During senior year of college there was one task that dogged me persistently: writing my honors thesis. Every time I hung out with friends or went for a long winding drive on the backroads around campus, a momentary thought of the thing I was supposed to be doing would inevitably flit across my mind and pangs of anxiety and panic would resume gnawing at my nerves.

In what I thought was a brilliant and cheeky move, I took a piece of blank printer paper and wrote on it in block letters, “What is your thesis?” I taped my DIY-sign to the wall directly above my desk where I would be forced to look at it morning, noon, and night. Within a week I stared past it completely, as if I’d forgotten how to read, because that’s how procrastination works. (You know when something’s not a priority because every week it moves up the to-do list yet somehow it never gets done.)

I was hopelessly lost. I had no idea what a good thesis should be or how to write one. The administrator in my department liked to recite a piece of advice whenever one of the beleaguered seniors happened into the office: “Don’t get it right, get it written.” Every fiber in my being balked at that statement. I kept turning her words over in my head. What’s the point of writing something if you don’t get it right?

In the end, my thesis got written when it finally had to—in the last two weeks of senior year. Those sixty pages of double-spaced text were unequivocally the longest thing I had ever written. More important, it provided me with a space to explore and germinate the idea of writing a full-length book about Anna May Wong; my thesis was titled “Imagining China: American Perceptions of the Chinese through 1930s Cinema.” Still, I wouldn’t say I got it right.

Fourteen years later, I like to think I have a much more experienced view on the matter of writing. I’ve spent most of my adult life as a book editor, first in-house at HarperCollins and Amazon, and then working independently with private clients. A common refrain among first-time authors has frequently been, Am I doing this right? I have no idea how to write a book. The truth is nobody really knows how to write a book. How could you? Because if you fully understood the immensity of the undertaking you’ve signed yourself up for, comprehended that it will eat up years of your life, give you heart palpitations in the middle of the night when you can’t sleep, you’d probably think better of it and decide not to bother after all.

I’ve always known that writing a book is objectively hard and I think most people share that opinion, which is perhaps why “the book” remains a revered institution despite the fact that people hardly read them anymore (sorry, that’s the cynical publishing veteran in me). But theoretical knowledge—knowing something is difficult because you’ve been told it’s so—and the wisdom of experience—knowing something because you’ve done it, you’ve struggled and maybe failed—are two separate things.

After years of guiding others through the book-writing process, of ghostwriting, re-writing, and publishing some of my own work, I have come to see the prudence of that college administrator’s pithy advice. I’ve internalized it and repeated it to other writers. Winston Churchill said it in his own way, “Perfection is the enemy of progress.” This is how I trick myself into sitting down in front of the blank page, cursor blinking. I write knowing that the words rarely come out right on the first try. They won’t be as grand as what I’ve envisioned in my head, but there will be time for fixing all of that as long as I get the words down first.

At the beginning of 2020, my proposal for a book about Anna May Wong sold to Dutton Books. In the year that I’ve been working on it, I’ve written 25,000 words, which feels really good, but at the same time, it’s too early to celebrate because I’ve still got three-fourths of the way left to go.

Here’s where we get to the real challenge of writing a narrative nonfiction book about the life and times of Anna May Wong. Writing is hard, researching is harder. It’s an endurance game. Let me explain what I mean.

Narrative nonfiction or creative nonfiction is a kind of storytelling that is rooted in fact but written to read like fiction. In my case, written to read like a biopic. Of course, there are things that will forever remain unknowable about AMW since she has been gone from this earth for sixty years. But she left behind plenty of bread crumbs for us to follow. As a writer, it’s my job to connect the dots and tell you what those bread crumbs mean. Anyone can inventory the facts of her life—and I’m glad that more publications, platforms, and podcasts like Google, TIME, and Mobituaries are doing so to raise her profile for a public that has forgotten she ever existed—but a book has to dig deeper.

On Slate’s How To! podcast, Taffy Brodesser-Akner talked to Charles Duhigg about how she wrote her novel Fleishman Is in Trouble* and shared this gem she learned from Jonathan Franzen:

Jonathan Franzen once said a lot of people think a book is about what happened, but the better version of a book is, “Here’s what happened. Now let me tell you how.” And I thought that was so remarkable because it means that you don’t have to have some big reveal about action. You have to have a big reveal about character. And the process of writing is very much the process of getting to know your characters.

This holds true for narrative nonfiction too. In order to know AMW and to be able to write her as a character, I have to find a way to inhabit her world. I’ve read biographies and memoirs of her contemporaries and the big names that influenced her career like Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, James Wong Howe, Gloria Swanson, Marshall Neilan, and Pearl Buck. I have many more still to read: Sessue Hayakawa, Paul Robeson, Josephine Baker, Carl Van Vechten, Eric Maschwitz. I’ve learned about Eadweard Muybridge and the photographic studies he produced for Leland Stanford that led to the invention of the motion picture. I’ve studied the frontier thesis, Chinese American history, California during the Gold Rush, and the emergence of Los Angeles, a city in a desert where a city never should have been. I’ve revisited Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose early novels immortalized the Jazz Age, the same era in which AMW got her first taste of stardom as the Chinese flapper.

I’ve spent days, weeks even, combing through newspapers and movie magazines for interviews with AMW, announcements of films she was cast in, notes on parties she attended and international travel plans. The Los Angeles Times archives alone yield thousands of results for the keyword “Anna May Wong.” No mention is too slight because you never know what detail may end up being the key to unlocking a specific moment in her life. Thank god for digitized archives. Not too long ago I would have had to read through decades of microfilm rolls just to see whether AMW happened to be mentioned.

I collect AMW minutiae like the bric-a-brac that line a hoarder’s shelves. For example, I know a lot of little details like the following:

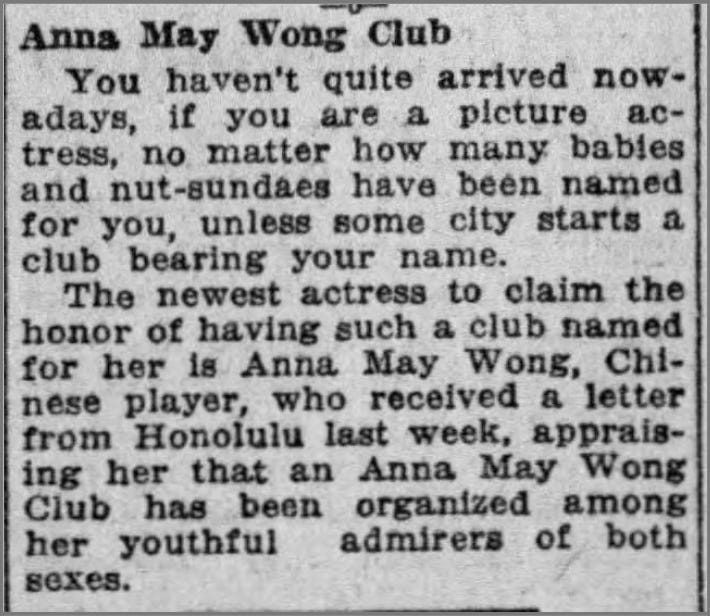

In September 1923, a group of youthful admirers in Honolulu formed the first ever Anna May Wong Club (h/t Mel Guo).

When Buddy Rogers, Mary Pickford’s beau, made his debut as the orchestra leader at the Pennsylvania Hotel grill in NYC the summer of 1932, Anna May was one of the many Hollywood celebrities in attendance.

The Los Angeles Times reported that on May 26, 1924, a young man named Gage Wong, “brother of Anna May Wong, motion-picture actress,” was given a speeding ticket in the amount of $28. None of AMW’s brothers were named Gage; perhaps this other Wong thought it might help him get out of the fine if he claimed a famous sibling.

In another LAT item, AMW shows up in court to defend James Norman Wong, one of her actual brothers, on the charge of “illegal sale, possession and transportation of fireworks” on the Fourth of July.

Will I use all of these quotidian yet interesting-all-the-same tidbits in the book? Probably not, but culling them into something that resembles a life and tells a story is part of the journey of writing a book.

One advantage is that I’m picking up where others have left off. Books on AMW by Graham Russell Gao Hodges, Shirley Jennifer Lim, and Anthony B. Chan have given me an important and essential roadmap to known resources on AMW.* When I read and re-read their books I am constantly asking myself, How do they know that? I spend a lot of time going through other authors’ citations, which let me tell you, can be a real pain in the ass. Endnotes tend to be idiosyncratic, a jumble of sources formatted willy-nilly, volume and issue numbers included at random but never consistently, and typos that can send you down a rabbit hole for hours at a time.

Ultimately, I have to look beyond other people’s endnotes. I’m not here to rehash what’s already been printed. Instead, it is incumbent on me to pay attention to all that they might have missed. The problem then, clearly, is not that there isn’t enough material out there to mine from AMW’s life. I haven’t even mentioned the FBI files, immigration records, or the thirty years of correspondence between her and Carl Van Vechten sitting on my hard drive. There’s so much out there the trick is knowing when to stop.

Getting lost in the back matter is a peculiar kind of writer’s hell, but there is joy in the sleuthing process, and disappointments too. Being able to luxuriate in another woman’s glamorous life during a global pandemic has been a welcome indulgence and escape. But I know that every day I spend deep in the weeds of research is another day I’m not writing new pages for the book. This is the essential tension I’m grappling with now, figuring out when I know enough to get back to writing the next chapter. Because in the back of my head there is a voice reminding me: Don’t get it right, get it written.

So if you ask me how the book is going, this is my meandering 1800-word answer. In other words, I’m right where I need to be—I think. Any and all encouragement is appreciated, especially in the form of one-line aphorisms.