Something that has always puzzled me is how a woman so constantly and beautifully photographed could ever drop out of the limelight. Even if you don’t know her name, a vast catalogue of her pictures is only a Google search away. However far down I go into the rabbit hole, there are always new images of Anna May Wong waiting to be discovered. In fact, Anna May Wong continues to command a dedicated fan base that scours the four corners of the internet and eBay listings looking for Hollywood gold.

In AMW’s youth, artists practically lined up to arrange a sitting with her. The list of famous photographers who captured her image for the ages and enshrined it in film, pen and ink, and paint is long and seemingly never ending. The British National Portrait Gallery is a treasure trove full of pictures taken of AMW while she was abroad in Europe.

When I started this newsletter in 2021, I wrote about my favorite photograph of AMW taken by Otto Dyar. This month I thought it would be fun to take a romp through a dozen or so equally enchanting portraits of Anna May Wong.

If this issue appears truncated in your email, read the full post on the web here.

Anna May Wong arrived in London in the summer of 1928 to much fanfare. Her first European film, Song, was soon to release in Germany and the entire Continent seemed to be buzzing about her extraordinary charm and talent. Paul Tanqueray, a young London photographer, was likely one of the earliest to photograph AMW after she settled into the London social scene. His stunning portrait of her lying back lithely on a black velvet divan, with crisp white lilies draped across her chest, is simply divine. No wonder it was selected to be shown at the London Salon of Photography’s exclusive annual exhibition in 1929. That year AMW featured in three of the images exhibited—two were by Tanqueray.

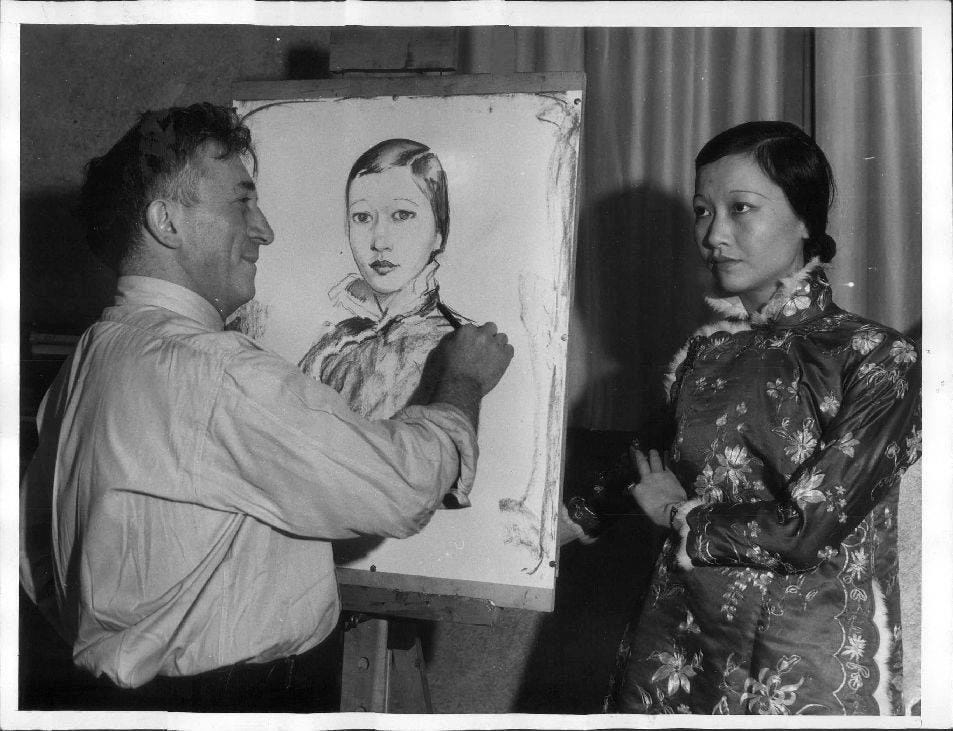

Willy Pogany was a Hungarian artist best known for his illustrations of children’s books, but he also worked in motion pictures. Pogany, for example, illustrated the dust jacket for the movie tie-in edition of The Thief of Bagdad (1924) and he was also the set designer for The Devil Dancer (1927) in which AMW had a small role. Pogany and AMW were friends. She invited him to her dinners in Chinatown. When he moved into a new studio in Hollywood, AMW was the first study he sketched. Charlie Chaplin attended a tea at Pogany’s home one afternoon and was impressed with his portraits of AMW. Los Angeles Times columnist Mollie Merrick gushed that Pogany’s “canvas of Anna May Wong is one of the most exquisite conceptions in oil that I have ever seen.”

Dora Kallmus, or Madame d’Ora, as she was more popularly known, established her first photo studio in Vienna, where she was born, and broke a lot of firsts in Austria as a female photographer at the turn of the 19th century. By 1925, she had moved her studio to Paris. According to a pamphlet from the Millesgården Museum in Sweden, d’Ora’s Paris studio was “a fashionable meeting place” where “she turned her lens on aristocrats and artists, variety artists, and trailblazers.” It was in Paris that she photographed AMW, who was likely there on a vacation between films. Madame d’Ora’s other famous sitters included Josephine Baker, Colette, Anna Pavlova, Gustav Klimt, and Anita Berber. (Special thanks to Joanne Knight for sending me the Millesgården pamphlet.)

George Cannons, professionally known as Cannons of Hollywood, was a British photographer who worked in Hollywood following World War I. He started out by making portraits of Mack Sennett’s Bathing Beauties and gained a reputation for being “the English photographer of Hollywood.” This hypnotic portrait of AMW dressed in a tuxedo and top hat, a cane clasped in either hand as she balances a cigarette between her fingers, is a rare and unusual shot. It’s AMW at her most androgynous. The picture was featured in Bystander magazine in February 1933 to publicize Cannons’ newly opened London studio, but in a way, it was also early promotion for the vaudeville show AMW would launch in a few months at the Embassy in London. For one of her numbers, she appeared in her tuxedo.

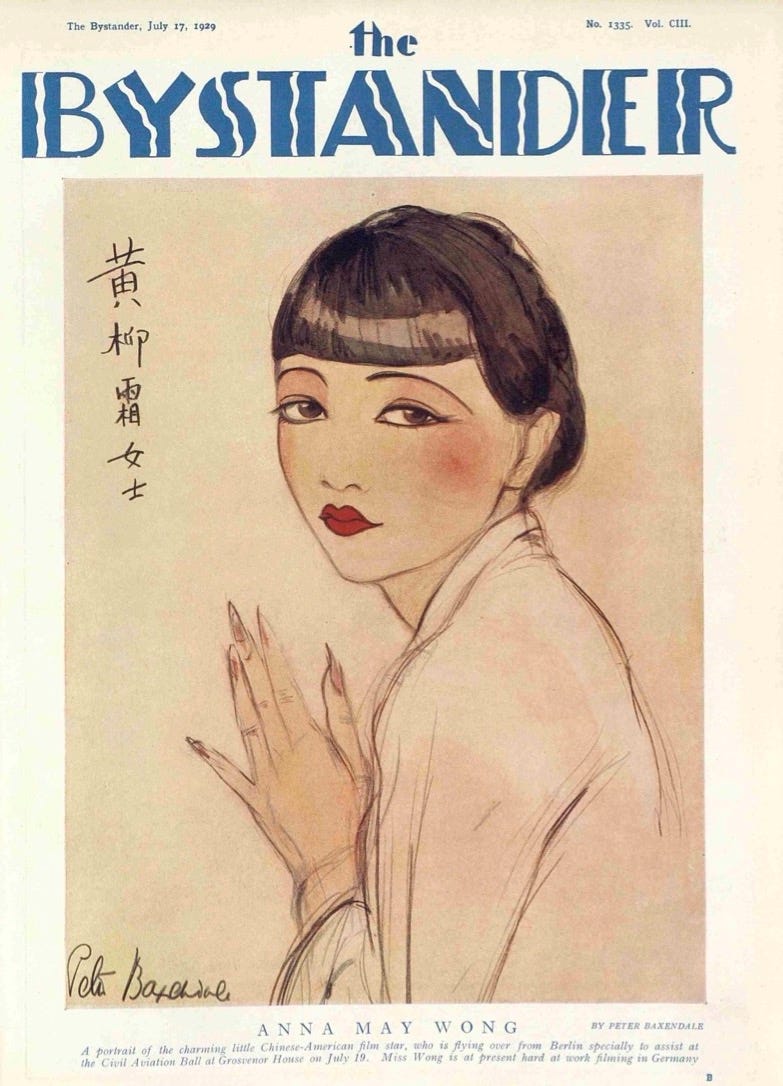

Amy Beatrice Baxendale was an English artist who went by the name Peter Baxendale. Though she was particularly interested in sketching scenes from the world of the circus, she also excelled at portraits and made studies of several famous people, one of whom was Anna May Wong. Baxendale’s portrait landed on the cover of Bystander, a popular weekly tabloid that regularly reported on AMW’s goings on about town.

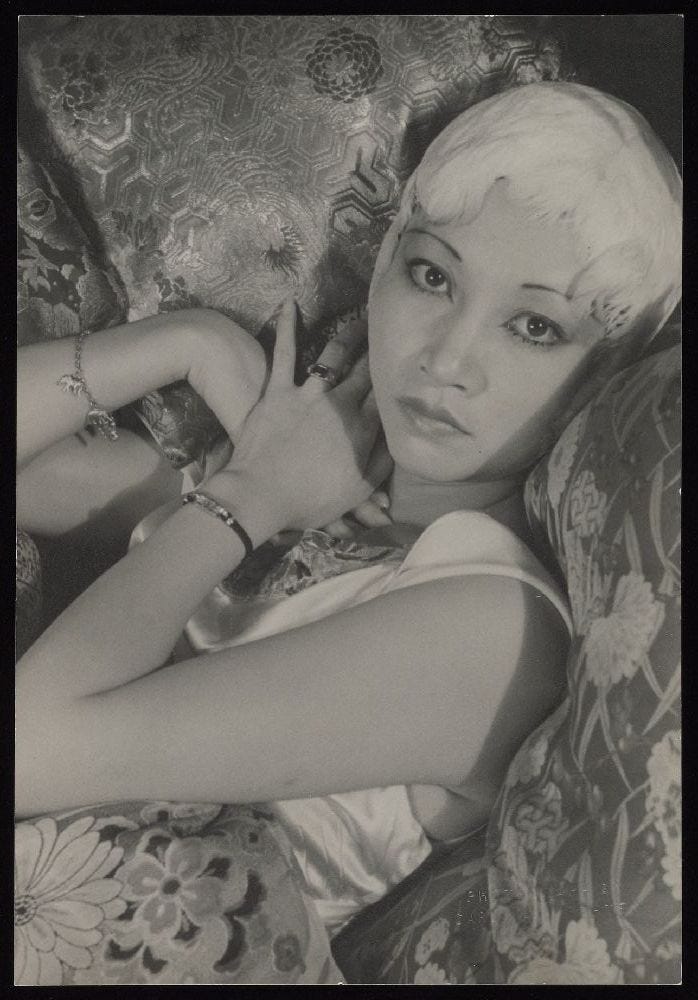

Anna May first met Carl Van Vechten, the successful American novelist and critic, while she was in London in 1929. Carl was on vacation with his wife, the Russian actress Fania Marinoff, and soon to begin work on his final novel, Parties, a sendup of the boozy, aimless 1920s. Then came the Great Crash and many fortunes with it. Critics didn’t find Carl’s satire quite so funny anymore. Realizing that his writing career was pretty much finished, he decided to embark on a career as a photographer. In the spring of 1932, while Anna May was based in NYC for various vaudeville engagements and personal appearances, Carl invited her to sit for him as his first official portrait subject. I imagine they had a grand time improvising different looks for the camera with all the props, frocks, and backdrops at their disposal. The session included a series of AMW wearing a top hat and drinking from a coupe, but for whatever reason, she didn’t like these particular pictures of her in menswear. One of the photos she did like, though, was this striking portrait of her in a white feathered wig. There is something about it that feels so modern. It always seems to me like it could have been taken yesterday. Carl Van Vechten would photograph AMW many more times in the succeeding decades and become well known for his portraits of influential figures in the Harlem Renaissance. The two remained friends and kept up a lively correspondence until the end of AMW’s life.

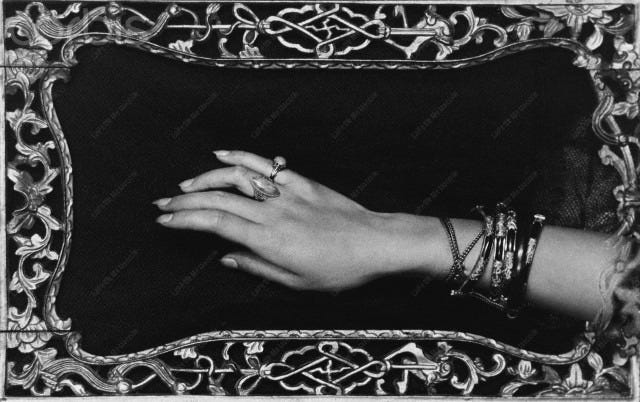

Although E.O. Hoppé, the German-born photographer, made many lovely portraits of Anna May during the early days of her career in the mid-1920s, I’m most fascinated by his studies of her hands. Around this time, AMW had started to cultivate her image as an exotic, Asian beauty, and to set herself apart, she wore her nails long and filed to a fine point (almost like claws). Sometimes she even dressed her fingers in metallic, jeweled nail guards, similar to those of the Dowager Empress. Everywhere she went, people never failed to comment on her unusual manicure and how it reflected her essential Oriental soul. To Anna May, though, it was merely another tactic—like her signature bangs or her British-tinged accent—to distinguish her celebrity from other stars in Hollywood.

You can’t get any more Classic Hollywood than this shot of AMW by George Hurrell. Considered the “master of Hollywood glamour,” he got his start when a mutual friend suggested him to photograph actor Ramon Novarro of Ben Hur fame. The pictures turned out wonderfully, and the rest, as they say, is history. MGM hired him at the beginning of the 1930s and Hurrell later opened his own studio on Sunset Boulevard. Throughout the 1930s and 40s, he shot stylized portraits of countless movie stars like Myrna Loy, Jean Harlow, Norma Shearer, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Joan Crawford, Katherine Hepburn, and many more. Like this portrait of AMW, his photos often utilized the same dramatic low-key lighting that became emblematic of film noirs. They were sexy too. He made a second portrait of Anna May that is quite risqué.

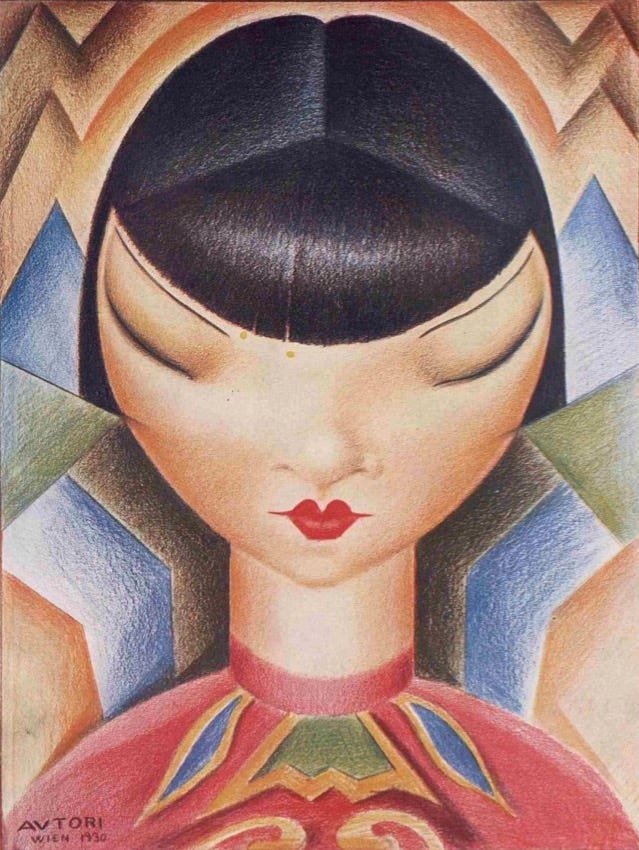

Outlandish, distorted, almost Cubist, Autori’s portrait of AMW is one of her most memorable. The man behind the name Autori, Fernando Autori, was an Italian opera singer and artist from Sicily. Below his signature on the artwork he includes the time and place where it was created: Vienna 1930. Autori most likely drew AMW while she was in Vienna starring in the operetta Tschun Tschi.

I’m invariably intrigued when I see a photo like this one that has been taken with as minimal a light source as possible. It’s almost like seeing with the human eye in a dark, pitch-black room. Anna May appears like an apparition. And yet the light that is available reveals such subtle shades of gray and black. Her figure is still perfectly legible. And the exquisite detail of her delicate fingers draped over the divan! Francis Goodman, a London-born photographer of German ancestry, had some real skills. He took this and several other portraits on AMW’s return to London in 1933.

To my eye, Cecil Beaton’s photography has a whimsical, imaginative, over-the-top sensibility to it. Maybe that’s why Vogue employed him for three decades. This portrait of AMW in particular has a wow-factor that never gets old. The flowers hanging down and all about her. The soft, magical glow from above. The white dress and the bunches clasped to her bosom. The scene evokes an aura of innocence. Beaton knew how to accentuate Anna May’s ethereal beauty. It almost looks like it could be a bridal picture, except that AMW never married. Beaton was part of an aristocratic set of artists, writers, musicians, and socialites called the Bright Young Things, and Anna May became a friend and frequent guest at many of their social outings during her time in London.

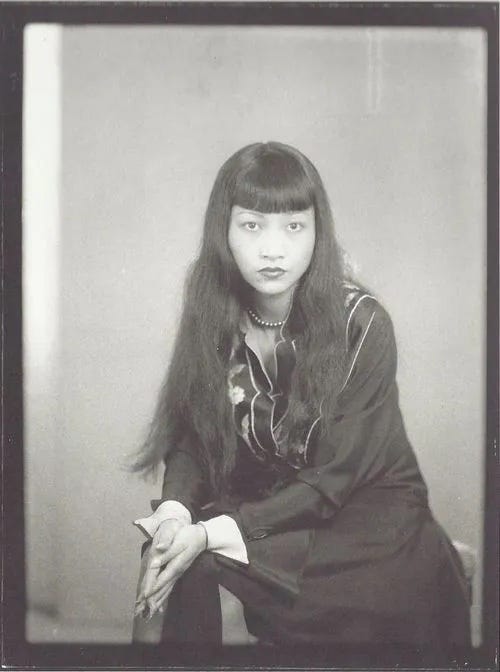

May Ray was an American artist who became a prominent figure in the Dada and Surrealist movements. The Museum of Modern Art states that, “Dada artists shared a profound disillusionment with traditional modes of art making and often turned instead to experimentations with chance and spontaneity.” That intent certainly feels apropos here. Man Ray defected to Paris in 1921 and spent nearly two decades there experimenting with different kinds of image-making, including portrait photography. What I like about this portrait is how candid and serious it feels. Anna May peers directly into the camera lens, expressionless. Besides her silk dress and a single strand of pearls around her neck, she is unadorned. Her hair is let down to its full length and hasn’t been styled. There is no artifice to her appearance or in how she is posed. It’s an honest portrait, like this is the real Anna May Wong when no one is looking (though of course we still are).

Edward Steichen was an important figure in the history of photography and in the New York art scene in the early 20th century. His photographs appeared in Alfred Stieglitz’s journal Camera Work, the same publication where Sadakichi Hartmann wrote some of the first photography criticism. Together, Steichen and Stieglitz established the influential gallery at 291. His portrait of AMW was likely made while she was in New York doing her successful run on Broadway in On the Spot. I have a clear memory of seeing this photo hanging in the MOMA in NYC and gazing at my reflection in its inky black depths. I could probably look at this photo forever and continually find new aspects to it, new meanings. Anna May Wong, a disembodied head, a larger-than-life face on the screen, just another object placed on a table next to a giant pom-pom chrysanthemum. Is the flower, an obvious piece of Chinoiserie, meant to reinforce her Asian exterior or to complicate it?

Updates in Brief

Last month Karen Mok, COO and co-founder of The Cosmos, interviewed me about my book on Anna May Wong for The Care Package newsletter. We had an engaging conversation on how much Hollywood has changed since AMW’s day and why I’m adamant about not characterizing her life as a tragedy. Read the full interview here.

Some of you may be familiar with my photojournalism project about Chinese restaurant workers in New York. In 2018, I adapted the project into a photo exhibition called Thank You Enjoy. Now that in-person gallery visits are possible again, the show is opening in Austin, Texas. The photos and stories will be on display at the Asian American Resource Center in Austin until September. If you’re a Texas local, stop by and check it out! Details here.

To mark the end of AAPI Heritage Month, I helped co-write an op-ed in The Stanford Daily as part of a collaborative, multi-generational coalition of Stanford alumni and community members. The piece publicizes the contributions of Asian Americans to Stanford's legacy and demands that the University open up dialogue with community stakeholders. If you’re on Twitter, please consider retweeting it in solidarity!

Very nice detailed coverage. Most thorough. Excellent photos. Book will be a keeper.

MAN RAY! great collection of photos Katie. I do sort of love that first one with the lillies too.