Enter the Dragon

Lunar New Year 2024, book tour dates, plus a sneak peak inside Not Your China Doll

恭喜发财!Or as Anna May Wong would say, gung hei fat choy! This weekend marks the start of Lunar New Year 2024, an extra special year because it’s the Year of the Dragon.

Throughout her career, Anna May was often associated with the dragon—whether in the Fu Manchu flick Daughter of the Dragon, the stereotypical roles she often had to play as a so-called “Dragon Lady,” and in some of her most memorable outfits, like the dress she wore in Limehouse Blues with a large sequined dragon. Though the symbolic meaning of dragons has often been interpreted differently by Western audiences, usually with a sinister edge, Anna May’s association with this magical creature is actually quite fitting. For Anna May Wong herself was born in the Year of the Dragon, just like another Chinese American icon, Bruce Lee.

Dragons are perhaps the most mystical creatures in Chinese mythology. Writer Alice Sparkly Kat describes them as “weird chimeras,” hybrids with features borrowed from other animals: “a camel’s head, deer antlers, snake bodies, carp scales, clam bellies, cat eyes, eagle hands, and tiger paw pads.” Unlike dragons in medieval Europe, which were imagined as fire-breathing lizards with wings, Chinese dragons are primarily associated with water—gods of the oceans who provide rain for the harvest and safe passage to those crossing the sea.

Bruce Lee famously said “be like water.” Formlessness, the essence of water, can been seen as an advantage because it allows one to be endlessly resilient and adaptable. AMW also represented this ethos through her ability to reinvent herself in every decade. As I write in the book: “She was like a fast-moving river flowing effortlessly through the cracks, around rocks and fallen logs, and over cliffs until she arrived at her destination, a great lake, placid and calm to the casual observer but continually churning beneath the surface. Everywhere she went, she changed the landscape, her obdurate sense of purpose carving through rock like steadily dripping water, breaking down centuries of sediment slowly but surely.”

According to the Chinese zodiac, dragons “embody a magnetic blend of ambition, confidence, and charisma.” All words that describe AMW to a tee. This year is the Wood Dragon, which also happens to be AMW’s precise zodiac sign. “The element of wood is seen in Daoist tradition as a return to the natural state of being.” Thus, the Wood Dragon “beckons us to explore our depths, fostering curiosity, independence, and a thirst for knowledge.”

This is all to say, 2024 is Anna May Wong’s year like no other. It makes perfect sense to me that her life and legacy have been steadily revived in the years leading up to this moment and that Not Your China Doll, my biography of AMW, is coming out on this most auspicious year. All the more reason to embrace this season of change. Happy Year of the Dragon!

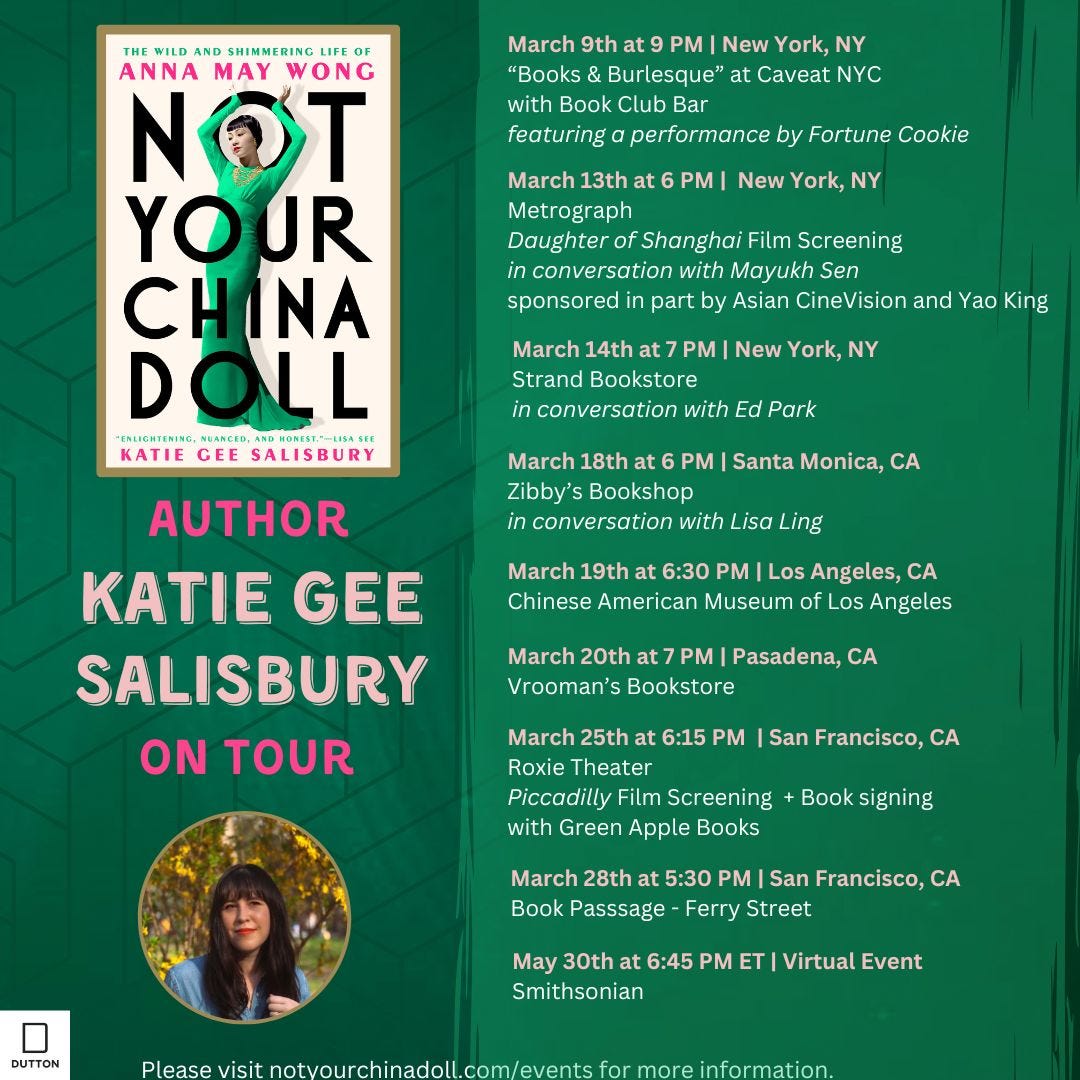

In book related news, I’m excited to announce my preliminary book tour dates! If you’re in the New York area, I hope you’ll join me for a very special launch party at the Red Pavilion in Bushwick on March 12. For one night only, we're reimagining Anna May Wong's jazz age bungalow. The evening’s activities will include a reading from Not Your China Doll by yours truly, book signing, tarot readings by Helen, era-appropriate tunes by DJ YiuYiu 瑶瑶 of Chinatown Records, and tea served by Tea Arts & Culture. Reserve your ticket here. You can buy a copy of the book at the event or bring a preordered copy with you and I’ll happily sign it.

I’ve also got a killer lineup of events in NYC (Books & Burlesque, a screening at the Metrograph, The Strand Bookstore), Los Angeles (Zibby’s Bookshop with Lisa Ling, Chinese American Museum of Los Angeles, Vroman’s), and San Francisco (a screening at the Roxie, Book Passage), with more dates and cities to come soon. For the full roster of events and links to rsvp, visit notyourchinadoll.com/events. I hope to meet many of you IRL over the next few months!

Finally, as a special treat for all my loyal Substack readers, I’m sharing an exclusive excerpt from Not Your China Doll. And it’s perfectly on theme for the Lunar New Year. Enjoy!

Chapter 4: Year of the Flapper

For 364 days out of the year, the shopkeepers, butchers, laundrymen, and cooks of Chinatown worked tirelessly at their trades, serving their community as well as the thrill-seeking gweilo who passed through on a “slumming” tour or turned up for a bowl of chop suey and a few souvenir trinkets. But come Lunar New Year, the faithful worker finally abandoned his post. The shopkeeper shuttered his storefront, the butcher hung up his bloodied apron, the laundryman turned a blind eye to the soiled shirts piling up, and the cook snuck off on his break, the first of many, to join his fellow Chinese Americans in celebrating the start of a new year.

Lunar New Year 1927 saw the streets of Los Angeles Chinatown filled with revelers: aunties and uncles dressed in their Chinese best, young married couples in smart-looking suits and dresses, some with babies in tow, and even the tired old bachelors who could hardly believe the Western frontier town they helped found had sprouted into a modern metropolis all these years later. Strings of flags and paper lanterns decorated the streets from above, while boxes of fresh lychee nuts and candied fruits beckoned from store windows. There was no want of entertainment, what with the rat-a-tat-tat of firecrackers flashing in alleyways and confetti bombs coating everyone and everything like a sheet of colorful snow.

The only things that could part the great sea of people were the competing lion dance troupes, whose chants and pounding drums heralded the arrival of the lion. Decked out in brightly hued red, gold, and orange fringe, the mystical lion and his bushy mane zigzagged through the crowd. Two men manipulated the lion’s every move from underneath, cloaked in the beast’s festive hide. In the middle of its boisterous dance meant to chase the evil spirits away, the lion pulled up to an unsuspecting spectator or a shopkeeper watching from a doorway and, with eyes blinking and mouth ajar, waited for an offering. According to tradition, one must feed the beast in exchange for good fortune by tossing coins wrapped in red paper or a fresh piece of produce into the creature’s gaping mouth. The latter oblation is then unceremoniously gobbled up and shreds of cabbage leaves regurgitated into the air. The rush of excitement one got from this ritual never waned, whether it was your first Lunar New Year or your fiftieth.

As the festival carried on, upstairs, tucked away in one of Chinatown’s cafés, another kind of celebration was underway. Anna May Wong and friends Moon Kwan and Jimmy Wong Howe had banded together to usher in the Year of the Rabbit with a lavish fete for all their Hollywood friends. “I shall never forget Chinese New Year’s of 1927,” Hollywood reporter Harry Carr, one of the trio’s guests, declared in his column for the Los Angeles Times.

Chopsticks were passed around the table and the uninitiated given a quick lesson in how to use them. Anna May then instructed her guests how to say “Gong hei fat choy!” with feeling. Waiters in loose-fitting black jackets and trousers stacked the table with dishes of rice cakes and dumplings, steamed fish and candied ginger, and the most unusual delicacy of them all: bird’s nest soup. The fifteen-course banquet transitioned seamlessly from one course to the next, likely through many rounds of jasmine tea and bathtub gin, coming at last to a final, filling dish, such as longevity noodles to encourage a long and fruitful life.

“Jimmy raises English bulldogs and shoots craps; Anna May Wong is a flapper of the flappers, and a great belle; Moon Qwan is an up-to-date young journalist,” Carr explained, tendering his hosts’ American credentials. “But down in that dim old cafe—digging into strange and exotic foods with our chopsticks, they all slipped out of the jazz age as one takes off a coat. And were Chinese again.”

This idea that being Chinese and American was a contradiction in terms had been weighing on Anna May ever since she was thrust into the limelight. It was as if the rest of America’s populace had conveniently forgotten their families had once called foreign shores home too. Indeed, her race had become the central refrain of every press piece and interview she did. Rudyard Kipling’s famous line of poetry—“Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet”—was quoted so often in articles about her, perhaps she was beginning to wonder whether she also deserved a cut of the royalties that were certainly due to him.

People formed preconceived notions about her based on looks alone. She’d learned to steel herself against the suspicious and condescending stares that seemed to follow her everywhere. Secretly, she hated the way people judged her. They saw a Chinese girl and intuited she must be foreign, primitive, and unfeeling—when she felt that she was something else entirely. What did they know about her true nature, anyway? Winning the attention of reporters and gossip columnists was her chance to set the record straight, or so she thought.

Anna May took great pleasure in subverting her interviewers’ expectations, and she worked hard at it too. The indelible icon of the Roaring Twenties was the flapper, a persona Anna May embraced wholeheartedly. But she wasn’t just any flapper. She was queen of them all. Dressed to the nines in “a tiptilted hat, pure Parisian heels, sheer silk stockings, and a Persian lamb wrap,” she talked circles around journalists in her jazz girl jargon, and waxed poetic about her sky-high career ambitions as a new woman. She made damned well certain they saw she was no shrinking lotus, but everything one had come to expect of an American “It” girl. “She’s never been to China,” they would invariably spout. Somehow, they didn’t think to mention Anna May had never been to Paris either.

The strategy had worked so well, her reputation as the “Chinese flapper” now preceded her. Her independent streak had also led to not a few arguments at home with Wong Sam Sing and looming threats that he would marry her off to the next eligible suitor. Some in Hollywood questioned why she continued living at home when, with her movie star salary, she could easily afford to get a place of her own. Caught between the expectations of her Hollywood friends and her traditional Chinese father, she wavered with indecision. The last couple of years had seen her move in and out of the laundry on Figueroa Street several times, alternately despising the hectic workplace and its cramped quarters, and then, once alone in her lifeless flat, desperately missing her brothers and sisters and the family meals they regularly shared together.

“Anna May Wong cannot make up her mind as to her residence,” Photoplay complained. “She moves from Hollywood to Chinatown and back again at regular intervals. . . . Anna is our leading Chinese star. Likewise, she is one of the brightest of our flappers.”

By the fall of 1926, though she had not completely made peace with it, Anna May had come to an understanding of her identity and of her position in America’s racial politics. For years the media had editorialized their encounters with her, selectively quoted certain comments over others, and emphasized aspects of herself that somehow read sensationally to fans when they

seemed perfectly ordinary to her. All this talk about her flapper image had made her realize that it wasn’t truly her: it was an act. Like any other part she’d played in the movies, she’d donned the persona when it suited her, which meant she could also drop it.

It was time for the public to hear her story unfiltered, in her own words. In a two-part commentary in the pages of Pictures, she set to work right away on dispelling the most pernicious misconceptions about her.

“A lot of people, when they first meet me, are surprised that I speak and write English without difficulty. But why shouldn’t I?” Anna May began. “I was born right here in Los Angeles and went to the public schools here. I speak English without any accent at all. But my parents complain the same cannot be said of my Chinese. . . .

“I’ll explain as best I can,” she continued, “how it feels to be an American-born Chinese girl—proud of her parents and of her race, yet so thoroughly Americanized as to demand independence, a career, a life of her own.”

She told readers the story of how her grandparents came to the United States seeking gold; how her father was born in California and worked hard to earn enough money to marry and buy land in China; how her maternal grandparents submitted a picture of her mother to a Chinese matchmaker in San Francisco and subsequently married their daughter to her father as his second wife at the age of fourteen. “Chinese men have it all over the rest of us,” she added, explaining their right to wed as many wives as they desire. For Chinese women, marriage was not necessarily a cause for celebration but a matter of course. Thus, the bride wept on her wedding day.

“You can see that the Chinese woman’s life is not a particularly enviable one. She is considered far beneath the male members of her household, and is a servant to them. I just [don’t] see myself being let in for anything like that!”

Anna May spoke candidly of the moment she first realized the way others saw her—when the boys and girls at school taunted her for being Chinese—and of her education in the differing expectations of American and Chinese cultures. She recalled wryly not having any compunction about skipping class to make her way onto movie sets; she endured the whippings that followed rather stoically.

She complained of the familial hierarchy created by her father’s two marriages. His first wife, who bore him a son, remained “first” in every sense of the word. Wong Sam Sing faithfully forwarded money to her despite not having been back to China in nearly thirty years. Meanwhile, his son, Wong Tou Nan, was not only the first child but, as the eldest son, was considered next in line to be the family patriarch. Wong Tou Nan and his mother regularly sent missives from China to the Wong clan in Los Angeles directing them on how to order their lives. And yet, when Wong Sam Sing sent his son and first wife a clipping of Anna May modeling a mink coat in the paper, Tou Nan wrote back self-servingly, “Tsong is indeed very beautiful but please send me the dollar watch on the back of the picture.” Anna May firmly put her foot down when her father suggested she send some of her own earnings to her half brother in China, who at thirty-six years old already had a family of his own that was in large part supported by theirs.

“But, though I love father dearly, and am proud of my people, I can see their faults. It is the cause of much conflict in me, sometimes. I don’t suppose an American girl can begin to realize that conflict. . . .”

In previous interviews, Anna May had sometimes turned philosophical. Occasionally, she might probe her interviewers for answers to some opaque problem she was working out in her head. “Say, do you ever wonder what life’s all about, anyway?” she once asked Helen Carlisle. Here, most tellingly, she put into words the thing that had caused her so much consternation and soul-searching.

“Do not think it is easy for me to throw over the traditions and customs of my people. I have behind me countless centuries of Chinese ancestors who have unquestioningly obeyed the rules laid down for them by their ancestors. No people revere their parents as do the Chinese. The father’s word is law in the household, never to be disputed. The Chinese child is born with ages of superstitious belief traditions in his blood. It is no light thing to cast them all aside, in one generation, believe me. Sometimes when I have defied my father, who is the kindest, gentlest man alive, I have gone off by myself and wondered if, after all, I was in the right. I have wondered where my course will lead me.”

The conflict was not the fact of her being both Chinese and American. The two sides of her identity were not at war with one another. No, the contradiction was in others’ insistence that she be one thing or another, that she live up to their expectations in lieu of the ones she had clearly set for herself.

“I just tried to explain to [my mother] that my life must be lived along different lines than hers had been. It might not be a happier life, but that was for time to tell.”

She said it plainly and unequivocally to the world: “It is my life.”

At the same time, Anna May had tried so hard to fit in and be like the other girls, she nearly lost herself in the process. But now she had finally registered what it meant to be Chinese American; the script for that role didn’t yet exist, so she was free to write it herself.

The Lunar New Year of 1927 brought with it an opportunity to turn over a new leaf. The flapper joke had grown stale and the hedonistic euphoria that had fueled the decade-long party they called the Jazz Age was wearing thin. Anna May was ready to hang up her cloche hat and slip dress. Sensing this and wanting to resolve the discord that had come between them, Wong Sam Sing extended an olive branch to his daughter: “Anna May, if you will come home, I will build you a house which shall be all your own.”

Anna May returned home with equanimity, knowing that it was exactly where she was meant to be. “I had my fling in Hollywood,” she told her old friend Rob Wagner. “After my first big success as the Mongolian slave girl in The Thief of Bagdad I thought living there the thing to do. The publicity men were doing their best to Americanize me and I appreciated it, for I am an American: also I appreciated the confidence placed in me by my father when he allowed me to leave home, a very hard thing for a Chinese father to do. I employed a sort of governess who tried to make an American ‘lady’ of me but all the time she was instructing me I could hardly keep from saying: ‘Be yourself, madam: be yourself!’

“In fact I grew to think there was no use in learning to act, for in Hollywood everybody was acting,” Anna May reflected. “Even the houses seemed artificial and finally I began to feel that I was dwelling within a world of ‘sets.’ Then I decided to go back to the laundry and to my family, where I would hear the truth!”