from the pair of poverty row propaganda films she made during the war years, the screen roles available to her dried up in the 1940s. It wasn’t until the mid-1950s that she finally recovered from her depressed state of mind and a serious bout in the hospital due to cirrhosis. She discovered that she enjoyed the new kinds of parts she was fetching on television.

“After the war, I did nothing for about five years,” AMW explained to Hollywood reporter Bob Thomas in a 1959 interview. “I had come to that transition when I had to change from leading roles to character parts. I think I have made it now. I have been doing television shows—even Westerns like ‘Wyatt Earp’—and I find character roles are more fun.”

Maybe she was also relieved that she no longer had to play the China doll or be someone else’s sex object.

In 1946, her profile remained in a sunken state, squarely out of the limelight. The media barely even noticed her at Bob Ripley’s party, and it’s likely the footage meant for the newsreels never ran since no voiceover accompanies the clip. Aside from The American Weekly, no other publication that I can find mentions AMW’s presence on the Mon Lei.

But if you look closely, you’ll see that Anna May Wong is there, hidden in plain sight—sandwiched between “Bugs” Baer on her right and one of the China dolls on her left (the woman who looks like Mary Mon Toy). She’s leaning over Bugs and pointing at the tile he should put down next if he wants to win at mahjong. Anna May Wong isn’t in the game, but she still knows how to play it.

An Update from the Book Trenches

After writing around the clock through the first week of August, I finally dusted off my hands and turned in the first draft of my book! Whew. This summer was a feverishly productive time for me. Kicking off in June with Jami Attenberg’s #1000wordsofsummer challenge, I wrote a whopping 48,234 words towards the book over the last three months—more than a third of the full manuscript, which clocked in at about 120,000 words. Thank god for editors!

August was dedicated to visiting several different archives in California, including the UCLA Film and Television Archive, the Paul Kendel Fonoroff Collection for Chinese Film Studies at UC Berkeley, the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, and Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. I spent the majority of my time at the latter, driving daily through the L.A. traffic to Beverly Hills, where I got to know the library staff fairly well. They made me feel like I was one of the gang, and I warned them that I’ll likely be back for another visit soon.

So what’s next? While my manuscript is with my editor, I’m focused on organizing the new research material I’ve collected over the last month and making notes on all the revisions I’ll need to make when the manuscript comes back to me. Also in the works are a few other short AMW-related pieces, including an article in Vanity Fair online about AMW’s imminent unveiling on U.S. quarters this fall. Keep an eye out for the article when it runs in VF at the beginning of October. Until then, Happy Mid-Autumn Festival! 但愿人长久,千里共婵娟!

Great history. You are a good sleuth.

Wow! Fascinating story! Well done!